Swiss comic art is due for a revival

Comics are a Swiss invention, but the country’s market has always been too small to set itself apart. That may be about to change, thanks to a burgeoning scene in Geneva and the revival of a huge and rare comic book collection that highlights the genre’s rich history in Switzerland.

Cuno Affolter is the guardian of Switzerland’s biggest collection of comics – Europe’s second-largest – and is one of the country’s longest-standing aficionados of the genre, but not just: journalist, critic and curator since the early 1980s, his authority on the subject is uncontested.

“The comic book is an old medium now,” he acknowledges as he opens his treasure trove in the Lausanne municipal library’s underground storage area. It’s piles of comics, new and old, in various languages.

Rare issues of the underground Zap Comix of the late 60s lie in perfect condition beside the very first editions of Tintin. There’s a pirated version of the Belgian hero’s story, called “Tintin in Switzerland”, published in Holland in the 1980s and filled with drug use and sex scenes involving a gay Captain Haddock, a nymphomaniac Bianca Castafiore, and a junky Tintin.

Beside some issues of Mickey Mouse, published in Zurich in 1936, is a folder with a child’s drawings of the Disney character that look a bit out of place. The child, it turns out, was H. R. Giger – the eccentric Swiss Oscar-winning artist who created the set design for the movie “Alien”.

“Alien” would probably never have existed if it weren’t for Mickey Mouse,” Affolter points out.

A comic book enthusiast could easily spend weeks perusing the rarities in Affolter’s collection, which includes another large archive in the neighbouring building. The comics are in temporary storage while a new library is built that will that will house the whole treasure in better, and more visible conditions.

Swiss invention

The comic book was invented in Switzerland – more precisely in late 1820s Geneva, by the pedagogue and politician Rodolphe Töpffer. His satirical “illustrated stories” were simply meant at first to entertain his friends, J.W. Goethe among them. The German poet encouraged Töpffer to publish his inventive designs, bestowing a “godfatherly” blessing on the new genre.

Töpffer even came up with some theoretical principles behind the illustrated stories, based on the effect of mixing text with illustrations.

“The images, without the text, would have just an obscure meaning; the text, without the illustrations, wouldn’t mean anything,” he mused.

More

Cuno Affolter

The format soon became quite popular, especially in Germany, from where a thriving publishing industry of “illustrated stories” rapidly made its way to the United States.

“The modern comic book started in America, in those boulevard newspapers of Hearst and Pulitzer, because it was the first time that millions of people read the same story, throughout the whole country. Then they threw it away, and the next day another story, or a continuation of the day before, would come out, and so on,” says Affolter.

“These early comics were a simple product of consummation, while what Töpffer did was much more like a real book.”

And Affolter acknowledges that the Swiss claim to the comic book actually has a more complex story behind it.

“It’s like how photography came up – we may think that we [the Swiss] invented it, but we also know that, at the same time, it was being developed in other places, such as Japan. So it’s very difficult to say that such person invented it on a certain date.”

New audiences

Having dedicated over 40 years of his life to the genre, Affolter cannot help but see the development of the comics in a broader perspective.

“At the beginning, by the turn of the last century, comics were made for the working class,” he points out, adding that publishers wanted to sell newspapers to people who weren’t in the habit of reading.

Affolter says that when radio emerged in the 1920s and 30s, some comics, like Dick Tracy, were already aimed at young adults. From those, new media formats like television and radio picked up on the “cliffhanger” effect to keep audiences hooked, day after day.

“It set the grounds not just for modern comics, but also for the ways mass media developed narratives with a grip on the audience,” the comic collector notes.

Two Cultures

In Switzerland, comic strips were already very popular in the 1930s, thanks to Globi, a character invented as a marketing prop for Globus department stores. He’s still a hit with children today. But when it comes to the adult segment, massive differences between the French and German-speaking parts of Switzerland emerged along the imaginary cultural dividing line commonly known as the “Röstigraben”.

Swiss-Germans were, for the first half of the last century, very influenced by the German comic scene that died out after the Second World War. While the French kept publishing comics during the Nazi occupation and afterwards, the post-war Germans had more pressing problems to solve. But eventually, the German comic scene came back with a bang, says Cuno, with a new-found style free from prior influence.

More

Anna Sommer

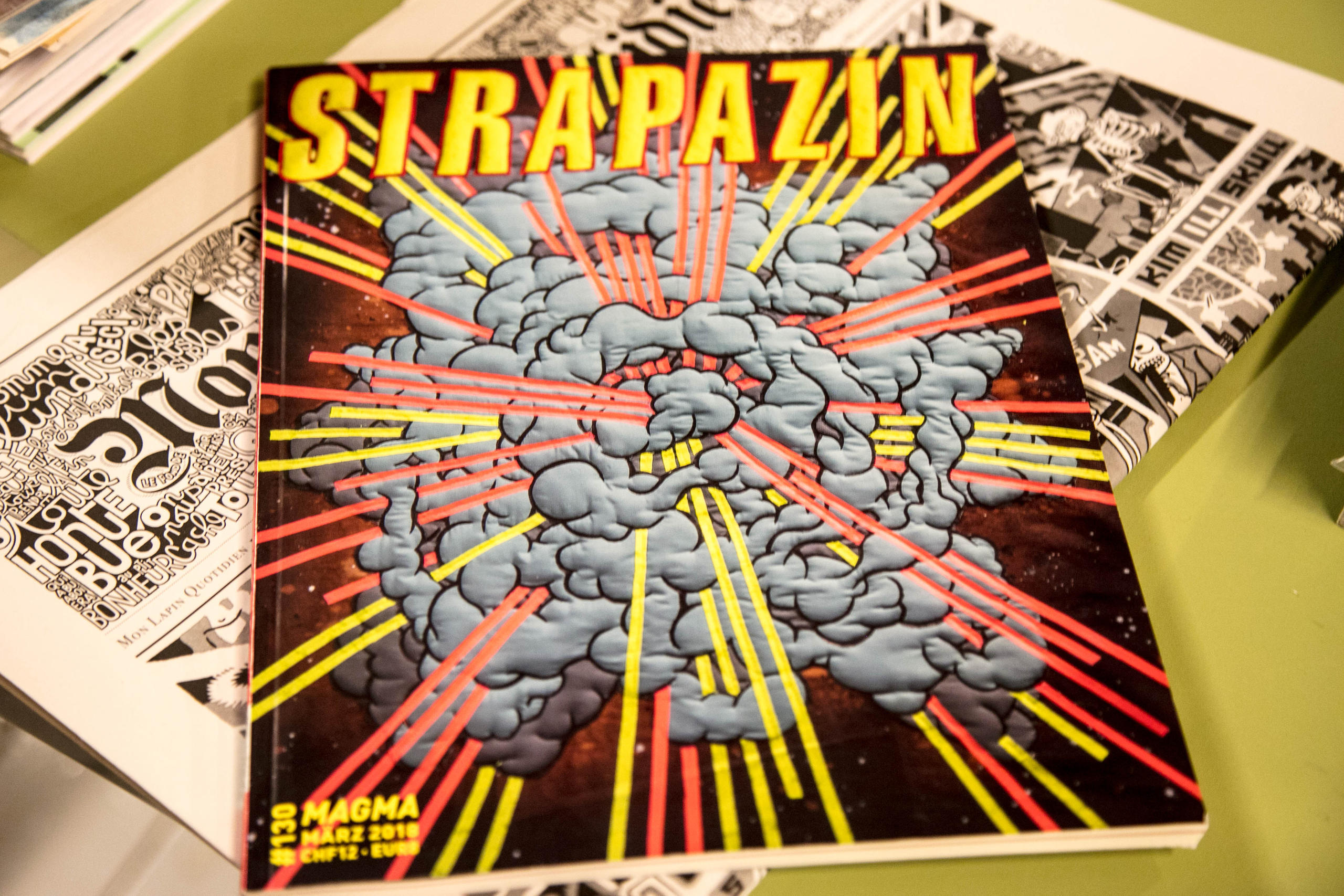

That same blank-slate background gave a new impulse to the scene that flourished in Zurich in the late 1970s and 80s. Magazines emerged such as “Strapazin” – still an important reference for today’s artists – and the large publisher Edition Moderne also contributed. But today, Cuno says the Swiss-German comic scene is plagued by the constraints of a small market and a lack of interest among young people.

More

Thomas Ott – Einfall

Geneva emerges

But the story is completely different in French-speaking Switzerland, which Affolter says was always influenced by the massive comic book market in neighbouring France.

In the 1970s, the French-speaking Swiss artists Derib, Cosey and Ceppi managed to establish a Swiss style, different from that in Paris. These authors were some of the first to bring personal stories into their work such as their experiences living in India as hippies.

But with the lack of an established market for comic books in Switzerland, their success didn’t last long.

Today, however, Cuno sees a comic book scene emerging in Geneva that he thinks has potential. He points out that many young artists are self-publishing their work, creating so-called “fanzines” for fans of a particular performer or group. And the Geneva School of the Arts recently launched a course specifically for comic book creators.

Geneva’s new scene, combined with Affolter’s soon-to-be-displayed comic book collection, means that French-speaking Switzerland could soon become home to the next revolution in Swiss comics.

Fumetto International Comic Festival

This week, Lucerne is hosting the 27th Fumetto festivalExternal link, attracting thousands of comic book enthusiasts, artists and experts from all over Switzerland and beyond. The festival ends on Sunday, April 22.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.