Taiwan’s fight against digital disinformation

The citizens of the small Asian island state – with government support – are successfully fighting back against fake news. But when they want to help shape the country’s policies through direct democracy, they get blocked, as SWI swissinfo.ch learned during a visit to Taipei.

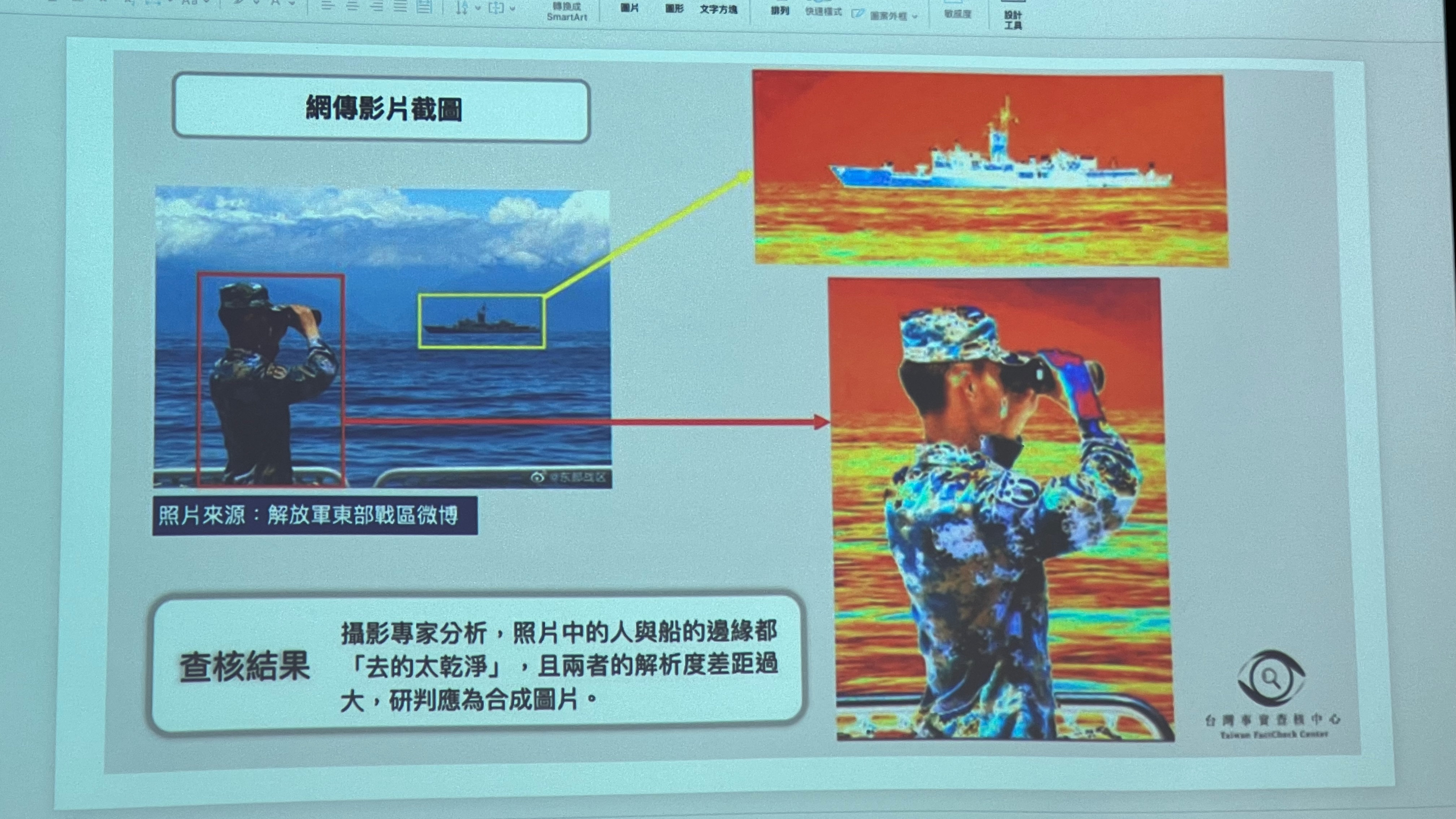

“A naval soldier of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army looks through binoculars to monitor shipping traffic off the east coast of the island of Taiwan,” reads the caption under a press photo, which was published by media outlets around the world in the summer of 2022.

Some media outlets wrongly cited the Associated PressExternal link news agency (AP) as the source, whereas the photo was actually provided to the AP by the Chinese state news agency Xinhua.

Several days later, AP announced that it could see no problem with the picture, but neither could it authenticate it, as “it was not taken by us”.

Xinhua News Agency published the picture to coincide with the conclusion of a visit to Taiwan by the then-speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi.

The press photo was a montage

“But it was a photomontage,” says Eve Chiu. Chiu heads the Taiwan Fact Check Centre (TFC), a non-governmental organisation founded six years ago by media professionals to debunk disinformation.

At TFC, several dozen journalists work around the clock to analyse agency reports and posts published on third-party platforms in Taiwan. They receive tips from users and send alerts to public authorities and media companies, whenever content is found to be fake.

And the organisation’s efforts are bearing fruit, as the case of the Xinhua photo shows. “Using image and sun angle analyses, we were able to prove beyond doubt that the picture of the Chinese naval soldier off the east coast of Taiwan had been manipulated,” Chiu says.

Unlike in Taiwan, awareness of and work on disinformation is still in its infancy in Switzerland. According to a recent report by the Research Centre for the Public Sphere and Society External linkof the University of Zurich, “disinformation has not (yet) caused any major problems in Switzerland. However, recent developments show that this could change at any time.”

A study by the Federal Statistical Office from autumn 2023 shows that the Swiss population’s awareness of the problem of disinformation has increased in the last two years.

However, in view of international experience – including that of Taiwan – the Zurich researchers urge the authorities to examine a comprehensive catalogue of measures, including the “impact of European regulations”, “transparency requirements” and a “labelling obligation for automated accounts”, so-called bots, which are already very active in the case of Taiwan.

TFC is just one of several dozen professional organisations in Taiwan tackling widespread disinformation in the digital space. They have their work cut out for them. According to a comparative study by the global research network Varieties of Democracy, based in Gothenburg, Sweden, Taiwan is now the “country most affected by foreign disinformation efforts”.

More

Explainer: Why Taiwan’s vote commands global attention

The reason for this lies in history and geopolitics: the neighbouring People’s Republic of China has laid claim to Taiwan since it was founded in 1949.

Added to this is the economic importance of the 16th-largest trading nation, which – as Zurich sinologist Simona Grano put it in an interview with SWI swissinfo.ch earlier this year – is “at the centre of the global supply chain and maritime trade routes”. So here, too, the country is in direct competition with China.

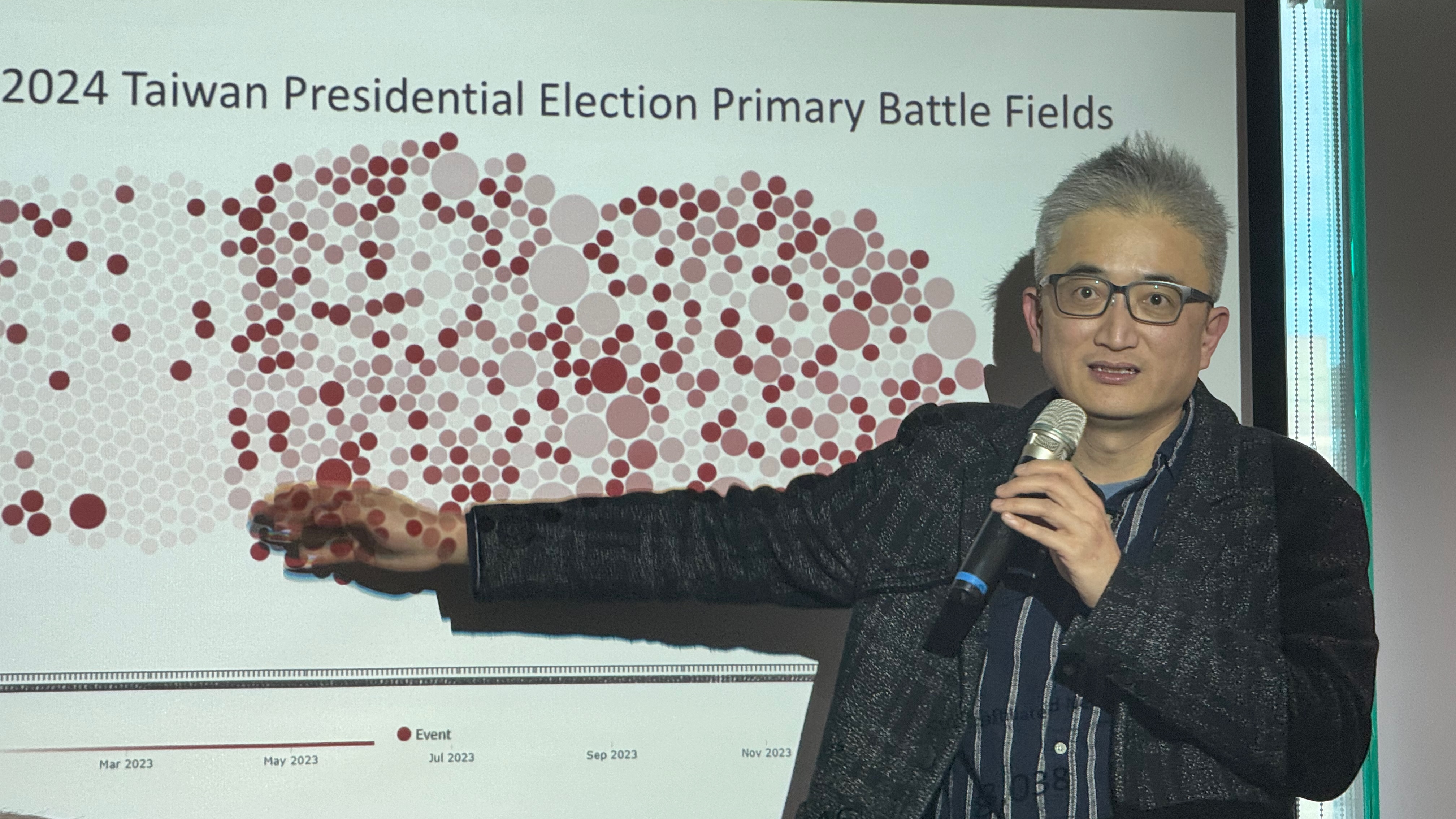

Taiwan’s 2024 Election campaign flooded with deepfake videos

The extent of the problem was again manifest over the past months. In connection with the presidential and parliamentary elections in January and the worst earthquake to strike the island in 25 years in April, Taiwan was “flooded with automated bots on social media and so-called deepfake videos”, says Ethan Tu, founder of Taiwan AI Labs.

Tu and his team “identified and reported hundreds of automated accounts and thousands of manipulated videos”, the former Microsoft and ChatGPT developer says.

On the morning of April 3, a magnitude 7.4 earthquake struck eastern Taiwan. It was the strongest to hit the island since autumn 1999, when a magnitude 7.7 quake caused widespread destruction and thousands of deaths. This time, not least thanks to stricter building regulations and expanded digital warning systems, there was much less damage to infrastructure and buildings. A total of 13 fatalities were reported.

Nevertheless, the natural disaster sparked a flurry of false information on social media, designed to “undermine confidence in the authorities and rescue workers”, as the Taiwan Fact Check Centre (TFC) noted in an analysisExternal link. The false reports, which also found their way into mainstream media, included a manipulated video of the destruction of an iconic rock on an island off the east coast and incorrectly attributed pictures of earthquakes from other parts of the world.

The TFC analysis also illustrates how disinformation attempts differ within Taiwan and abroad, as “in Taiwan, the public quickly sees through false reports that are too obvious”. As a special service after the earthquake, TFC developed an “image verification mapExternal link”, which could be used to check the veracity of published photos from the affected area.

As Tu explains, Taiwan AI Labs managed to group the narratives of these accounts using artificial intelligence (AI). They found that “they largely represent the line of the Chinese state media and highlight the strength of the Chinese armed forces.” There is therefore little point, Tu adds, in checking the facts of the AI-manipulated content: “Instead, we must expose the sheer scale of the disinformation,” he says.

The small island state has been successful in this. In the Bertelsmann Foundation’s latest report on levels of development of democracy and market economy, Taiwan ranks first out of 137 countries worldwide.

More

Does social media fuel fake news in Switzerland as much as in the US?

What Switzerland can learn from Taiwan

“We can learn a lot from Taiwan,” says Daniel Vogler, the deputy director of the Research Centre for the Public Sphere and Society at the University of Zurich. He is the co-editor of a new report, Governance of Disinformation in Digitalised Public Spheres.

While restrictions and bans on certain media and social platforms are increasingly being considered and adopted in Europe and the United States, the Taiwanese authorities have so far deliberately refrained from taking such steps. “In Switzerland, too, we are rather sceptical about frameworks such as the EU’s Digital Services Act (DAS) to regulate the major internet platforms,” says Vogler.

The DAS holds online platforms accountable when it comes to the dissemination of information by users. “Every country and every society has its own particularities, which should be taken into account when dealing with digitalised media,” Vogler stresses.

For Switzerland, which Vogler says is still comparatively less affected by disinformation campaigns, the University of Zurich researchers formulated a list of possible measures in their report, including an “independent disinformation monitoring body”.

Audrey Tang’s unfulfilled promise

In recent years, Audrey Tang has played a key role in the public perception of a “democratic” response to digital challenges. Since 2016, Tang has worked first as a minister without portfolio, and from 2022 as digital minister – in her own words not for but with the governmentExternal link in Taipei. She sees herself as a direct link between the country’s rulers and civil society.

Now, with the arrival of the new government of President Lai Ching-te, elected in January, Tang’s stint of “co-working with the government” will be over in late May.

The elections earlier this year clearly illustrated how Taiwan still relies on analogue methods for important, formal decision-making processes.

The nearly 20 million eligible voters were only able to participate for eight hours at an assigned polling station in their home municipality. The same evening, each completed ballot paper was held up and declared individually, giving interested members of the public the chance to verify every single vote cast.

And even before the last ballots had been counted, the major parties’ front-runners were already congratulating each other. This is also how democracy works in the 21st century on the Ilha Formosa, or beautiful island, as Taiwan was once called by Portuguese sailors.

While Taiwanese citizens have played a successful role in combating disinformation, a second “democratic promise” made by Tang and the government of former President Tsai Ing-wen has not been fulfilled.

“So far, little has come of the long-announced digital participation of citizens in politics,” says professor Yen-Tu Su. Su heads the law department of Academica Sinica in Taipei and describes the government’s approach to citizen participation as “contradictory to say the least”. In 2018, parliament passed a far-reaching reform of direct democratic people’s rights.

Reform on citizen participation backslides

The reform included the introduction of a system for collecting electronic signatures for initiatives and referendums. “But nothing has come of it so far,” says Su. On the contrary, parliament has recently further restricted proactive citizen participation with new hurdles, and Su today sees “little interest” among political decision-makers in changing this. Their focus is now on warding off external threats.

The Taiwanese path to digital participation thus remains primarily reactive. “Our social commitment to defending our hard-won democratic freedoms also stems from our own authoritarian past and the current government in China,” says Chihhao Yu, co-director of the Taiwan Information Environment Research Centre, a non-governmental organisation working at the interface of the struggle against disinformation and media education. As Yu concludes, “we are a young democracy, and in the current tense world situation large swaths of society are aware that each and every one of us bears a responsibility for freedom.”

Edited by Mark Livingston/adapted from German by Julia Bassam/gw

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.