The strengths of a ‘weak’ Swiss government

For 175 years Switzerland’s seven-member Federal Council has led the country through thick and thin, earning a lot of trust. The secret of its popularity also lies in the accessibility of its ministers.

At first glance, it looks like one of the many restaurants that can be found across the Swiss capital, Bern. Good food and wine, outdoor seating and friendly hosts. But there are four things that make this restaurant stand out: its location, its name, its dining room and its clientele. Located next to the Swiss National Bank and opposite the Federal Palace overlooking Parliament Square, the Café FédéralExternal link sits right at the political heart of Switzerland.

Portraits of all the women and men who have governed Switzerland over the past 175 years cover the walls of the first-floor dining room. Back in the day, cabinet ministers met here for lunch after their weekly parliamentary sessions.

Today, ministers usually don’t have time for such intimate lunches with their peers, but they are still up for a quick coffee and a chat with old and new acquaintances. When they meet in the Café Fédéral or anywhere else in Bern, they usually turn up without police protection or bodyguards. Mingling with the public and experiencing their everyday life is an integral part of a political system that is not only efficient by international standards but is also valued as a democracy.

Statistics published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) clearly show that the Swiss are very satisfied with their country’s political efficiency and their democracy, while the population of neighbouring Italy feels the complete opposite about their government.

More

In autumn 2022 the post-fascist politician Giorgia Meloni took the helm of the 68th government in 77 years. Since 1946, as many as 1,300 ministers have been sworn into office in Italy, while in Switzerland only 121 ministers have vowed to uphold the Constitution since it was adopted in 1848. In other words, Switzerland “goes through” 25 times fewer government officials a year than Italy.

A study by the University of BernExternal link shows that one significant reason for this is the extremely high level of trust the Swiss have in the seven-person Federal Council, which forms the government. According to the Federal Statistical Office, public trust in the government has been on the rise for the past 20 years.

But it’s not only the facts and figures that distinguish the Swiss government from the executive branches of other countries. Political scientist Rahel Freiburghaus has found other practical differences that set the Swiss apart, for example the government’s role in politics.

“Compared with other countries, the Swiss government is not the sole decision-maker; it’s more of a mediator who brings together the different interests of the population,” she said.

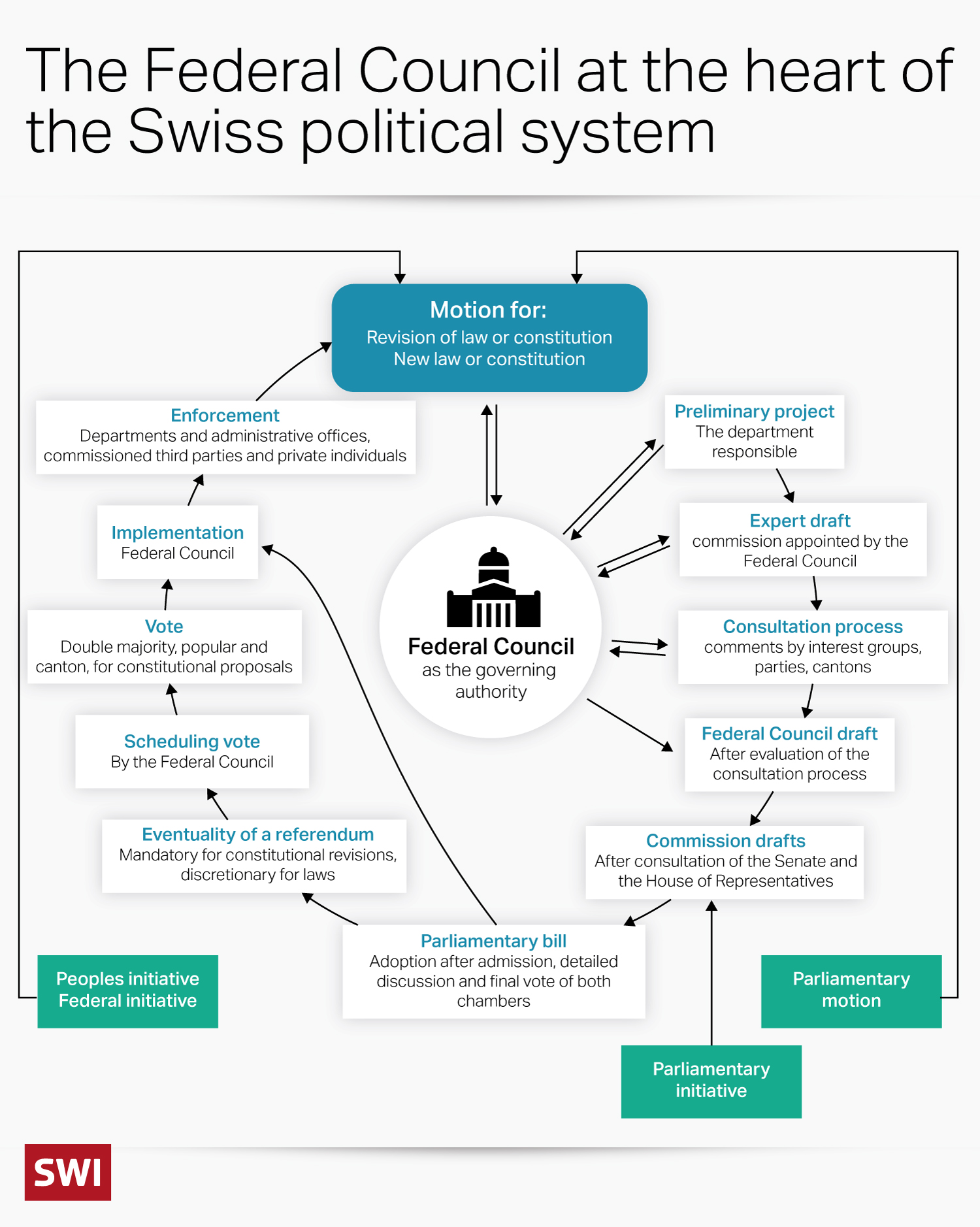

One of the reasons is that through their popular rights the Swiss have the opportunity to put every new law to a referendum or bring about constitutional amendments by launching a popular initiative. “While the government has to fully and transparently inform the Swiss citizens about an upcoming federal vote, it sometimes has to act as a mediator between the cantons,” she explained.

Since 1848, when the founding fathers – women and other parts of the population were excluded from voting for a long time – created the Federal Council as the executive body, the system has largely remained unchanged: in the past 175 years, several attempts to launch reforms, such as enlarging the Federal Council or introducing direct federal elections, have failed. Three such initiatives were put to the people in 1899, 1939 and 2011 and were rejected.

As the parties nominate the ministers and the members of parliament elect them, the parties have to reject certain politicians when it comes to selecting candidates for high-level government positions who are likely to win a majority. “We do not need sharp-tongued doers who follow the party line; we need team players with good communication skills,” Freiburghaus said.

This is the only way to find viable solutions in Switzerland’s multi-layered political system of divided powers. After all, the Federal Council is at the centre of the political decision-making process.

For a long time, observers and experts struggled to find the right category that defines the Swiss system, as it fits neither in the parliamentary nor the presidential box. In parliamentary democracies like Italy, the United Kingdom and Australia, voters directly elect the parliament which, in its majority, has the power to determine the government, but can also overthrow it.

In a presidential system like in the US, the House of Representatives and the Senate are elected by direct popular vote. So, how does it work in Switzerland? Here, the majority of parliament – which consists of the House of Representatives and the Senate – votes for every government member individually and according to their seniority. The system does not allow for a minister to be removed in the four years between elections, and it hardly ever happens that one of the seven ministers does not get re-elected. Since 1848, this has occurred only four times, most recently in 2007 when former Justice Minister Christoph Blocher lost his seat in government.

No head of state

The fact that the Swiss government does not have a head of state also distinguishes it from other countries. The role of the president rotates annually among the ministers and adds to their duties at home and abroad, but it does nothing to increase their power.

Like other democratic ideas inspired by the French Revolution, such as direct democratic rights, the concept of collegial government was quickly abandoned in centralised France but found fertile ground in Switzerland, which consisted of many small political communities. The collegial system was given constitutional status in 1848.

Scarce resources for parliament

Another democratic idea of the French Revolution was to support a strong legislative branch (parliament) and a weaker executive branch (government).

“In legal terms, the Federal Council forms one of the weakest governments in Europe,” says Adrian Vatter, professor of Swiss political science at the University of Bern and author of the book “Der Bundesrat – die Schweizer Regierung” (The Federal Council – the Swiss government).

This, however, is only half the story. “The Swiss parliament has a lot of power, but resources are scarce, and it is not very professionalised.” For this reason, the powers between the legislative and executive branch are fairly well distributed in Switzerland.

Even though the “directorial system” with its mini cabinet has worked well in everyday life, the Federal Council regularly comes under fire in times of crisis.

This was the case in 2020, at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, when the government postponed a scheduled referendum, or in spring 2023, when Switzerland’s biggest bank UBS took over its crisis-ridden rival Credit Suisse. In both cases the government applied emergency powers as a last resort which triggered new debates on the strengths and weaknesses of the Federal Council within the Swiss political system.

This, however, is a question that increasingly affects individual members of government in times of media influence and personalisation. Switzerland’s tabloids regularly conduct popularity polls, which have recently found that Defence Minister Viola Amherd is the minister most Swiss would like to meet for a coffee at the Café Fédéral.

swissinfo.ch, Bruno Kaufmann

Edited by Mark Livingston. Translated from German by Billi Bierling

Governing in times of crisis

In Switzerland, federal laws are generally subject to an optional referendum. This means that a new law can be challenged by popular vote if 50,000 signatures are collected within 100 days of the official publication. In case of urgency, the majority of the legislative power can allow the law to come into force immediately. A possible referendum will only take place afterwards.

The Federal Council’s emergency powers as they stand today were introduced in 1999 when the Federal Constitution was revised. The Federal Council can apply emergency powers based on articles 184 and 185 of the Swiss Constitution. Emergency powers were first applied in 2008 when Switzerland’s biggest bank UBS was rescued. In 2020 it was applied 18 times during the Covid-19 pandemic and was last used in 2023 when the government bailed out the collapsed bank Credit Suisse.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.