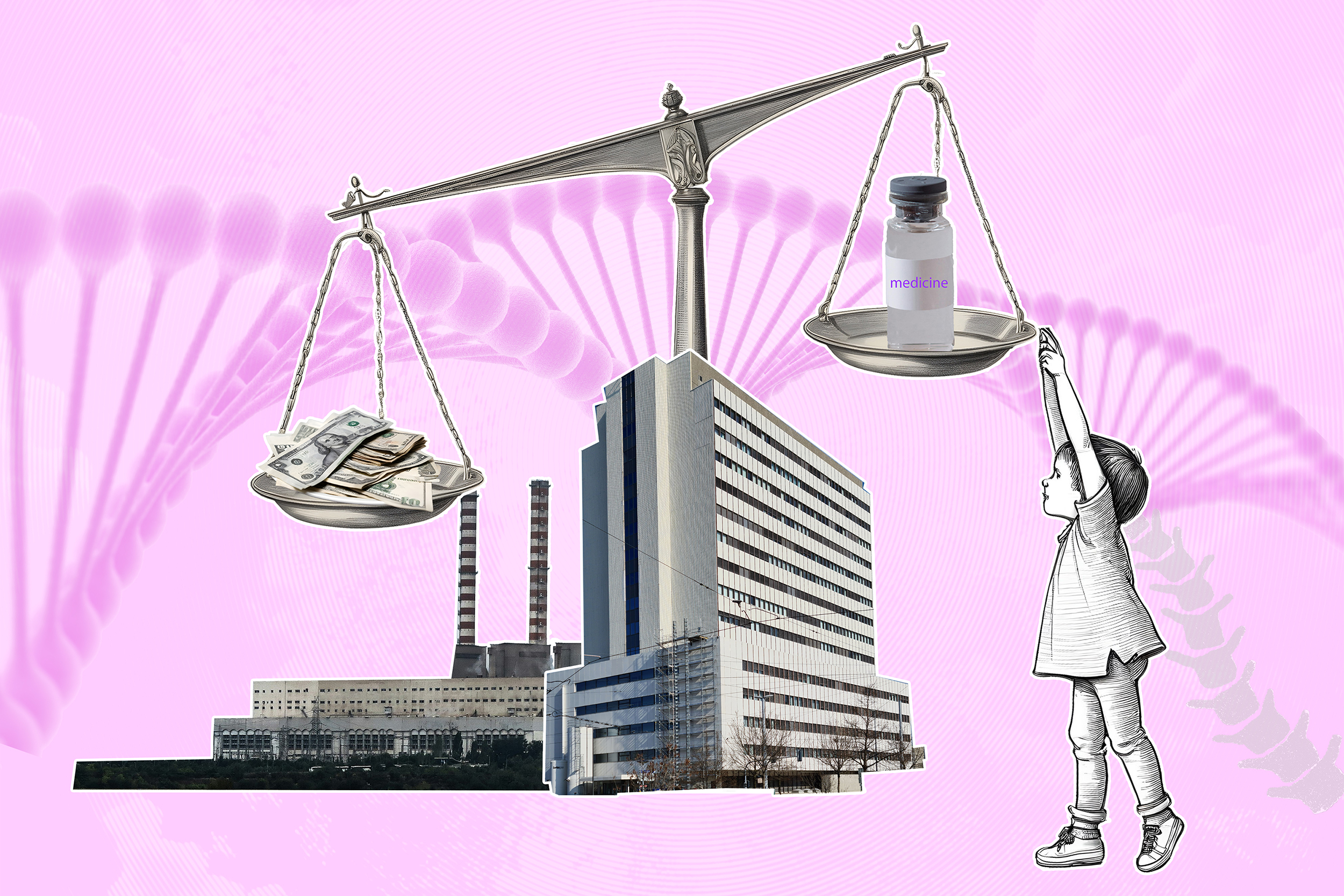

Turkey vs. Zolgensma: the battle over a $2.1 million drug

Families in Turkey have waited years for the government to approve Zolgensma, a $2.1 million (CHF1.9 million) gene therapy sold by Swiss pharma group Novartis, to treat a rare and potentially fatal genetic disease in infants. Many desperate parents have turned to crowdfunding to pay for the drug.

Rüzgar has been fighting for his life since the day he was born. At one month old, he was diagnosed with the most severe form of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a rare genetic disease that causes progressive muscle loss. Without treatment, babies who show symptoms before the age of six months typically don’t survive beyond their second birthday.

As soon as Rüzgar’s parents were told he had the disease, they knew what they had to do – they launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise $2.1 million to pay for a gene therapy they believed would save his life: Zolgensma. Although dozens of other countries, including the United States, had already approved the one-time treatment, the Turkish health authorities were holding out, insisting that there was insufficient evidence of the drug’s efficacy to justify its eye-popping price tag and include it on the list of approved medicines.

More

Whatever happened to the world’s most expensive drug?

SMA is more prevalent in Turkey than in most other countries because of the high rate of marriage between relatives. Some estimatesExternal link suggest that one out of 6,000 babies in Turkey is born with SMA compared with one out of 10,000 globally. At least 3,000 infants and adults live with SMA in the country and around 150 new cases a year are diagnosed, mostly in newborn babies, according to Turkish health ministry estimatesExternal link.

Turkish parents watched children with SMA in other countries achieve typical baby milestones such as sitting up and eating on their own after receiving the one-time infusion. Desperate to help their own children, hundreds of parents like Rüzgar’s turned to crowdfunding to pay for the therapy, which is unaffordable for most people in a country where the average annual salary is around $32,000.

“Images of babies were all over Twitter and Instagram. Campaigns appeared on advertising screens in trams with Iban [bank account] numbers along with photos of babies with SMA. It was very emotional,” said Mine Sanem Özkan, a health technology researcher from Turkey, who wrote her Masters thesisExternal link on the challenges of accessing drugs to treat the disease.

SMA is caused by the absence or a mutation in the SMN1 gene, which provides instructions for making the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein. This means little or no SMN protein is made causing motor neurons to become sickly and die, leading to progressive muscle loss.

All individuals with SMA have at least one “backup gene,” known as SMN2. Patients with more copies of this gene tend to have less-severe SMA, and will develop symptoms later in life.

SMA is classified into four clinical types based on age of onset and motor function. Type 1 (unable to sit independently and usually occurs in babies under 6 months); type 2 (able to sit independently but not walk); type 3 (independent walking) and type 4 (independent walking and adult onset). The most common form of SMA which affects 45% to 60% of sufferers is type 1. These infants typically don’t survive past the age of two without significant mechanical ventilatory and nutritional support.

Medical evidence shows that the earlier someone receives treatment, the better they respond. However, SMA is not included in newborn screening in many countries

Politicians were tagged in parents’ tweets and asked to simply retweet. Some campaigners were able to receive a “like” on Facebook or Instagram from a Turkish actor or football star, helping reach more potential supporters.

Families who managed to raise enough money flew to Dubai, Hungary, or the US where their babies could receive the drug. Some patient associations estimate that at least 100 infants went abroad for treatment. Rüzgar was one of them. In September 2020, when he was 14 months old, he and his family travelled to the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio in the US where he received his Zolgensma infusion. A year later, he was able to sit up and stand on his own.

However, some children died waiting for families to raise enough money. Others became ineligible for Zolgensma because they had exceeded the age or weight limit for the drug or their muscle loss was too severe.

Public pressure

The emotional campaigns caused a public outcry that piled pressure on the Turkish government to make Zolgensma available and for the state-funded Social Security Institution (SSI), which provides free healthcare, to reimburse it. But the government refused to budge.

The Ministry of Health had set up a scientific review board in 2020 to assess new treatments for SMA. After a first evaluation of Zolgensma that year, the board concluded that there wasn’t sufficient evidence of the drug’s safety and efficacy to recommend its approval.

When the review board reached the same conclusion in 2021, Health Minister Fahrettin Koca, who chaired the board, warned families not to organise crowdfunding campaigns for a therapy whose touted benefits were not backed up by evidence. And in 2023, when the board stuck to its position for a third time, Koca reiterated that the government “will not allow our children to be used as guinea pigs”.

More

Drug pricing: Swiss expert calls for more transparency

Zolgensma had been approved on a fast-track timeline in the US and Europe to expedite access for patients with few other treatment options. Fewer than 40 patients had been involved in trials prior to US approval, and although many infants were achieving major motor milestones, there was no data on how long the benefits lasted.

“The government never said Zolgensma was too expensive or that it couldn’t afford it,” said Ece Soyer Demir, who founded the first SMA patients association in the country, Turkey SMA FoundationExternal link, in 2017 after her son Çağan was diagnosed with the most severe form of SMA when he was just a few months old. Rather it put the onus on Novartis to provide more evidence.

The ministry also disputed claims by some crowdfunding campaigns that SMA sufferers had no alternative treatment options and would die if they did not receive Zolgensma by the age of two.

The Turkish authorities had already approved and agreed to reimburse another treatment for SMA, Spinraza, sold by US pharma group Biogen. Although it isn’t a gene therapy and there were initially restrictions on eligibility, evidence showed it slows the disease’s progression.

Last March, and again in early 2024, Novartis released more clinical trial results demonstrating Zolgensma’s long-term benefits and safety especially if given before symptoms appear, although studies comparing the different therapies with each other are still lacking.

Science and politics

The ministry’s stance on Zolgensma wasn’t just based on a lack of sufficient scientific evidence, it was also highly political, Özkan said. Crowdfunding campaigns raised questions of fairness and equity that split public opinion.

Demir said that while some patients access treatment through crowdfunding campaigns, others cannot because they live in remote areas or don’t have the technical know-how to run campaigns. Her son was too old to receive Zolgensma by the time it was approved in the US, but he has been treated with Spinraza. “Fair and accessible treatment for everyone” should be the goal, she said.

More

How drug prices are negotiated in Switzerland and beyond

The health minister consistently defended the government’s position and pointed the finger at pharmaceutical companies. “The main issue here is advocating for global pharmaceutical companies by crossing the boundaries of morality and making our state look incapable,” Koca was quotedExternal link as saying in a press releaseExternal link in 2021. In 2023, he struck a similar tone, sayingExternal link that the government would not “allow the hope of our families to be used for commercial purposes”.

Novartis’s marketing approach didn’t help Zolgensma’s cause. Despite the high prevalence of SMA in Turkey, the company didn’t involve Turkish sufferers in any of its clinical trials. Nor did it include Turkey in its early access programme, which provides free doses to some patients in countries where a drug isn’t yet approved.

This contrasted with Biogen which, a public official told Özkan, had “played it by the book”. The company had an agreement with Turkey to provide free doses and had conducted clinical trials in the country before Spinraza was approved.

Swiss pharma group Roche, whose drug Evrysdi was approved by Turkey for inclusion in the treatment guidelinesExternal link for SMA sufferers in 2023, had also included patients from the country in clinical trials. Evrysdi’s list price in the US is $100,000-$340,000 per year depending on the patient’s weight and it must be taken every day for life, in contrast to Zolgensma, which is a one-time intravenous infusion, potentially making Evrysdi a more expensive treatment.

Prevention in place of a cure

A Novartis spokesperson told SWI swissinfo.ch that for reasons of confidentiality, the company couldn’t disclose details of its conversations with the Turkish government, but it regretted that no consensus or agreement had yet been reached with the Turkish health authorities.

In an email he said Novartis remained committed to engaging with Turkish health authorities to identify “flexible, sustainable, and affordable access pathways” for the treatment of eligible SMA patients in Turkey.

Although Zolgensma still isn’t available in Turkey, publicity generated by the crowdfunding campaigns and the political response has led to positive changes, according to SMA advocates. The government has now included the disease in newborn screening, enabling babies to be diagnosed and given approved treatments before symptoms appear.

In 2022, Turkey became one of the few countries to offer carrier screeningExternal link for prospective parents. If either parent carries the genetic mutation, the state insurance programme will cover preimplantation genetic diagnosis – a procedure similar to in-vitro fertilisation – to ensure their baby is SMA-free, making treatment unnecessary.

“The government has realised that it is much cheaper to prevent this disease than to treat it,” Demir said.

Edited by Nerys Avery/vm/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.