Romansh seeks to revive its fortunes

Romansh, Switzerland’s fourth national language, has fewer speakers than Serbo-Croat, but absorbs more resources than the country’s three official languages.

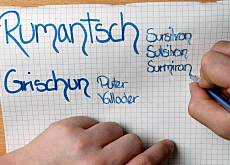

It survives in the form of several dialects, five written variants and a standardised composite: the controversial Rumantsch Grischun, which is only starting to make inroads.

On a purely numerical basis, Romansh is not the fourth but only the tenth most widely spoken language in Switzerland, after Serbo-Croat, Albanian, Portuguese, Spanish, English and Turkish, as well as the country’s three official languages – German, French and Italian.

In Switzerland, just over one in 200 people claim Romansh as the language of which they have the best command.

But data from the 2000 census shows that in fact that almost twice as many people – more than 60,000 – claim Romansh as their daily language.

Numbers and culture

But the Romansh-speaking community is dwindling, and losing its political clout at the same time. Judging by numbers alone the country’s financial commitment to its Romansh minority might seem excessive.

The federal government and canton Graubünden contribute roughly SFr5 million francs ($3.93 million) per year, while another SFr21 million are taken from licence fees to pay for Romansh Radio and Television. This funding amounts to far more per head than for other language communities.

Chaspar Pult, former president of Lia Rumantscha, the association that promotes Romansh language and culture, says that considering numbers alone is the wrong way to analyse the situation. “Respect for minorities cannot be interpreted on a purely proportional basis,” he added.

Minority languages are subject to strong pressures in Switzerland, especially when the bottom line predominates. The country’s biggest language group, German speakers, often complains about the amounts spent on linguistic minorities.

“In the ‘new economy’, efficiency has become the ruling criterion,” Pult told swissinfo. “But a minority language can be defended only on cultural, historical and psychological grounds. Nowadays, these are hardly priorities, so Romansh is under threat.”

Fragmented

Romansh, like its Italian “cousins” Ladino and Friulano, developed in the Alpine region, when Latin was grafted on to the long-forgotten Rhaetian language.

The linguistic history of the region has resulted in a mosaic of different dialects that, in canton Graubünden, have crystallised into five written variants – sursilvan, sutsilvan, surmiran, puter and vallader.

The limitations of this fragmentation were already evident in the early part of the 19th century, when Graubünden became part of the Swiss Confederation. With German, the dominant language, making immediate inroads, Romansh dialects were under pressure from the start.

Despite earlier attempts, it was not until 1982 that Rumantsch Grischun emerged, a compromise written language devised to supersede the five historic variants.

But if the cantonal and federal authorities favour it, the composite language has encountered resistance from Romansh speakers who do not want to give up their own dialects. They also do not see the need for a language to use in situations, such as law courts, where they can get by very well in German.

Chaspar Pult is convinced that the language project is worthwhile though.

“We need to have texts in Rumantsch Grischun to give the language visibility and generate vocabulary,” he said. “If we make the effort to create new words, it is possible they will come into everyday use.”

Val Müstair

The standardisation represented by Rumantsch Grischun has led to more widespread use of Romansh by the cantonal administration, and also to the idea of creating a user interface and spell-checker for Microsoft Office.

However, if the aim is to achieve some sort of linguistic unification of Romansh speakers, education is part of the equation.

The cantonal government approved last year a plan to introduce Rumantsch Grischun into schools as the formal written language. This was partly for financial reasons: printing textbooks in five different dialects is expensive.

But local authorities have been less than enthusiastic about the plan.

It came as a surprise then when 65 per cent of the people of Val Müstair voted in favour of Rumantsch Grischun being used in their schools. For Pult, this is a step in the right direction, because “the future depends on having a unified written language”.

swissinfo, Doris Lucini

In 2000, 60,651 people (0.8 per cent of the population) speak Romansh as their main language in Switzerland.

The 1990 figure was 66,082, or one per cent.

35,095 (0.5 per cent) claim Romansh as the language of which they have the best command.

Since 1983, a super-regional written language, Rumantsch Grischun, has existed alongside the five older written variants of Romansh.

Rumantsch Grischun is the result of comparing and harmonising five written variants of the Romansh language.

Since 1996, it has been used as an official language of canton Graubünden and of the Swiss Confederation.

Work done to make Rumantsch Grischun viable includes the creation of a language database, vocabulary, and grammar.

The Graubünden government intends to introduce it gradually into primary and secondary schools.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.