Why Caesar was wrong about the ‘nomadic trouble-making’ Helvetii

Migration, identity, borders – these issues characterised Europe more than 2,000 years ago. The Helvetii, described by the Romans as nomadic troublemakers, are now being cast in a new light: they were in fact both well connected and sedentary.

For Julius Caesar, the Helvetii were the great troublemakers of Europe. In his report on the Gallic Wars, the Roman general describes them as a pugnacious, restless people who left their homeland due to lack of space and set off across half of Europe.

According to Caesar, the Helvetii wanted to leave their land between the Rhine, Jura and Rhone because it had become too cramped and because they “longed for conquest”.

The Helvetii were a Celtic tribe that lived mainly on the Swiss Plateau. The name “Helvetii” is still closely associated with Switzerland, whose Latin name “Confoederatio Helvetica” is a reminder of its Celtic past.

We’re in the late Iron Age, around 50 years before the birth of Christ. Central Europe is a mosaic of forests, settlements and trade routes. The border ran between the advanced world of the Mediterranean and the wild landscapes of the north. The Helvetii lived right in the middle of it all, caught between the Germanic tribes in the north and the expanding Rome in the south.

Myth and reality

However, we know far less about the Helvetii than the myths suggest. Like other Celts, they wrote nothing down, at least nothing that would survive. All the historical sources come from the Romans. This image still characterises the idea of the “wandering Celts” today.

However, where words are missing, traces in the ground speak for themselves: graves, coins, tools, weapons, cult sites. There are numerous Celtic finds in Switzerland, such as the burial ground at Münsingen in canton Bern with more than 250 graves, the sacrificial site at Mormont in canton Vaud with hundreds of animal sacrifices, the Basel-Gasfabrik settlement with trade links across the Rhine, and the finds at La Tène on Lake Neuchâtel, which gave its name to an entire epoch.

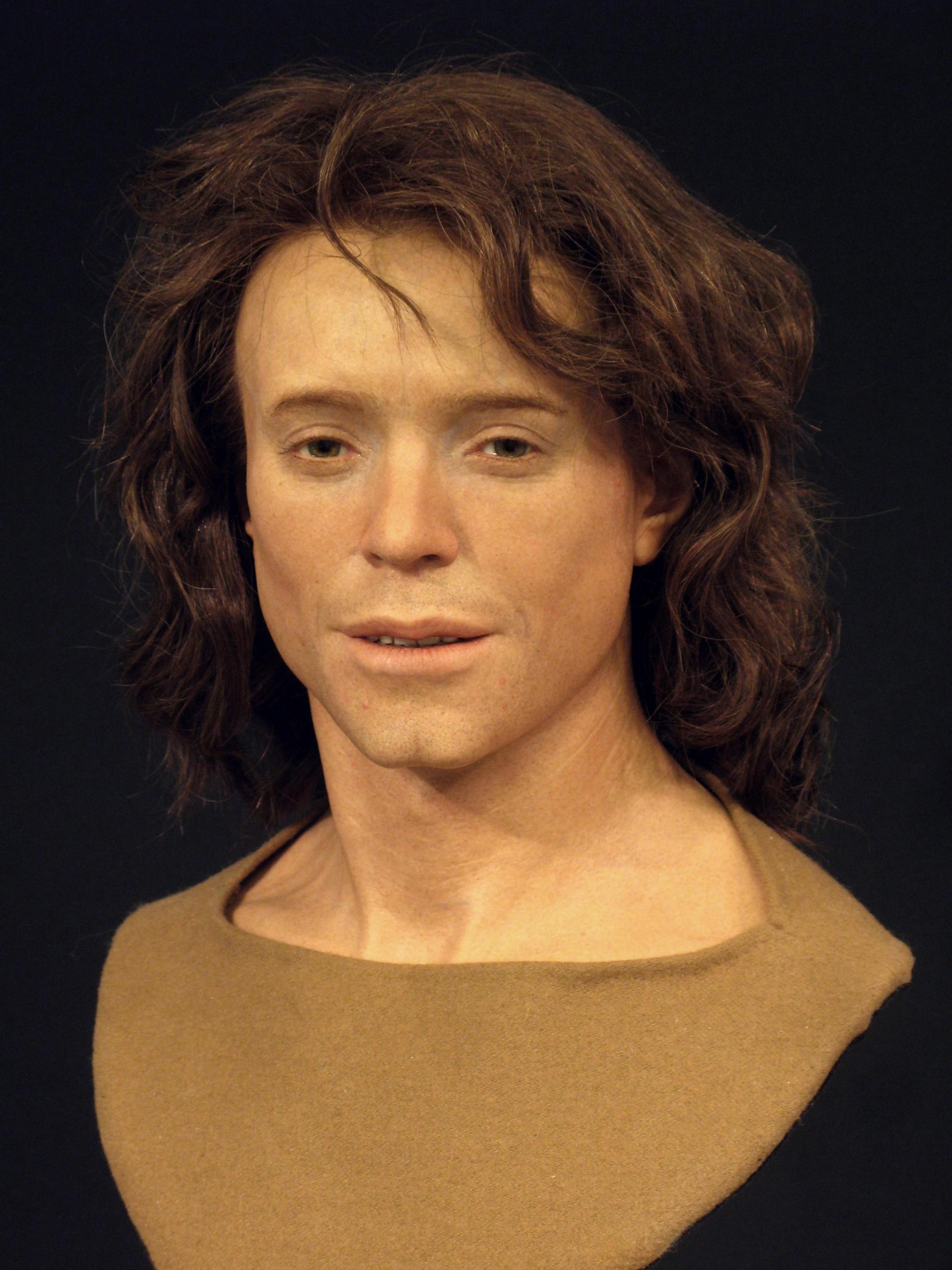

A new look at ancient Helvetian bones

Thanks to new methods, research is now getting ever closer to the Swiss Celts. Marco Milella and Zita Laffranchi are at an exciting point: their Celtudalps projectExternal link – a collaboration between the University of Bern and Eurac Research in Bolzano, Italy – is investigating how mobile Celtic groups were in Switzerland and northern Italy during the late Iron Age.

The two anthropologists, previously at the University of Bern and now at the universities of Pisa (Milella) and Córdoba (Laffranchi), combine archaeological, anthropological, isotopic and genetic analyses in order to visualise migrations, kinship relationships and exchanges across the Alps. The data obtained date from the decades before Caesar’s Helvetian campaign – in other words, from a time before Rome conquered the Alpine world.

“Even then, the Alps were not a border, but a bridge, long before the Romans,” Laffranchi says. “Life was hard, but our data shows that the Alps were a corridor for goods, people and ideas.”

Helvetians: traces of movement

Isotope analyses of teeth and bones reveal where a person lived and died. The chemical signatures of strontium, oxygen and sulphur are a kind of geological fingerprint: they show the composition of soils as well as the climatic influences of the respective region.

The result paints a complex picture: most individuals remained in the same region for their entire lives, rooted in their communities and integrated into local networks. Only a few show clear deviations in their isotope values, which indicate longer journeys or origins from more distant areas.

“We haven’t seen any signs of large-scale migration so far,” says Milella. “Rather individual movements, selective influxes into a stable population. Foreigners are turning up, but not in droves.”

This suggests that the Helvetii were more sedentary than nomadic.

Nevertheless, mobility was part of everyday life: traders, craftsmen and marriage connections linked valleys and settlements to form a dense network. The Helvetii were therefore not restless nomads but networked settlers in the heart of Europe.

Questions about Caesar’s version of events

Much of what Caesar and other Roman writers described – the great migrations and war campaigns of the Helvetii – has yet to be scientifically proven.

Specific aspects of his account also remain questionable. Caesar reports that the Helvetii burned down 12 towns and over 400 villages before travelling west with 368,000 people. They were confronted and defeated by the Romans at Bibracte, in present-day Burgundy.

Caesar mentions 258,000 dead; 110,000 survivors were sent back to Helvetia, where they were to serve as a bulwark against the Germanic tribes. To this day, however, neither traces of burnt Celtic cities nor the battlefield of Bibracte have been found.

According to the researchers, in the long term it would be interesting to compare the Swiss data with data from other Central European regions, such as France. Also later, Roman and early medieval samples could provide valuable points of comparison and show how supposedly historical processes, such as those reported by Caesar, are reflected in biological data – and how the Roman conquest and mixing with the Celts actually took place.

The Celtudalps project is currently in the evaluation phase. “The project funding ran out in May 2024, but we have collected a lot of isotope and genome data,” Milella says. New results are due to be published in 2026.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Adapted from German by DeepL/ts

More

Facing up to Switzerland’s Roman past

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.