The physical and emotional impact of colour

Paul Klee’s interest in colour was two-sided: empirical and emotional.

The former was based on his studies of various artists and scientists, including Goethe. Colour’s emotional impact came later, ostensibly during the artist’s turning point during his trip to Tunisia.

Writing in his diary during this voyage, he said: “Colour possesses me… colour and I are one. I am a painter.”

Colour was a major preoccupation by the time Klee was lecturing at the Bauhaus in Weimar in the early 1920s.

“Colours do not sing in unison… but in a kind of three-part harmony,” and “how enormous are the differences between red and a colour which contains no red at all!” are statements taken from his lectures.

With musician parents, a pianist wife and he himself a talented violinist, it is not surprising that Klee used terms like polyphony, colour harmonies and musical scoring in his theoretical writings and in his lectures at Weimar.

Discovery of colour

At the beginning of his career, Klee did not paint much and his use of colour was rather restrained.

His watercolours show that he was more interested in the value of a tone on the chromatic scale than in the psychological resonance of colour.

“Until the moment when he reported his ‘discovery’ of colour, Paul Klee concentrated on tonality, especially the scale of red, browns and rather dull greens,” explains art historian Michael Baumgartner.

But from 1913-14, his palette began to come alive.

“The primary colours – red, yellow and blue – assumed new importance, as did contrasts of complementary colours, from one end of the scale to the other,” says Baumgartner.

Intense light

A major influence on Klee, where colour was concerned, was the French artist Robert Delaunay, for whom Klee translated an article in 1913, entitled “La Lumière” (or “Light”).

The following year, Klee made a journey to Tunisia, where he discovered the emotive intensity of colour. His direct experience of the sensuality of the southern light was decisive on his work.

Until that time, Paul Klee had produced many drawings and graphic works but had painted relatively little, and then mainly in watercolour.

After the trip to Tunisia, it was as if Delaunay’s ideas, on which Klee had meditated a great deal, had fermented within him, giving birth to his own pictorial language.

Rainbows

Delaunay had also given Klee the idea of working directly on the colour spectrum.

As Klee wrote, the rainbow… “standing above every coloured thing, is the abstraction of every application, elaboration and combination of colours”.

It is interesting to note how Klee’s discovery of colour was followed by greater mastery of the technique of oil painting.

His compositions became more abstract, while exhibiting greater freedom of movement and gesture. The titles often refer to personal situations and experiences.

Values such as the dynamism of movement and the relationship between individual and cosmic energy began to emerge.

A few years later, taking these ideas as his foundation, Klee formulated his concept of Romanticism as a form of expressive freedom antithetical to Classicism.

Artist and scientist

Where research into colour is concerned, Klee made a dual contribution to modern art: as artist and as scientist.

Klee worked on colour with intuition and emotion and also with a methodological apparatus, which served to advance theoretical research in this domain.

“He interpreted Robert Delaunay’s theory of light and colour in a very personal way, turning it into his own pictorial poetic. But at the same time he conducted methodical experiments to broaden the scale of colour interaction, exploring complementary contrasts, or contrasts between warm and cold colours,” explains Baumgartner.

swissinfo, Raffaella Rossello

1911-14, Paul Klee begins to make his mark on the European art scene.

1911, he makes contact with the artists of the Blaue Reiter group.

1912, he meets Robert Delaunay in Paris. The influence of Delaunay’s experiments in the use of colour, shifts Klee’s focus from the psychological values of shapes to problems of light and colour.

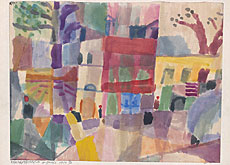

During a journey to Tunisia in 1914, with artists August Macke and Louis Moilliet, Klee was captivated by the colourful magic of the north African landscape.

He began to paint luminous watercolours, rendering geometrical elements in bright tones.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.