Test screenings: where the audience makes the final cut

“Testing” a film before its release, a common practice in many countries, is now being adopted by Swiss filmmakers. But how helpful can the audience be? Directors share their experiences.

If you’re a fan of the Scream franchise, chances are you have a soft spot for Dewey Riley, the law enforcement officer played by David Arquette. A key member of the original cast across five films, Riley was originally meant to die at the end of the first film. However, while shooting the film, the director, Wes Craven, had a hunch that audiences would like the character and shot an additional scene in which he’s shown to be alive. The scene was to be used in case feedback from the test screening argued that his character should remain. That’s exactly what happened.

Test screenings, a standard practice in the film industry, mainly in Hollywood, can lead to all kinds of changes in a film’s DNA. Sometimes these can be as simple as a change of title or the timing of a joke.

Screen-testing has progressively been exported outside the United States. This year, for the first time, the Solothurn Film Festival held a test-screening session. The aim was to gauge audience reactions for an upcoming title which was part of this year’s Focus, a section of the festival devoted to wider, not necessarily Swiss-centric subjects. Neither the title of the film nor the date of release was revealed.

SWI swissinfo.ch was not granted access to the test screening, for the festival specified that the audience had to consist entirely of people with no ties to the film industry. But this inspired us to reach out to Swiss filmmakers for their take on the practice, which is gaining ground in Switzerland.

Timing is everything

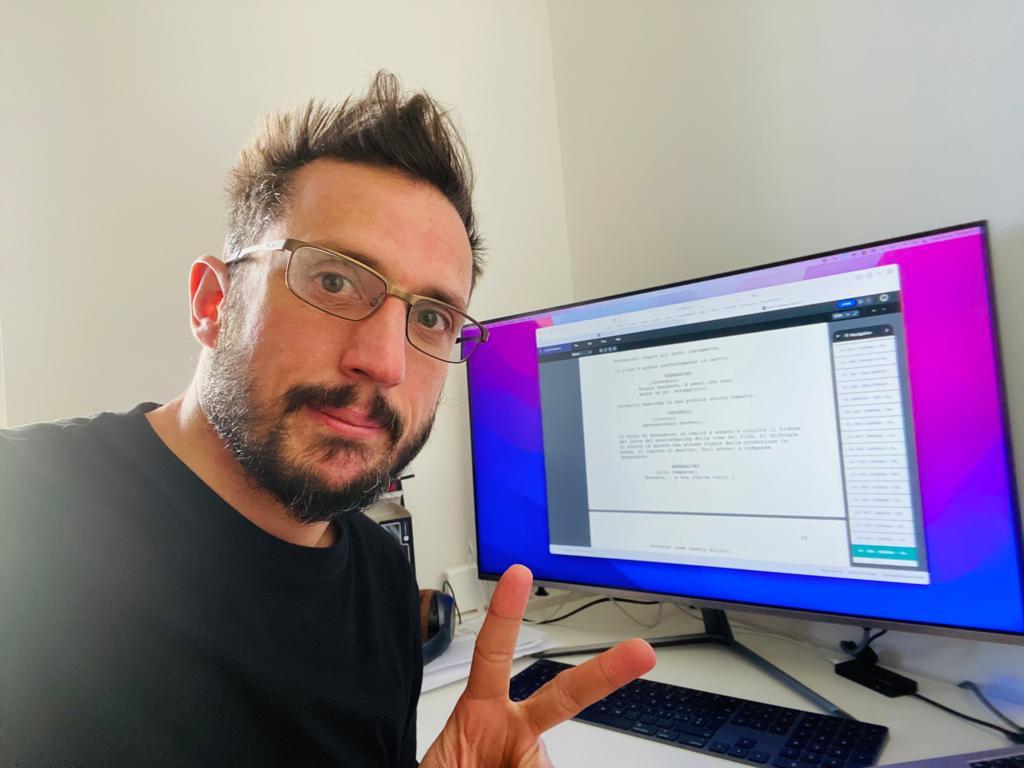

We learnt that, unsurprisingly, test screenings can prove crucial for comedies, since timing is everything for a joke. Alberto Meroni, who’s currently writing the script for the sequel to the 2017 hit Frontaliers Disaster, explains why he greatly values audience feedback.

“I’ve always done test screenings for my films, and in the case of Disaster we did one a month before it was due to open, to check the timing of the gags as well as the sound levels,” he says. Even then, Meroni released several versions of the film to the public before he was finally satisfied with the result.

“We kept tinkering with it for three weeks. Every few days I would send exhibitors a new DCP [digital cinema package], because I was sneaking into screenings and assessing viewers’ responses. The fifth cut was the final one.” Well, almost: the film went through an additional dubbing session for the theatrical release in Italy, as some jokes at the expense of Swiss celebrities wouldn’t make sense abroad.

Louder laughs in a full room

It was also a laughing matter for Natascha Beller, who entertained Locarno’s Piazza Grande audience in 2019 with her feature debut Die fruchtbaren Jahre sind vorbei (Vagenda Stories), about a woman’s quest to get pregnant before she turns 35. During post-production, she screened a rough cut – “the editing was maybe 80-90% finalised” – and the test audience consisted entirely of people she had never met. “We hoped their feedback would be neutral,” she says.

Looking back at the experience, she wishes she had done more than just one screening, as the sample was too small to get a proper assessment of the film’s comic strengths. “People tend to laugh louder when the room is full,” she notes, having witnessed this for tapings of the Swiss late-night television show Deville.

Several screenings

One major change Beller made prior to the screening was the title: the original one was Ü30 (“over 30”), which drew mixed reactions from the test audience, as well as a remark from the distributor that it might alienate viewers under 30 and over 40.

Beller plans to repeat the experience for future projects. “If the budget allows, I’d do more than one screening, with a larger audience, in different cities.”

In the case of Azor, Andreas Fontana’s acclaimed financial thriller set in Argentina, there were multiple screenings throughout post-production. The screenings began with a core group of “testers”, including Fontana himself, the editor, the two main Swiss producers, and the film’s artistic consultant. They then gradually brought in other people, with a keen focus on viewers with no ties to the film industry. “We had to assess how understandable the film was, as it’s very dense,” he explains.

One early screening proved vital for the film’s main character. “We showed a preliminary cut at the CityClub Pully [a cinema in a suburb of Lausanne]. It was a friends-and-family screening, barely half a dozen people,” he recalls.

“At the end of that screening we realised we had done the main character a disservice: he appeared too weak, too oppressed by what was happening, which made him annoying and not that mysterious. So we went back to all his appearances in the film – which is a lot because he’s in every single sequence – and we adjusted by removing one third of the shots featuring him and using alternative takes.”

Vox populi

Fontana also mentions a key difference between showing the film to regular viewers as opposed to fellow filmmakers.

“The latter tend to offer solutions, based on their own taste and desires. On the other hand, people outside the film industry gave general feedback, identifying symptoms rather than causes, and then it was up to us to figure out how to fix it,” he says.

Finally, Elie Grappe, director of international success Olga, tells us he was sceptical of the process, especially the cards audiences are asked to fill out – “I thought it was a bit of a clinical approach”. But in the end he valued the reactions from one specific screening of Olga, his debut feature film, which was shown in an almost complete version to a class of high-school students.

“We still had two weeks of post-production to go, and we often referred back to the questionnaires. They validated some elements we wished to defend and revealed some remaining weak spots with fresh eyes,” he says.

“It’s also fun to see how test audiences can pinpoint something as an error, that you should amend or remove altogether, and it’s actually an important element of the film, even though you haven’t figured it out yet. That was the case with our use of archive footage, and we found the right balance as we went on with the editing.”

More

Olga, Elie and Oscar: the story of a remarkable Swiss film debut

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!