Following in Lord Byron’s Swiss footsteps

Two hundred years ago, the great British poet Lord Byron retreated to Switzerland with fellow Romantics for what would become an exceptionally creative summer. It would also have a lasting impact on tourism to the area.

In 1816, 28-year-old George Gordon Byron left England by boat for self-imposed exile. The disgraced literary star travelled through Belgium and Germany to Switzerland, where he stayed from May 20 to October 10, meeting up with an entourage that included poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Godwin (future Mrs Shelley) and her stepsister Claire.

They rented summer houses at Cologny, near Geneva, and spent part of their time boating and visiting Geneva, Lausanne and the Château de Chillon. Fleeing nosy locals and British tourists, and often stuck indoors due to bad weather – blamed on an Indonesian volcanoExternal link – the creative juices flowed.

“Everybody was spying on Byron and spreading rumours. The idea he was drinking a lot and taking drugs was a myth. He mainly just wrote when he was here,” explained Patrick VincentExternal link, professor of English and American literature at the University of Neuchâtel. He was a consultant on the “Byron is back” exhibitionExternal link that recently opened at the castle. It commemorates the anniversary and showcases original documents and objects.

“He was depressed about leaving England and the fact that his wife had left him. He felt guilty and abandoned by his half-sister. There was this tension which was so inspiring and led to great creativity over those five months.”

Their summer culminated in Byron’s poem The Prisoner of Chillon, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and a short story by young physician John Polidori called The Vampyre, which was influence for Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Travel bug

Those five months have undoubtedly had a huge impact on English literature, and culture in general. But Byron’s visit to Switzerland has had other enduring influences, most notably on tourism.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, visiting Europe on the so-called Grand Tour was an educational rite of passage for many young aristocrats, artists and philosophers. By the time of Byron’s visit after the Napoleonic Wars, growing numbers of middle class Europeans had also got the travel bug.

In the Romantics’ letters from the times, we learn that several thousand English tourists were staying in Geneva in 1816 and had booked up many of the country homes.

“The Romantics like to think they were alone, when in fact there were lots of people all around them and looking at what they were doing as they were so notorious,” Vincent explained.

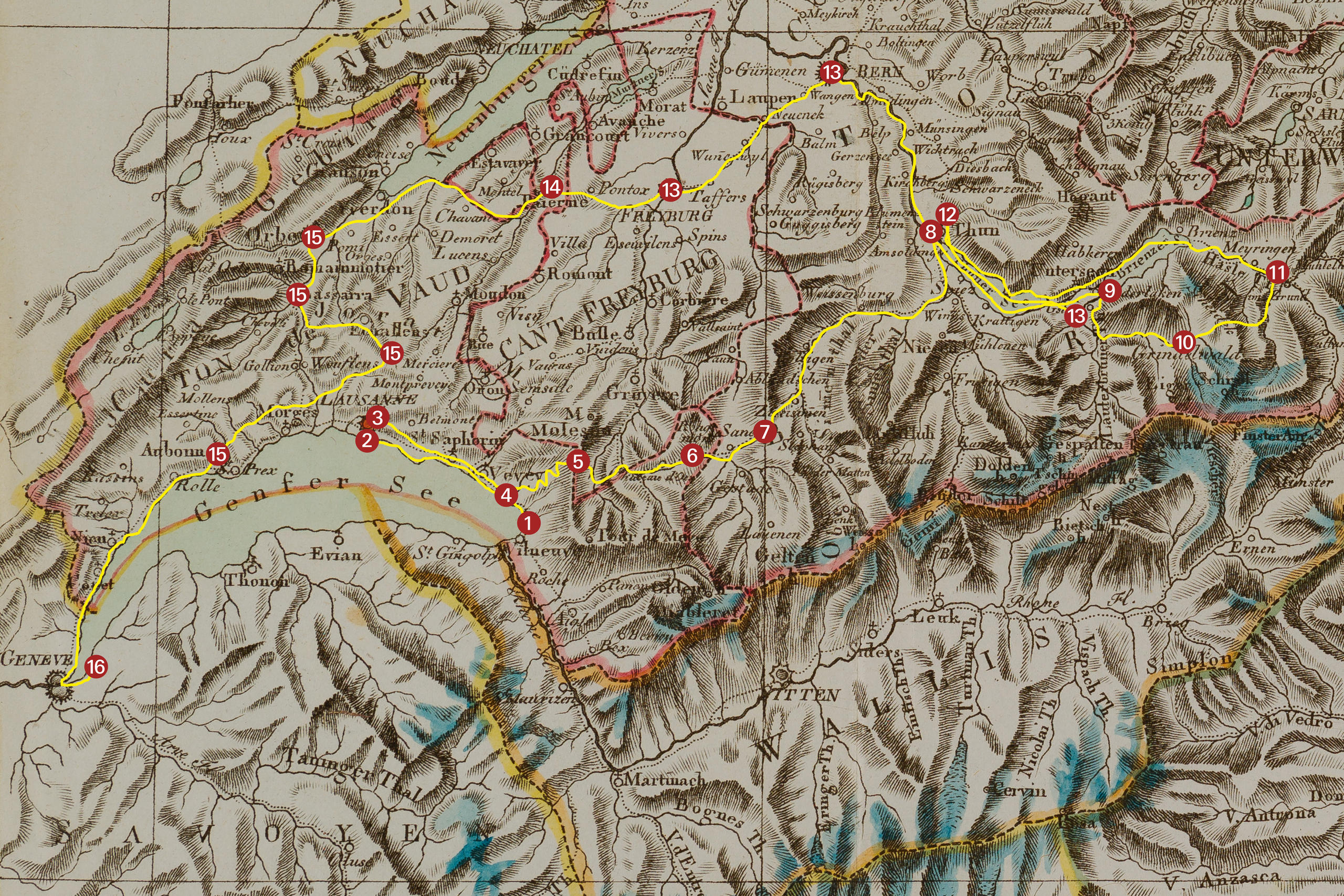

1. June 25, Clarens and Chillon Castle; 2. June 27-28, Lausanne-Ouchy; 3. September 17, Lausanne-Ouchy 4. September 18, Vevey, Clarens, Châtelard Castle, Chillon Castle; 5. September 19, Col de Jaman, Dent de Jaman ; 6. September 19, Montbovon 7. September 20, Rougemont, Vanel Castle, Zweisimmen ; 8. September 21, Weissenburg, Wimmis Castle, Thun, Schadau Castle ; 9. September 22 Lake Thun to Neuhaus by boat, Unspunnen Castle ruins, Trümmelbach Falls and Staubbach Falls ; 10. September 23, Kleine Scheidegg, Lauberhorn, Grindelwald glacier; 11. September 24, Grosse Scheidegg, Rosenlaui Valley, Reichenbach waterfall and Hasli baths; 12. September 25, Thun; 13. September 26, Lake Brienz to Interlaken by boat, Bern, Fribourg cathedral; 14. September 27, Payerne; 15. September 28, Orbe, La Sarraz, Aubonne; 16. September 29, Cologny, Villa Diodati.

After Lake Geneva, Byron toured the Alps on horseback and by carriage with his companion John Cam Hobhouse, following a guidebook route. They both kept diaries. In Byron’s Alpine Journal, written for his half-sister Augusta, the nature-lover waxes lyrically about the landscape, the quality of his mattress and singing locals.

“In the evening, four Swiss peasant girls from Oberhasli came and sang the airs of their country… the airs are so wild and original and at the same time of great sweetness,” he wrote.

“God pelting the Devil with snowballs”

From Montreux they climbed the nearby Col de Jaman mountain and travelled to canton Bern.

“French exchanged for bad German – the district famous for cheese – liberty – property – and no taxes,” wrote Byron.

They went on to Lake Thun, the Lauterbrunnen Valley and the Staubbach Falls, which resembled “the tail of a white horse streaming in the wind”.

As they ascend the Lauberhorn, Byron gazes in wonder at the Jungfrau and Eiger mountains.

“Heard avalanches falling every five minutes nearly – as if God was pelting the Devil down from Heaven with snow balls… clouds rose from the opposite valley curling up perpendicular precipices – like the foam of the Ocean of Hell during a Springtide.”

His alpine trip would inspire his poem Manfred, which was later set to music by Tchaikovsky External linkand SchumannExternal link.

Hobhouse’s alpine diary is more down to earth. He is amazed by the sights but complains about getting ripped off by innkeepers, crowds of English, and peasants who are “too accustomed to tourists”.

As Byron swoons over the Jungfrau, Hobhouse describes how the sudden arrival of “two or three females on horseback” shatters the illusion of ‘wildness” up on the mountainside.

While struck by the beauty of the countryside, Byron’s attitude towards the Swiss people is ambivalent, however.

“Switzerland is a curst selfish, swinish country of brutes, placed in the most romantic region of the world. I never could bear the inhabitants, and still less their English visitors,” he wrote to Thomas Moore in 1821.

More

Byron’s Swiss tour

At the time, alpine trips were all the rage. According to British historian Gavin de Beer, around five books on Switzerland were published every year in Europe in the second half of the 18th century. From 1845 to 1850, 40 travel-related works on Switzerland sometimes appeared a year.

In 1816, the year the Prisoner of Chillon was published, Byron-mania was also at its peak. His flight abroad had not dampened interest – quite the contrary.

From then up until around 1850, Byron fans, including French writer Victor Hugo, made pilgrimages to Lake Geneva, the Château de Chillon and the Alps to follow in his footsteps.

They were assisted by books like Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland, published in 1836 by the son of Byron’s English publisher. Packed with Byron quotations, tourists could relive his emotions in front of the Jungfrau and at other spots.

“Byron stayed here”

Local entrepreneurs were also quick to exploit the literary rock star’s appeal. “Byron stayed here” plaques appeared on buildings and English tourists packed new establishments like the luxury Hotel Byron near the Château de Chillon, inaugurated in 1839.

“Tourism was already quite big, but Montreux, Vevey, Clarens, Villeneuve and Caux developed a great deal because of Byron,” said Claire Halmos, curator of the Byron exhibition.

Today, the Hotel Byron is an old people’s home. Other deceased artists, like writer Vladimir Nabokov or singer Freddie Mercury, have joined the list of famous former residents or visitors who the regional tourist office likes to cite.

But Byron’s influence has not waned. For years, the Château de Chillon has remained the most-visited historic monument in Switzerland. In 2015, almost 372,000 people crossed its drawbridge and admired the Byron graffiti in the dungeon. British visitors (2.5% of total) have, meanwhile, slowly been replaced by Swiss (24%) and Chinese (20%).

Literary summer

To commemorate the summer of 1816, Château de Chillon, near Montreux, and the Martin Bodmer Foundation in Geneva are hosting complementary events from both sides of the lake.

The ‘Byron is back’ exhibitionExternal link at the Château de Chillon from April 28-August 21 marks the poet’s Swiss summer and the impact on regional tourism.

The ‘Frankenstein, Creation of Darkness’ exhibitionExternal link takes place at the Martin Bodmer Foundation from May 14 to October 9.

The historic images came from the Château de Chillon, the Martin Bodmer Foundation and the VIATICALPES-VIATIMAGESExternal link database.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.