Veiled in history: how women have been covered up

On Sunday March 7, when Switzerland voted to ban the burka, many were quick to see it as a matter more of symbolic value than of political effect. But symbols of women do matter in the political arena, and the veiling of female faces and bodies has long been a contentious issue – long before the birth of Islam.

In recent years it has mainly been Christian countries, especially in Europe, which have had issues with women wearing the veil, seen today as a form of radicalised Islam. Historically though, it was Christian and Jewish women who were the primary wearers of the clothing before the birth of Islam.

In Christian tradition, the veil was a symbol of dignity, chastity, and virginity. More generally, the question of the female dress code – and its relation to piety and the observance of moral codes – is part of Christianity and has been imposed throughout the centuries by heads of Churches.

In the Middle East, several countries have attempted to regulate the clothing. In Turkey, the veil was banned in public institutions from the 1930s. For many years, in urban areas across the region, the veil was a rare sight. During the 1970s, however, mass migration from rural areas to towns and cities brought with it women who wore the veil, albeit more for reasons of tradition than of religion.

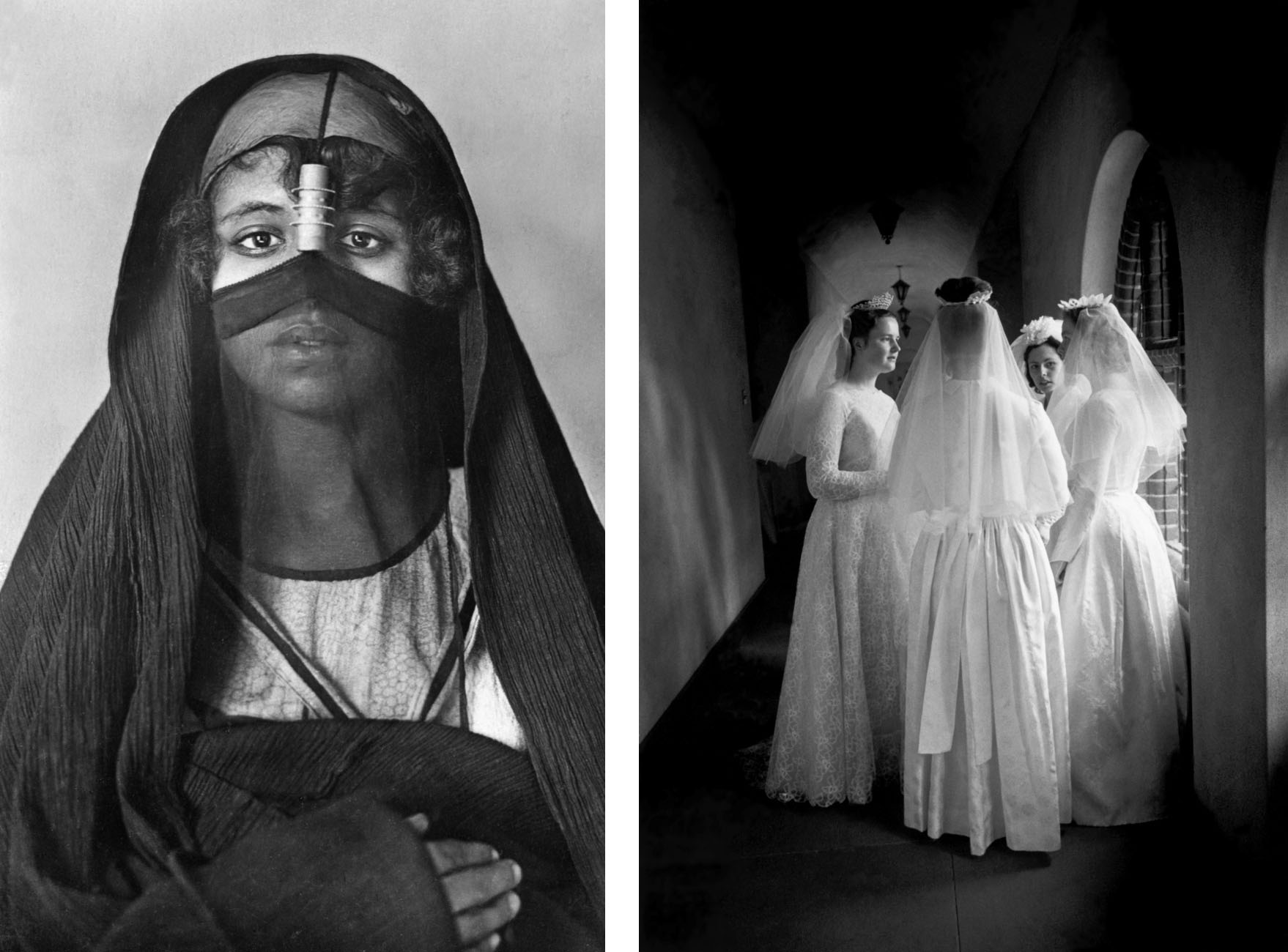

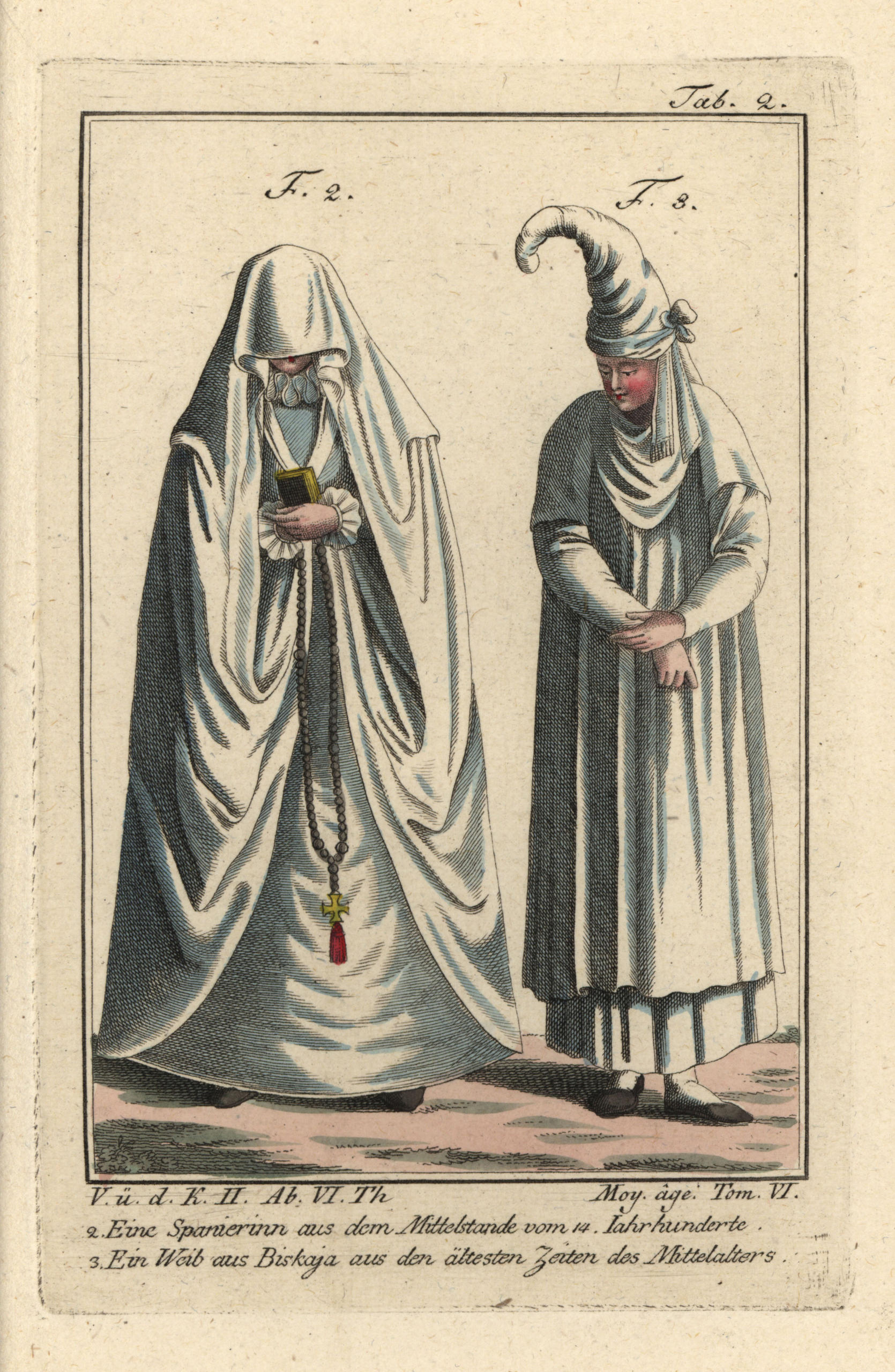

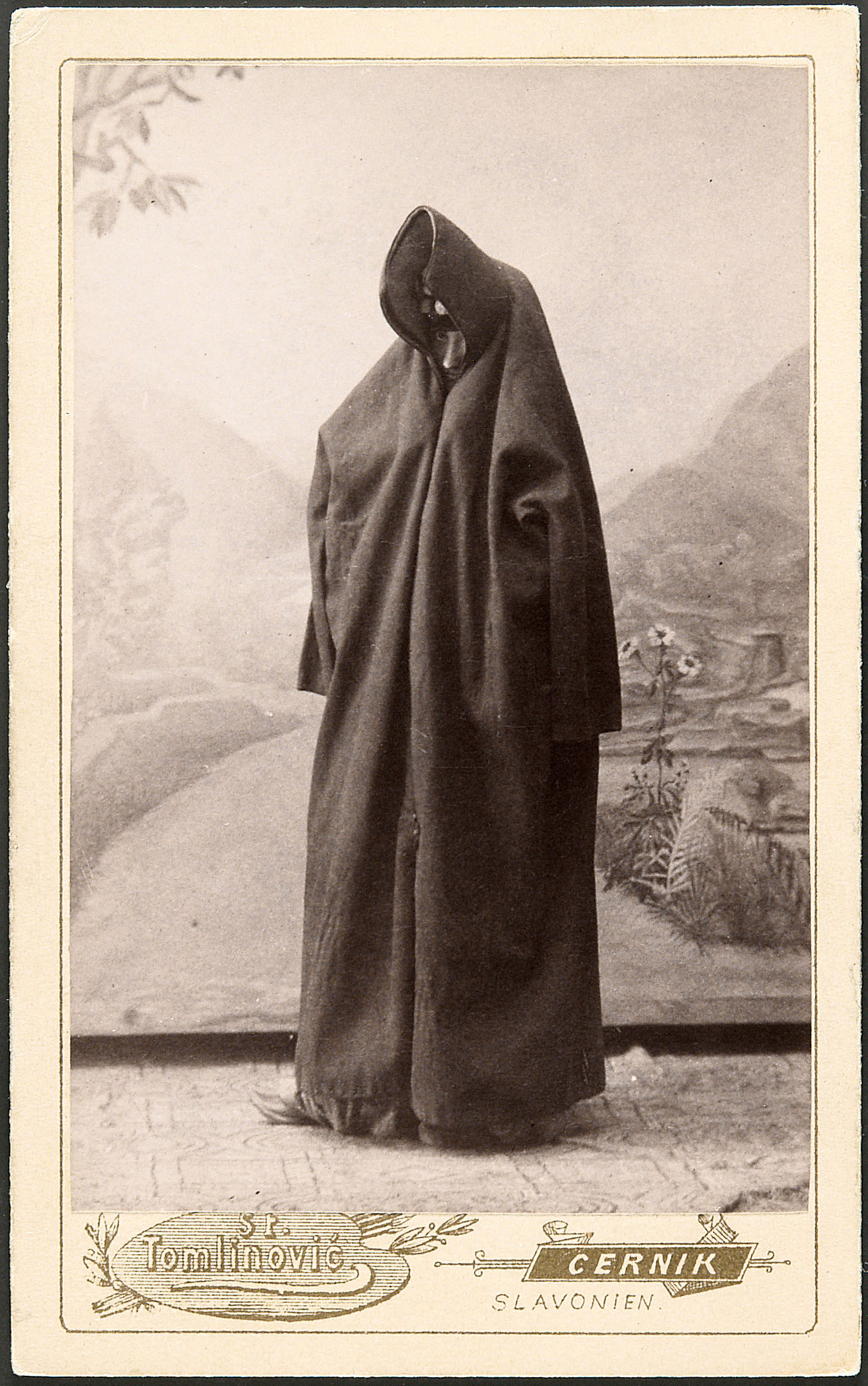

In 2018, the Vienna Weltmuseum addressed different aspects of the veil with the exhibition, Veiled, Unveiled! The Headscarf’. The collection illustrated many facets of this simple piece of cloth which continues to divide opinion and schools of thought. Its carefully crafted catalogue brought together curious examples of the veil throughout the centuries.

‘Veiled, Unveiled! The Headscarf, Vienna Weltmuseum

Before the exhibition in Vienna, Susanna Burghartz, professor of Renaissance and Early Modern History at the University of Basel, had already approached the subject through a cultural-historical perspective, resulting in the essay “Covered Women? Veiling in Early Modern Europe” (2016).

In light of the recent vote in Switzerland, SWI swissinfo.ch asked Burghartz to shed light on the veil and its significance. After all, the symbolism inherent in the debates has not been resolved with the result at the polls.

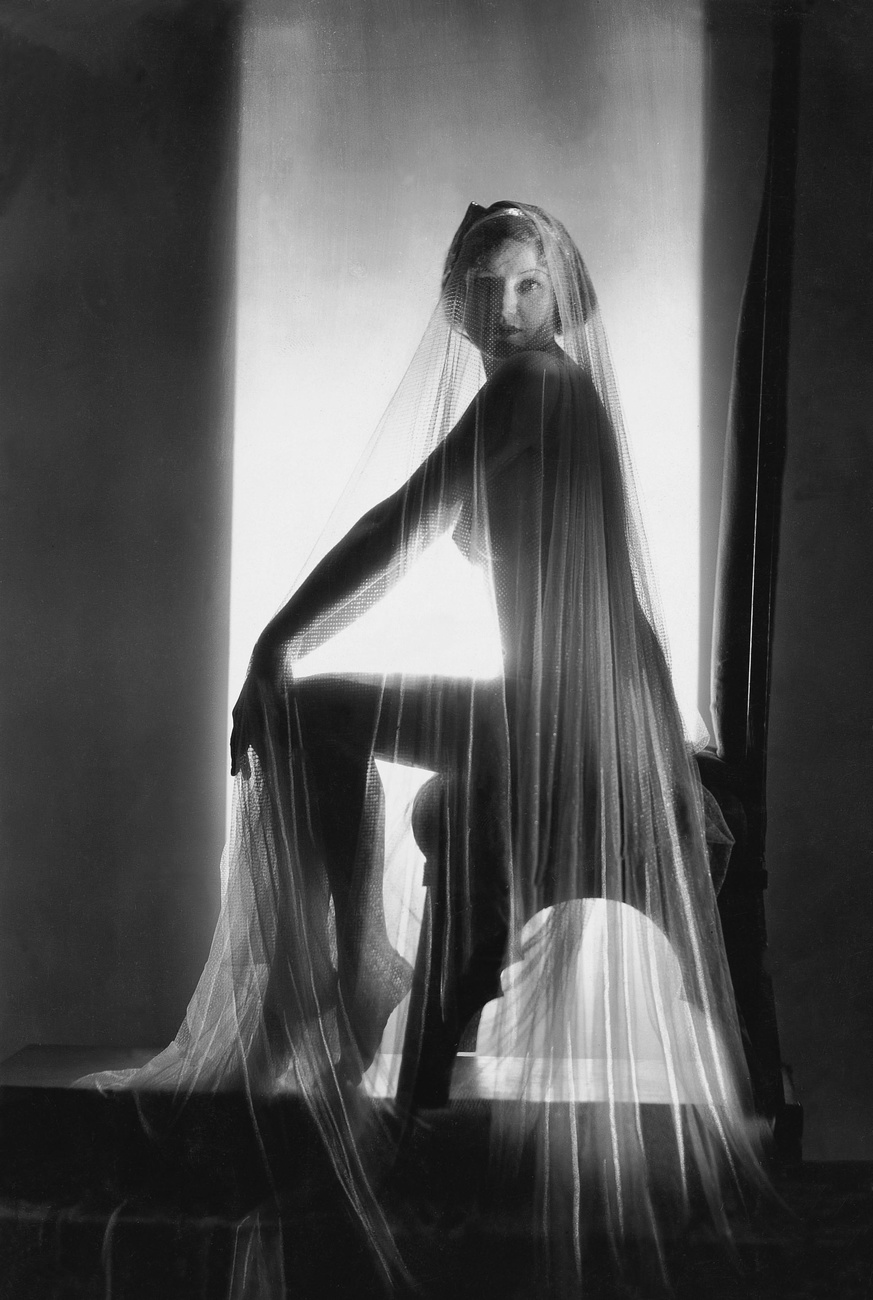

For a start, Burghartz shows that women’s “liberation” from covering up in the West was not straightforward, and that the historical development of “unveiling” women was not a linear process. Emptied of its religious aspects, even in the secular world, she says, “its subjection to the vagaries of fashion was by no means a sign that the veil had entirely lost its meaning”.

SWI swissinfo.ch: How do you view the transformation of the headscarf and veil from the issue of morality, religion, and sexuality to the political dispute we see today?

Susanna Burghartz: Dress in general, and especially headscarves and veils for women, were and are still, often charged with far-reaching cultural meanings that have been and continue to be used politically. For example, clerics in various cultures have declared headscarves and veils to be objects of morality. Time and again, the headscarf and veil have been styled as issues of power through which certain groups can gauge their influence (for example, the clergy in Basel around 1700, or in Iran today).

SWI swissinfo.ch : Does this mean that those wearing such coverings were and are only concerned with the political implications of their dress?

S.B.: Not at all. Coverings can also offer protection, while revelation can expose. In recent years, the headscarf and veil have increasingly been used as a conspicuous symbol of a bitterly fought struggle between “the secularised West” and “Islam”. If we look at the many different veil fashions over the course of history, however, the question arises whether such talk of a “clash of civilisations” doesn’t actually restrict women’s options for action rather than expand them. Accordingly, dress codes – whether compulsory or banned – are problematic for a culture that relies on the freedom of choice for individuals.

SWI swissinfo: To what extent have European women fought against ‘body covering’ dress codes, and are there any examples where they made a breakthrough before the 20th century?

S.B.: The history of fashion and regulation is too diverse to be told in a few sentences. However, there are certainly historical examples of women not only being subject to dress regulations, but also developing forms and materials of their clothing themselves, changing them and adapting them to their needs.

The example of the Nuremberg patrician women has become famous. At the beginning of the 16th century, with the help of Archduke Ferdinand, they succeeded in getting rid of their traditional headgear – the elaborate and stiff “sturtz” – against the will of the city councillors. In Spain, on the other hand, women were forbidden to wear the veil at the end of the 16th century because, in the eyes of male critics, they used the so-called “tapado” body veil in an obscene way to seduce men.

SWI swissinfo.ch : Although the veil has been wielded as a symbol of piety and moral righteousness, hasn’t it also created new forms of sensual or sexual codes?

S.B.: I already mentioned the “tapado” as one form of playing with veiling. If we look at the long history of head coverings there are many examples of fashionable forms of veils – whether the “huyk” of the citizen women in the early modern Netherlands, the ambiguous use of the veil by Venetian courtesans who wanted to attract their clients and present themselves as respectable women at the same time, or the new fashion at the end of the 18th century when fashionable women used delicate veils to enhance their attractiveness.

In the West, too, the veil remained fashionable until almost the present day. Fabrics were produced in leading textile regions like northern Italy, around Zurich, or Silesia, for the whole of Europe, as reported by Krünitz, an important encyclopaedia at the beginning of the 19th century. Famous women like the Princess of Monaco, or widows like Jackie Kennedy, used such veils well into the 20th century. It was only in recent years that the compulsion to unveil took hold in the West and almost completely supplanted the use of coverings.

Prof. Dr. Susanna Burghartz, author of “Covered Women? Veiling in Early Modern Europe” (2016). She is Professor of Early Modern History at the Institute for European Global Studies, University of Basel.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!