Geneva exhibition examines human struggle between war and peace

Is war the future of man? This philosophical question is at the centre of an exhibition on war and peace at the Bodmer Foundation in Geneva, which features priceless manuscripts, books and other documents, including part of Leo Tolstoy's original manuscript for "War and Peace" and a 4,500-year-old peace treaty.

“If this exhibition had been held 30 years ago, it would have been marked by incredible optimism,” writes curator Pierre Hazan in the exhibition’s catalogue. “However, three decades on, there has been a brutal change of perspective.”

You only have to follow the daily news to realise this; the United Nations Security Council remains paralysed by conflicts involving the world’s major powers in the Middle East and in the Persian Gulf. The UN has also been sidelined in southern Asia, where tensions are again on the rise in the Kashmir region between India and Pakistan, both of which possess nuclear weapons.

“Man’s responsibility to decide between war and peace is more real than ever,” says Hazan, who works as an advisor to the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, a private Geneva-based organisation specialising in conflict mediation.

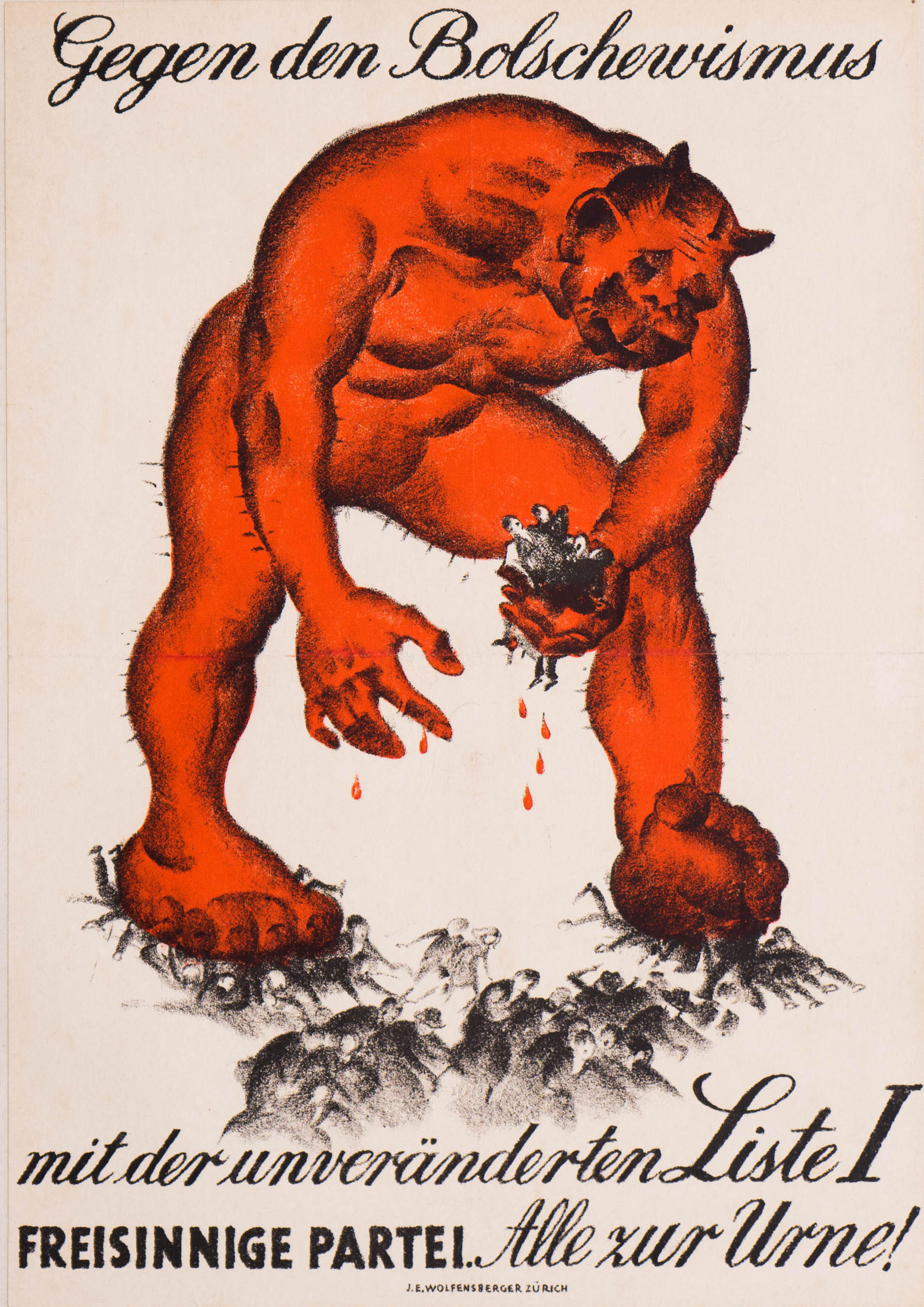

Part of the War and Peace exhibitionExternal link, created by the Bodmer Foundation together with the UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), examines how mass media, starting with radio, has been weaponised as a propaganda tool.

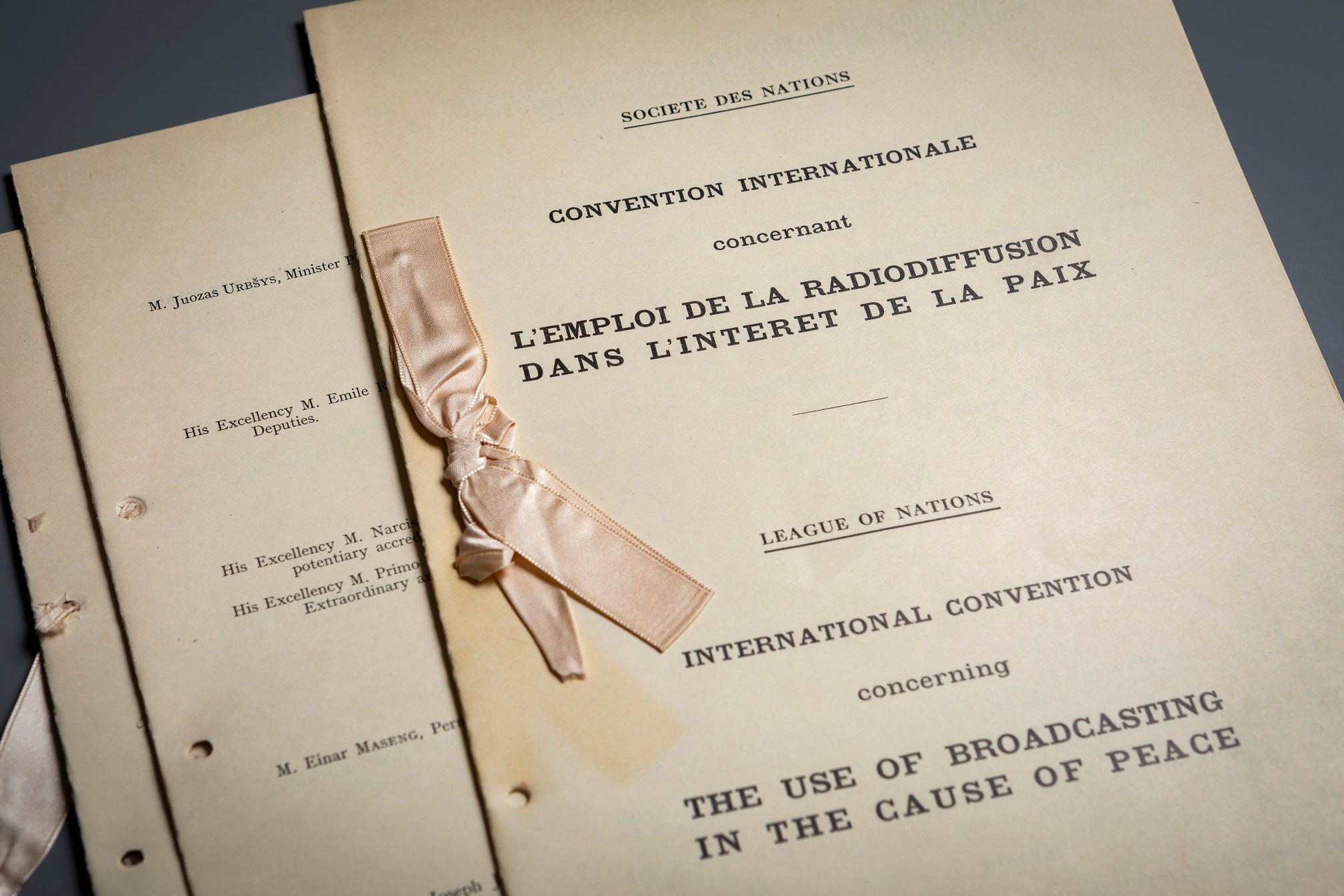

The League of Nations – the forerunner to the UN – tried to combat ideas that fuelled hatred and dehumanised individuals. An International Telecommunications Convention on display in Geneva, drawn up by the League in 1936, urged states to ensure that, in the cause of peace, programmes broadcast from their territories “do not incite war” or encourage “acts which are susceptible to lead to it”.

The 20 nations that signed the treaty also committed to put an immediate end to any programmes “likely to harm good international goodwill via allegations, the inaccuracy of which, would or should be known by the people responsible for the programme”. Today, the UN still struggles to combat the diffusion of hate speech and false information on social networks.

The Bodmer exhibition presents the most extreme example of manipulation from the last century: a copy of Mein Kampf, the anti-Semitic manifesto written by Adolf Hitler and published for the first time in 1925. This is featured alongside a reproduction of the secret map showing the division of Poland by a single pencil stroke that accompanied the 1939 non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Other exhibits reveal the human consequences of war, such as a copy of the original edition of “The Diary of A Young Girl” by Anne Frank, the Jewish teenager who died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. The book is displayed alongside a diplomatic note written in December 1942 by the Polish government in exile to the 26 allied governments entitled: “The mass extermination of Jews in Poland occupied by Nazi Germany”.

Yes, the Allies knew about it, but did nothing until the end of the war. The ICRC, a sponsor of the exhibition, at the time also closed its eyes to the reality of the Holocaust, pursuing a policy of accommodation towards Berlin, which had been adopted by the Swiss government. Discussions took place within the Geneva-based humanitarian organisation whether to publicly denounce abuses against civilians and a vague, measured statement was drafted. But the ICRC eventually dropped it, as the exhibition reveals, highlighting the role of Swiss president and ICRC member Philipp Etter.

Curated by Pierre Hazan and the head of the Martin Bodmer Foundation, Jacques Berchtold, the exhibition doesn’t hesitate to examine such questions. It comes at a time when Antisemitism is once again on the rise, also in Germany. But rather than a being a call to activism, the exhibition invites the visitor to reflect on our long history, and the few lessons we seem to have learned, both in the past and today.

‘Is history cyclical?’ ask the curators. Perhaps. But within this eternal circle there certainly exists a desire for reconciliation.

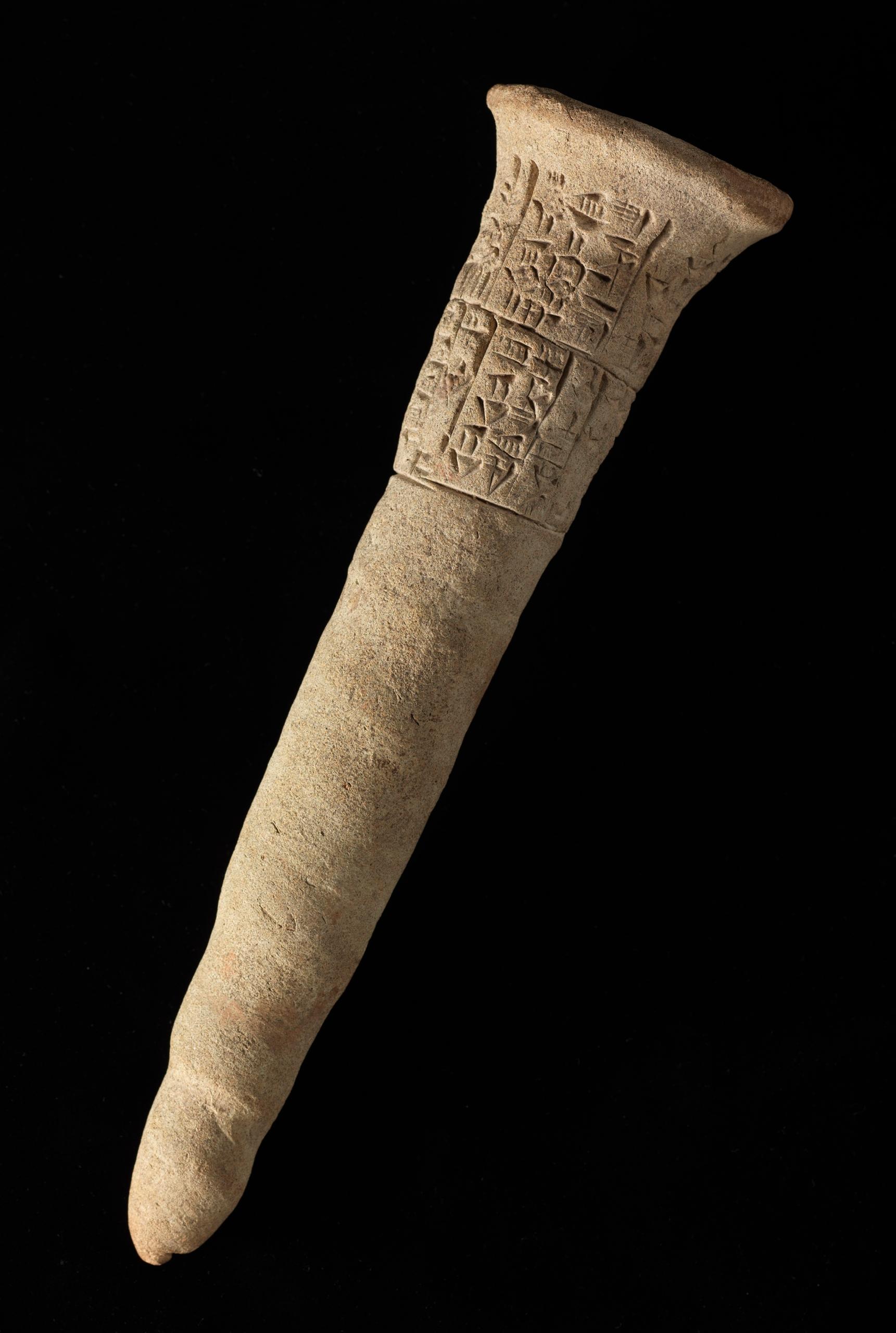

On display is a rare 4,400-year old clay peg from the Sumerian period inscribed with a treaty of peace and friendship in cuneiform. It represents the most ancient diplomatic text in existence.

Also on show is the “Perpetual Peace” treaty, signed in 1516 between the Swiss Confederacy and France following the defeat of the Swiss at the Battle of Marignano, near Milan, Italy. At the bottom of the large parchment, the seal of the French King François 1st is followed by 18 others – representing the 13 cantons of the former Confederation and their allies.

The three main Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – have attempted to define the legality of war and violence. As Hazan notes, this is where the origins of the ‘just war’ can be found, an ambiguous concept that was revived in the 1990s during the Balkans conflicts and the first Gulf War.

In this respect, the Geneva Conventions, devised by the ICRC, were a significant leap forward. They were conceived to enable assistance to be given to the injured, and the protection of prisoners of war and of civilians, regardless of which side they are on. But the exhibition also recalls their initial limitations.

Gustave Moynier, an ICRC founding father, writes in the organisation’s bulletin in 1880 that it is undesirable for African states to sign up to the convention “because the black people of Africa are, for the most part, still too savage to be able to associate with the humanitarian thinking that inspired this treaty and to put it into practice”. The unique exception was the state of Congo, which Moynier helped create; its sole owner, Léopold II, King of the Belgians, ruled the country with an iron fist, bringing about the violent deaths of millions of its people and an international scandal.

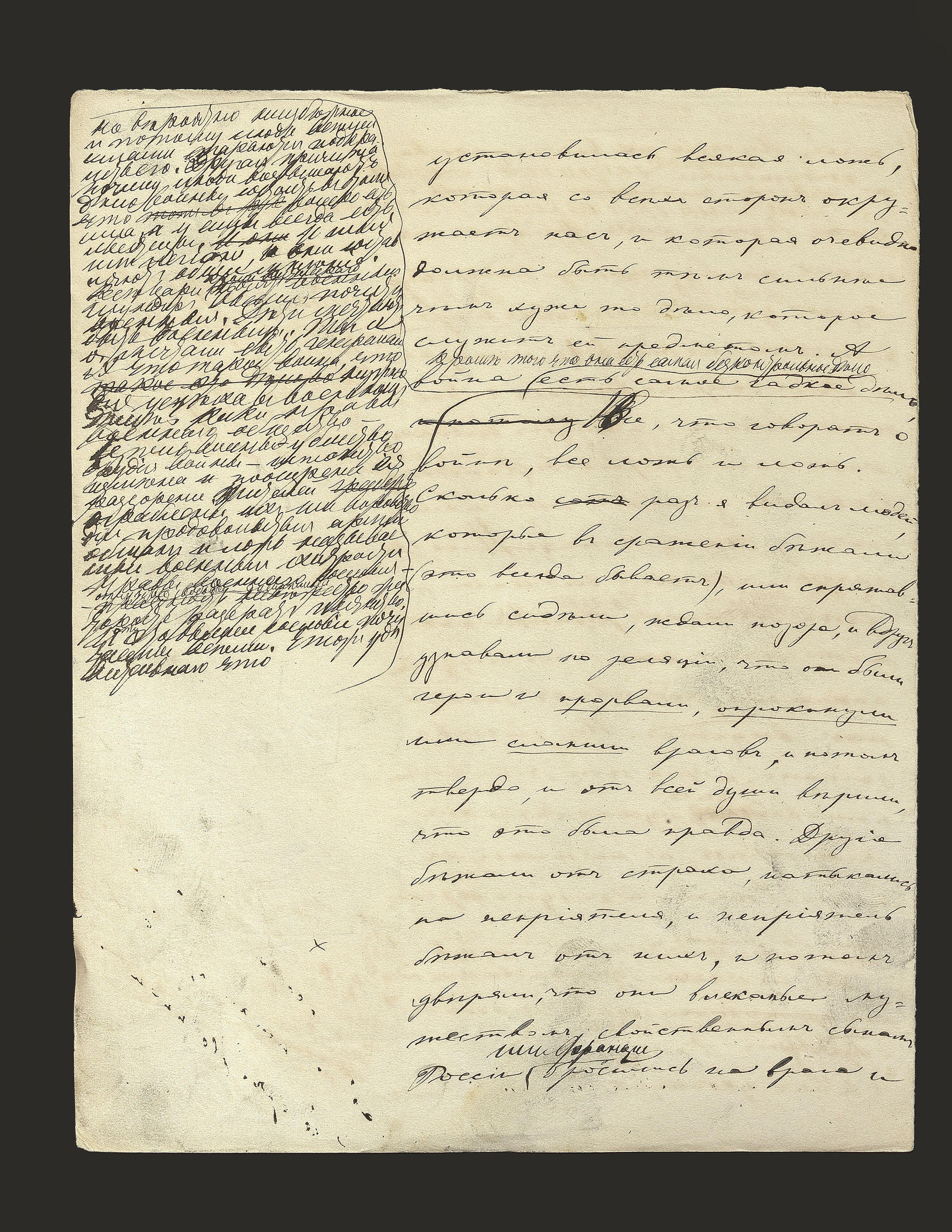

Amid the endless cycle of conflicts and peace accords, several writers stand out who were capable of revealing the lies of war and of reminding us of our human condition. The exhibition features several pages of Leo Tolstoy’s original manuscript for “War and Peace”, which was allowed to leave the Tolstoy Museum in Moscow, Russia, under heavy security for the first time since he wrote the book in the 1860s.

Next to the precious manuscript are classic examples of military strategy, including On War by Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1833) and the Art of War by the Chinese general Sun Tzu (5th century BC).

The exhibition also features an edition of the French newspaper Combat from August 8, 1945, with an editorial by the writer Albert Camus. The future winner of the Nobel Prize for literature comments on the atomic destruction of Hiroshima. And his warning remains true today: “Mechanical civilisation has reached its final degree of savagery. A choice is going to have to be made, in a more or less near future, between collective suicide and the intelligent use of scientific conquests”.

War and Peace

The exhibition War and PeaceExternal link at the Martin Bodmer Foundation runs until March 1, 2020.

It is part of 100 Years of Multilateralism, a series of eventsExternal link organised to mark the centenary of the League of Nations. A parallel exhibition, 100 Years of Multilateralism in GenevaExternal link, is currently on display at the UN Museum at the UN headquarters in Geneva. It presents unique documents from the UN archives, and explores the evolution of the multilateral system since the creation of the League of Nations to the work of the United Nations today.

SwitzerlandExternal link is actively supporting these centenary events.

Translated from French by Sophie Douez

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.