Detained Swiss in Libya hampered by legal fog

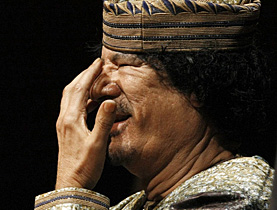

The upcoming trial of two Swiss men held in Libya for more than 75 weeks will offer clues as to whether Tripoli is exacting revenge or just upholding its laws.

Max Göldi and Rachid Hamdani are scheduled in early January to be tried for a second time in Libyan court, this time over business and tax violations. One thing is already evident: the Libyans have ignored their own laws handling the case.

“The rules for a fair trial are very clear,” said Daniel Graf, a spokesman for Amnesty International’s Zurich office. “Libya says this case is not about politics but so far there are more signs of it being a political trial than a fair trial. The next few days will offer hints as to which way this will go.”

Göldi and Hamdani were arrested in July 2008 just days after Geneva police briefly detained Hannibal Gaddafi, a son of leader Moammar Gaddafi, and his wife on charges they abused their domestic staff while at a luxury hotel in the city. The charges were later dropped and the Swiss apologised, hoping Göldi and Hamdani would be set free.

Instead the men were found guilty in absentia of violating Libya visa laws and were sentenced to 16 months in jail. The trial was speedy and closed to the public. The men’s lawyers were given little time to prepare and still do not know exactly which laws the Swiss allegedly broke.

The businessmen have been confined to the Swiss embassy in Tripoli and plan to appeal against the ruling. The appeal date has been pushed back until later in 2010.

Good news

Diana Eltahawy, human rights researcher on North Africa with Amnesty International’s headquarters in London, told swissinfo.ch the delay is good news for the Swiss. The extra time should help the men’s lawyers prepare a defence while also giving Bern and Tripoli some room to work out a settlement.

But fault for the lawyers not being prepared in the first place lies with Tripoli, Eltahawy said. While the Libyans have a right to charge the men, they have never produced written documents outlining the exact accusations. The defence lawyers have also been denied access to many documents.

“The Libyan code of criminal procedures carries some safeguards in accordance to international standards for defendants,” Eltahawy said. “But from what we’ve seen those safeguards are not always implemented.”

Under Libyan law, the men have the right to know immediately what they are being charged with, to speak with a lawyer freely and to have their case heard in an independent court. Those conditions were not met satisfactorily, she said.

“When this next trial over business and tax violations begins it will be a very intense time for the men and their families,” Graf said. “If the trial is unfair and results in an unacceptable sentence, we might move toward escalation.”

The Libyans meanwhile blame the Swiss for escalating the affair and have issued a 27-point list to make their case. It includes the Swiss leaking a photo of Hannibal Gaddafi taken during his arrest to the press and talking about a military operation to free the men by force.

Libyan system

So what exactly are Göldi and Hamdani up against? Eltahawy says it is difficult to draw comparisons between legal systems, but Libya, as with any country, has a judicial branch with its good and bad points.

The country considers itself a direct democracy like Switzerland. It is also a state signatory of international covenants on civil and political rights.

Libya is one of the few countries in the region that did not modify its laws to extend how long a person suspected of acts of terrorism can be held incommunicado. It is during that time a detainee suffers the greatest risk of being tortured.

But there are harsh penalties – even death – for speaking out against the government or for organising political protests. People accused of threatening national interests have hearings before a special state security court that observers say is basically a parallel legal system with few safeguards to protect human rights.

“Others have faced immigration charges but they were mostly from sub-Saharan Africa,” Eltahawy said. “This is a very particular case with the Swiss businessmen and it can’t be disassociated from the difficulties between the Libyan and Swiss governments.”

Libyan law says the men do not have to be present at the trial over business and tax issues, now scheduled for early January. But they do need to be present to appeal against the visa charges that brought the 16-month sentence. Otherwise the punishment will stick.

“Of course the problem is whether they risk going out of the embassy and being taken away,” Graf said. “It’s a very difficult decision. Even if the first trial had been fair, the sentence was not.”

Tim Neville, swissinfo.ch

July 15, 2008: Hannibal Gaddafi and his wife Aline are arrested at a Geneva hotel after reports that they have mistreated two servants. After two nights in detention, the couple are charged with inflicting physical injuries against the servants. The Gaddafis are released on bail and leave Switzerland.

July: Two Swiss nationals are arrested in Libya. Swiss businesses are forced to close their offices and the number of Swiss flights to Tripoli is cut. Bern sends a delegation to Libya.

January 2009: Talks are held in Davos with Seif al-Islam Gaddafi, one of the Libyan ruler’s sons. A diplomatic delegation travels to Tripoli.

April: Hannibal and his wife, along with the Libyan state, file a civil lawsuit against the Geneva authorities in a Geneva court.

May: Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Libya, reporting “significant progress”.

June: Libya withdraws most of its assets from Swiss bank accounts.

August: Merz, who meets the Libyan prime minister but not Gaddafi, apologises in Tripoli for the arrest. Swiss appoint arbitrator for international tribunal.

September: Libya does not let the two Swiss nationals leave the country, breaking a promise made to Merz that they would be free to return to Switzerland before September 1. Libya names its representative for the tribunal. Gaddafi and Merz meet on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York. The two nationals disappear after undergoing a medical check-up in Tripoli.

October: A Swiss delegation returns empty-handed from Tripoli. A 60-day limit for normalising relations between Switzerland and Libya passes with no sign of the two Swiss hostages held by Tripoli. The Swiss cabinet expresses irritation over Libya’s “systematic refusal” to implement agreements between the two countries.

November: Swiss ministers suspend treaty seeking to normalise relations with Tripoli and say they will pursue visa restrictions for Libyans.

December: Two businessmen allegedly sentenced to 16 months in prison and fined SFr1,600. Libya postpones the appeal and blames Switzerland for escalating the affair.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.