Are Switzerland’s pensions too high?

The Swiss pension system is in danger of collapse. At the same time, Swiss retirees get higher pensions than almost anywhere else in the world. Is the country due for a reality check?

The Swiss are a nation of happy pensioners. A study by UBS (International Pension Gap IndexExternal link) found that in Switzerland (compared with 12 other countries), generous pensions mean that people must save the least for their old age – and that is in a country that hast the highest cost of living in the world.

Anyone in Switzerland who has been a full-time employee for their whole working life can look forward to a comfortable retirement.

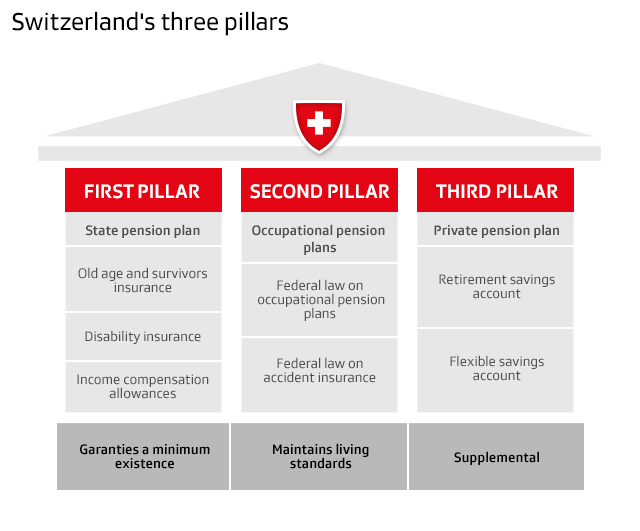

Switzerland has a sophisticated pension system, which is based on three strands or ingredients.

The state old-age pension provides a basic minimum pension for all. Workers also have to belong to a employer-sponsored pension fund, which is designed to maintain their existing standard of living beyond retirement.

The third strand is voluntary saving by individuals, which is encouraged by tax breaks.

Spreading the risk

“Switzerland has always been a model for other countries with its three strands of old-age security,” says Thomas GächterExternal link, professor of social insurance law at the University of Zurich.

“The model is great, but it has never been completed.” Government invests too little in the first strand, he points out, so that the basic old-age pension no longer enables anyone in Switzerland to get by.

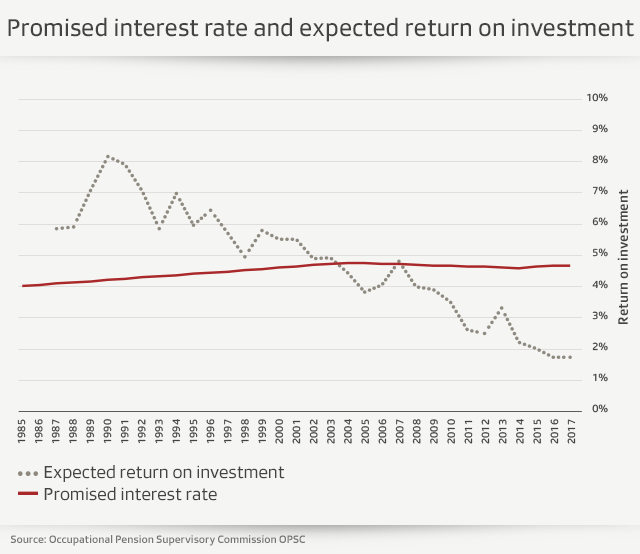

The second strand, private pension funds, is being hampered all the time by low interest rates: if the invested capital brings little in the way of returns, the promised pensions cannot be paid for. There are funding gaps.

Demographic developments are making the problem bigger, especially as regards the government’s basic pension.

A large generation of baby-boomers is now reaching pensionable age. A majority of Swiss now take early retirement, and life expectancy is among the highest in the world. “So the time-bomb is ticking away,” Gächter concludes.

It’s ticking not just in Switzerland, of course, but in many industrial countries.

“Other countries will be hit first,” Gächter expects. Thanks to the three independently-funded strands, Switzerland has spread the risk, which Gächter regards as an advantage. But even in Switzerland there will be problems eventually.

What is the conversion rate?

The term conversion rate means the rate at which invested capital is calculated as an annual pension – given the statistics of life expectancy and expected interest earnings on the capital (return on investment in capital markets). If for example a person has saved a capital of CHF 100,000, with a conversion rate of 6.8%, that person gets an annual pension of CHF 6,800. Changes in the conversion rate only affect future pensions.

Pensions are too high

The first dark clouds have in fact begun to appear over Switzerland as the “pensioner’s paradise”. Some of the private pension funds have lowered their conversion rate, which means reduced pensions for future generations.

Such corrective measures are needed, for the pension funds in recent years have being paying out at an unsustainable rate – and current pensions cannot be changed. “Over several years, the conversion rates used were too high,” says Gächter.

“One generation – the most recent groups who have been retiring – will be getting more for the rest of their lives than they ever paid in.”

Generation X will be the loser generation, he says.

“They have paid in plenty, but they won’t get as much back. They have helped to fund the pensions of the older generation.”

Calls for variable pensions

In the private pension funds, there is still an involuntary redistribution going on involving millions of francs from the working population and the employers to current pensioners. On average this amounts to over CHF7 billion annually, or about 25% of pensions. In this contributory pension system, unlike the government’s old-age pension, there should actually be no redistribution.

Since April, a committee has been gathering signatures for a people’s initiative called “Old age security – keep it fair. For reform that does justice to all generations”.

It was launched by pensioner Josef Bachmann. He used to be CEO of a private pension fund.

The initiative calls for variable pension fund payouts depending on return on investment, so that there need be no redistribution from workers to the pension-age generation. What this means is: if things go well on the stock exchange, you get a higher pension – if things go badly, you get a reduced amount.

Also entering into the calculation would be demographics and the cost of living. Already retired people could see their pensions reduced – and for Switzerland, that would be completely new. “The basic idea of variable pensions is the acceptance that pensions cannot be fixed in advance,” says Bachmann.

Having fixed pensions always leads to redistribution, with younger generations picking up the tab. “This injustice has got to a stage where it’s crying out for something to be done.”

Old folks rule?

The initiative has a bit of a disadvantage: in nationwide votes of this kind, usually more older people vote than young people – not just because of demographics, but also low voter turnout among youth.

Bachmann remains optimistic, however: “The proposal has a good chance of being carried, if many seniors go for it. Old people too can have a clear mind and a big heart.”

More

Social security and Swiss pension system

Adapted from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.