Gene therapies’ moment of reckoning

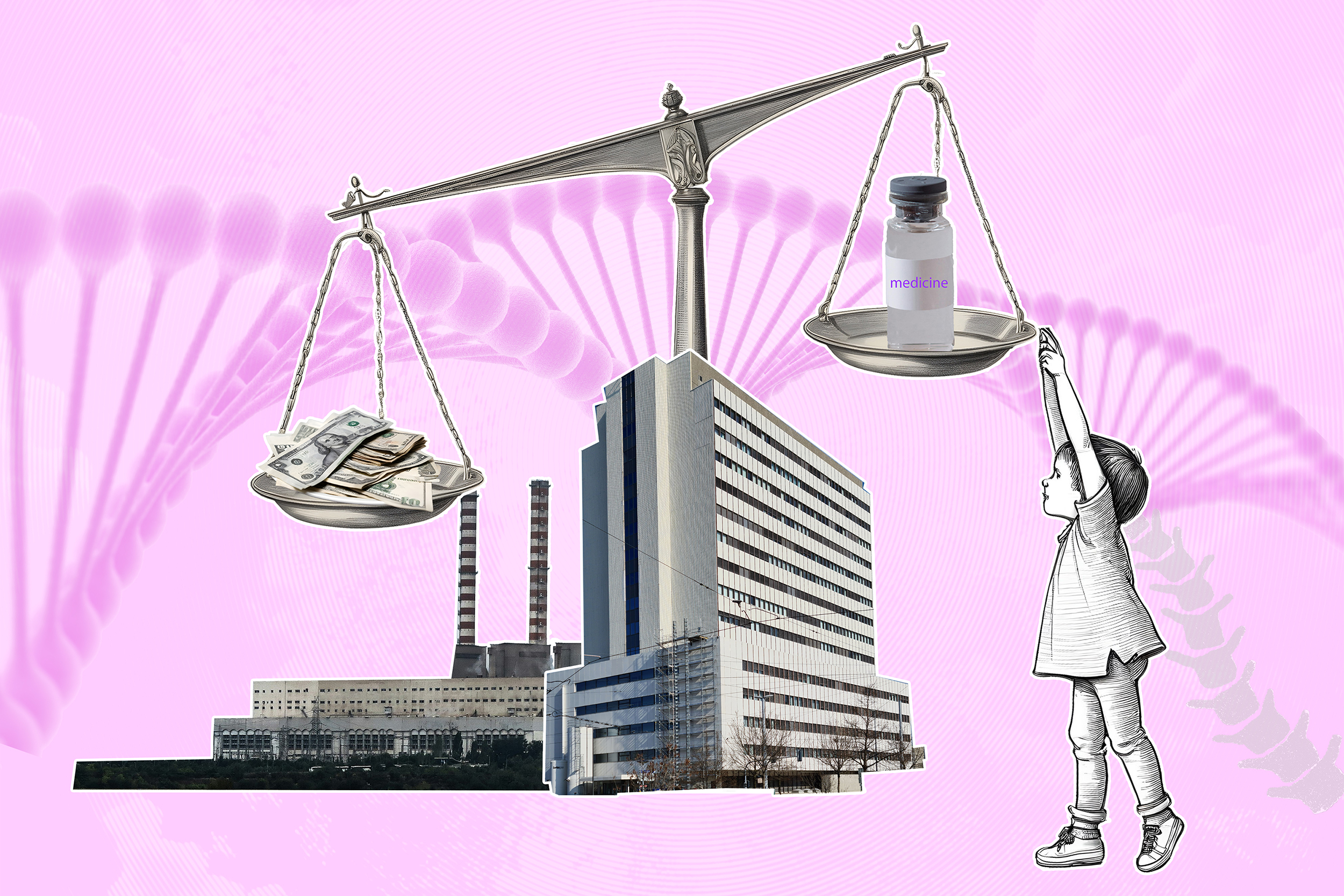

Gene therapies are a revolution in medicine but over the past few years, companies developing them for many serious hereditary diseases have faced various setbacks. What will it take for gene therapies to fulfill their promise?

Five years ago, gene therapy companies were flush with money. InvestmentsExternal link in cell and gene therapy topped $19.9 billion (CHF17.6 billion) globally in 2020, double the $9.8 billion raised from public offerings, venture capital and other financing in 2019.

Today, the industry looks different. Safety concerns, sceptical patients, hefty price tags and a host of manufacturing challenges have humbled the field. In 2022 and 2023 investments dropped below $13 billion, improving slightly in 2024 after some positive approvals and an uptick in clinical trials in Europe.

In the face of a cash crunch, some small gene therapy makers, once investor darlings, have slashed workforcesExternal link, collapsed, or abandoned markets entirely. This has prompted media reports of a crisisExternal link in the gene therapy industry.

“When one drug does well, people think that we’ve already won, that we’ve figured it out,” said Rodolphe Renac, an expert in healthcare innovation and president of the US affiliate of consulting company Alcimed. “Despite remarkable outcomes from some gene therapies, there are still improvements needed.”

Swiss companies like Roche and Novartis continue to invest in the field, and scientists remain optimistic about gene therapies’ promise to cure diseases. But the tough reality of getting them to patients has led to mounting calls for changes to the way gene therapies are priced, paid for, and communicated to the public.

Cell and gene therapies are often grouped together because they are both treatments that aim to treat, prevent, or even cure diseases by modifying processes at the cellular or genetic level. Cell therapy introduces cells (that may be genetically altered) into a patient’s body to restore function or fight disease.

In gene therapy, a functional gene is introduced or a faulty gene is corrected to restore normal cellular function. For gene addition or replacement, many therapies use a viral vector to transport genetic material into cells. Crispr-Cas9 is a technology used for gene editing.

Capturing the real costs

Gene therapies are widely considered a paradigm shift in medicine. By modifying or replacing genes or altering gene expression, often with a single infusion, gene therapies offer the prospect of not just treating but actually curing deadly hereditary diseases.

One of the biggest hurdles facing gene therapies, though, is how to price and pay for one-time “cures”. In January, the gene therapy Hemgenix sold by US firm CSL Behring for haemophilia B became the most expensive single therapy reimbursed by health insurers in Switzerland at CHF2.7 million ($3 million).

Most gene therapies on the market are for rare diseases – those that affect a small portion of the population (in some countries 1 in 2,000 people). Companies argue that the high price tags, often in the millions per patient, are needed to make up for the small volumes.

As more gene therapies are launched, payers, including both private insurers and national health authorities, are becoming more concerned about their ability to pay for them. Some payers, particularly in Europe and Latin America, have pushed backExternal link on the price tags, in some cases denying coverage entirely or negotiating the price downwards.

More

Turkey vs. Zolgensma: the battle over a $2.1 million drug

Even after securing US approval for three gene therapies, Boston-based company Bluebird Bio withdrew from the European market after struggling to secure reimbursement agreements with European governments. The three therapies were priced in the US at $2.8-$3.1 million per patient.

“I think the market is now clear that a one-time multi-million-dollar payment for a one-shot therapy simply is not going to work,” said Daniel Parle, a drug contracting consultant at Lyfegen, a Basel-based global provider of drug-pricing management solutions, in an email.

Drugmakers argue that a gene therapy will not only save lives but spare families and health systems a lifetime of costly treatment. However, “it’s still difficult to measure the true value of a gene therapy with different decision makers, budgets and expenditure tracking systems”, Parle said.

This value also has to take into account the fact that gene therapies often require multiple screening tests, a controlled infusion setting, and close monitoring by specially trained staff, which all carry costs.

These costs to deliver gene therapies to patients are coupled with high manufacturing costs to drugmakers. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to produce viral vectors that are used to deliver the genetic material to the cell. Global consulting firm Roland Berger estimatesExternal link that the cost of manufacturing one dose could be in the range of $1-2 million.

Weighing risks and benefits

There are also still a lot of uncertainty surrounding the benefits and risks of the therapies themselves.

Some gene therapies, such as Zolgensma sold by Swiss firm Novartis for the rare neuromuscular disease spinal muscular atrophy, have transformed the lives of patients. In February, the US company MeiraGTx reported that its gene therapyExternal link had enabled 11 children who were born blind to see.

However, not all patients have benefited to the same extent. Children who received Zolgensma before they showed symptoms of spinal muscular atrophy had much better outcomes than those who received it later. Some people also experienced serious side effects including acute liver failure.

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

While safety has been improving, there is still more work to do, said Renac. “Other new treatments can also carry risks, but the stakes are higher for gene therapies because of the price tag.” Investors massively invested in gene therapies on the promise of curing diseases but this also has to be balanced with the risks.

Other types of gene therapies that use CRISPR-Cas9 cut DNA in a specific location and correct or insert new genes. Experts believe this could allow for more permanent benefits to patients, but they can also lead to unintended genetic changes. Thus far, only one CRISPR-based therapy, Casgevy for sickle cell disease, has been approved by US and European medicines authorities.

It also isn’t clear how long the benefits last. The latest dataExternal link on Zolgensma show that many children maintain outcomes a decade after receiving treatment. However, some scientists suggest that gene therapies’ benefits could wear off as cells die and divide, potentially requiring patients to receive another dose.

In the face of the uncertainty, not every patient or doctor has embraced the technology. For some diseases such as haemophilia, there are already established treatments that may be easier to administer, cheaper in the short-term, and have solid evidence of long-term benefits.

“There is some reluctance towards new, one-time treatments,” said Monika Paule, CEO of Crispr-specialised biotech Caszyme, at the Sachs CEO Life Sciences Forum in Zurich in February. “Especially when there is an opportunity to use a treatment that is continuous and still allows the patient to live a normal life. Patients often choose this because they are familiar with it.”

Patients also have to weigh the fact that they are typically excluded from taking other treatments if they use a gene therapy – even if it fails to work for them.

“It’s been harder to find and convince patients about gene therapies than people thought,” Renac said. “Some big pharma companies launched them like any other medicine, but gene therapies require a different approach to engaging with patients and healthcare providers.”

Solutions in sight

Given the challenges, some companies have abandoned the field. In February, US firm Pfizer announced it was discontinuing its haemophilia B gene therapy Beqvez, which had already been approved by US authorities, leaving no active gene therapy programme in the company’s portfolio.

Swiss company Roche also removed at least three gene therapies from its pipeline over the last couple of years. In early April, Roche and European regulators halted some studiesExternal link of a gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy after a 16-year-old boy treated with it died of acute liver failure.

In 2023, Roche’s CEO of Pharmaceuticals Teresa Graham told journalists on an earnings callExternal link in 2023 that “developing in the gene therapy space is exceptionally difficult,” and that there is still difficulty “creating a treatment that is actually going to be maximally impactful and durable over time”.

The company is still investing in gene therapies but more selectively. Last October the Basel-based company signed a deal with Dyno Therapeutics to use AI to improve the way gene therapies are delivered to their target. Roche will pay $50 million upfront to Dyno and more than $1 billion in milestone and royalty payments if the treatments are a success.

More

Roche’s big bet on big diseases

Swiss company Novartis also announced last year it was acquiring Kate Therapeutics, a biotechnology start-up founded four years ago, which has two gene therapies in early stages for rare, genetic muscle disorders. The deal could be worth up to $1.1 billion.

As academics and drugmakers work on safer, more effective gene therapies, some solutions to the market challenges are emerging. Most countries and insurers are using risk-sharing mechanisms in the way they pay for gene therapies according to a reportExternal link by contracting firm Lyfegen published in March. In some cases, insurers only pay for a treatment when certain patient outcomes are achieved.

Parle from Lyfegen said that data tracking and analytics tools, as well as AI will also help generate a complete picture of the impact of a given drug on the overall healthcare system. There’s also more attention on the communication and engagement with patients and doctors, including understanding fears and concernsExternal link.

“Gene therapies can achieve remarkable outcomes for patients, but they are still risky at this stage,” Renac said. “They are very disruptive, very novel and still risky.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.