The legacy of Chernobyl

Twenty years after the world's worst nuclear accident, swissinfo travelled to Chernobyl to find out how Switzerland is helping Ukraine to move on.

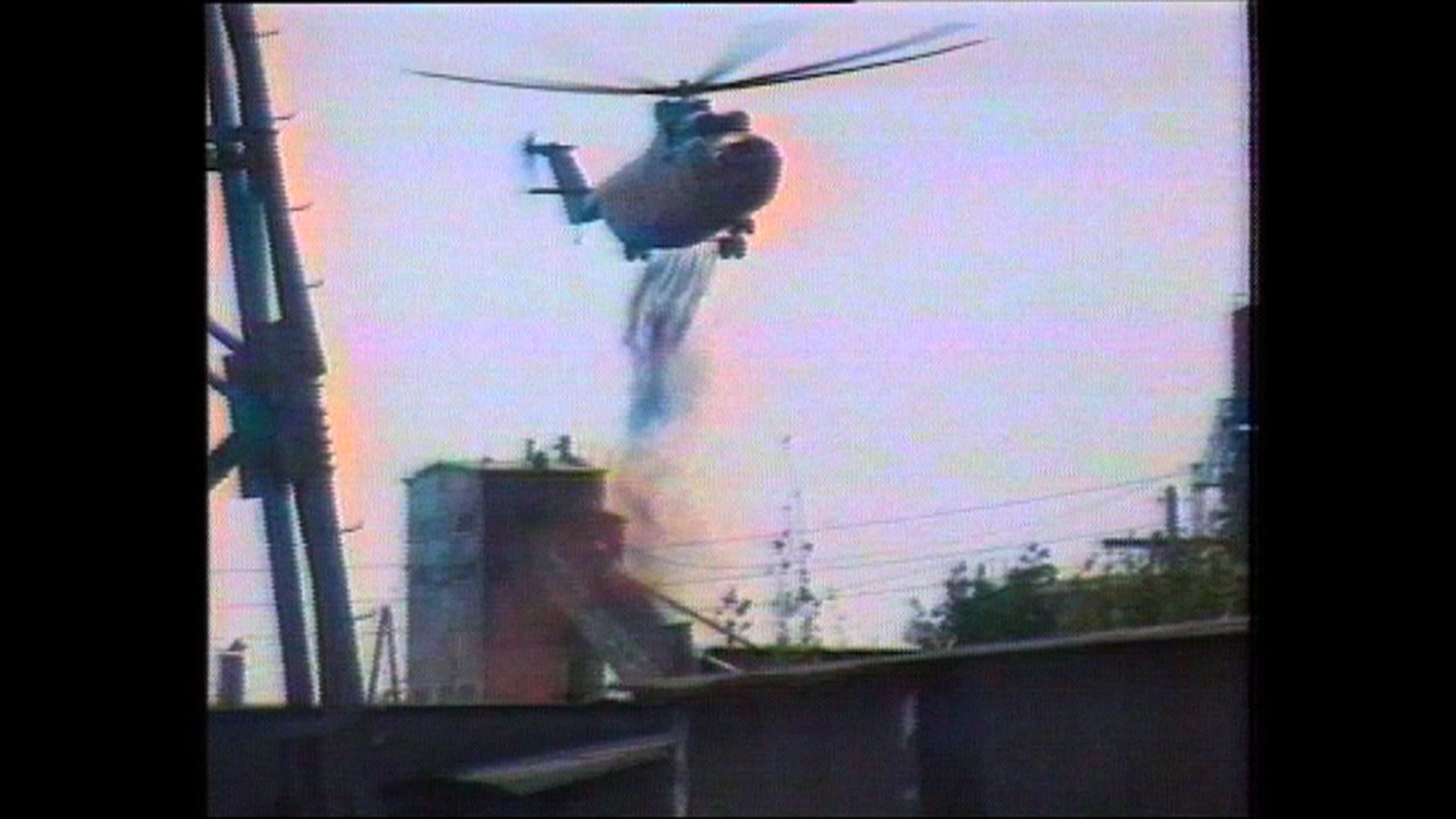

In April 1986, a combination of careless work practices and the poor design of the Chernobyl power plant’s safety systems led to an explosion in reactor number four.

The heat from the meltdown ignited a vast pile of carbon and the resulting fire spread a plume of ionizing radiation across much of Europe. It was several days before the Soviet authorities admitted that there had been an accident.

In the central Swiss city of Lucerne, radiation levels rose from the normal ten to 30 micro Roentgen per hour, and parents were advised to keep their children indoors.

In the southern lake of Lugano, scientists noted increasing radiation levels among various fish varieties, and a fishing ban was imposed.

It was much worse for millions of people in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine who were exposed to very high levels of radioactivity. Local children suffered a ten-fold increase in thyroid cancer, and there is deep concern about possible long-term genetic damage to future generations.

Visiting reactor four

The countryside around Chernobyl has become a wilderness. The 30km evacuation zone surrounding the reactor, with its 200km fence, is a silent witness to the persistent effects of the explosion 20 years ago.

At that time, there were 90 villages here – home to more than 130,000 people. Most of these were forcibly evacuated but a few have returned illegally, sneaking through unmanned parts of the barrier fence, to resume their lives in what will remain a highly contaminated area for hundreds of years to come.

Visitors need a special pass to enter through a series of checkpoints manned by armed guards. Our guide, Yuri Tatarchuk, is an information officer from the Ukrainian Ministry of Emergencies. He carries a monitor to measure radiation levels.

We stop near a sluggish river about a kilometre from the giant concrete reactors and ventilation chimneys that now lie dormant. The gamma ray counter shows 150 micro Roentgen, ten times the pre-accident level of background radiation for this area.

There’s worse to come. As the minibus races through a forest, where the bare branches of dead trees scratch the skyline, the monitor hovers near 1,800 micro Roentgen. This is clearly no time or place for a picnic.

Arriving at the ruined reactor with its enormous, hastily constructed concrete cover, we see cranes moving to and fro as welders race against time to shore up the metal supports of the structure, which threaten to collapse at any moment. Radiation from 200 tons of nuclear waste stored here has begun to seep through fissures in the sarcophagus.

Shelter fund

As it is too dangerous to enter Reactor 4, we are taken to a nearby reception centre with a model of the stricken plant, and designs for the new shelter that will cover the crumbling sarcophagus, and protect the public for a further 100 years. It will be funded by the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and should be finished by the end of 2008.

As an EBRD donor, Switzerland has played a key role in helping to make Chernobyl safe.

Over the past ten years, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco) has contributed SFr20 million ($15.5 million) towards decommissioning the power plant. Since 1997, SFr15 ($11.6 million) has been paid into the shelter fund.

The Geiger counter in the reception centre jumps to 1,250 micro Roentgen. A Ukrainian government spokesman explains that, even if we were to spend seven hours here, we would still only absorb one tenth of the amount of gamma rays emitted by a conventional x-ray.

But for the 4,000 workers employed here, the average monthly wage of SFr310 ($240) scarcely seems to compensate for the risk they are taking.

Pripyat

In 1970, when the power plant was constructed, a modern Soviet city called Pripyat sprang up 3km away to house and entertain 47,000 workers.

“The day after the accident, there were radio broadcasts telling people to evacuate the city within three days, taking with them only the bare necessities,” Tatarchuk told swissinfo.

“They fled by the busload. People were not allowed to come back, as radiation levels are very high in some places and it is not safe to live here.”

Relocation was a deeply traumatic experience, which often left people unemployed and feeling they had no place in society. Switzerland is among the countries that continue to provide humanitarian aid to the villages where many of the evacuees settled.

Inside Pripyat’s apartment buildings, children’s dolls, shoes and newspapers from the time of the accident litter the floors. Clearly, people panicked in their hurry to leave.

Tall weeds grow between the paving stones outside the hotel and restaurant in the city centre. The once proud emblem of the Soviet state crowning the palace of culture grows rustier as the seasons pass.

Many of the scientists who were evacuated from here to Kiev, the Ukrainian capital, are now dead from radiation-linked diseases.

This ghost town is their mausoleum, and the defunct power plant will remain the most vivid symbol of the legacy left after the Soviet Union collapsed.

swissinfo, Julie Hunt in Chernobyl

800,000 people were drafted in to help clean up after Chernobyl.

The WHO expects 8,000 clean-up workers and local residents will die.

The major health hazards come from iodine 131 and caesium 137.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.