What the US pullback means for Switzerland’s climate priorities

The absence of the United States - the world’s largest economy and its second-largest polluter - casts a long shadow over international climate negotiations. For Switzerland, the US void has reinforced its position on climate finance, while hindering the possibility of a fossil fuel phase-out.

In January, the US notified the United Nations that it would pull out of the landmark Paris Agreement on climate change, reached ten years ago at its annual climate conference (COP). Two months before the withdrawal comes into effect, the US delegation chose not to attend the COP30, held earlier this month in the Amazon rainforest city of Belém, Brazil.

According to Switzerland’s chief climate negotiator Felix Wertli, the US used to always have a strong delegation whose negotiation positions often aligned with European countries. So, the “dynamic [in Brazil] was a bit different,” he noted, adding that it had felt taboo to mention the US absence, despite its outsized role in both climate change impact and finance.

Washington’s no-show was particularly felt in the final discussions over how to fund vulnerable countries’ climate adaptation needs, said Wertli. The “Baku to Belém Roadmap” plan to scale up climate finance to the tune of $1.3 trillion (CHF1 trillion) by 2035 remains, and, in Brazil, countries agreed to triple adaptation funding to roughly $120 billion per year. But the US exit means there is less available for financing.

“We now have one less donor country,” Wertli noted. He added that Switzerland “would have liked to have more discussion” with other parties on the issue before the adopted text’s wording was achieved by consensus.

Switzerland draws the line on climate financing

At the COP30 summit, Swiss Environment Minister Albert Rösti explained that increasing climate finance obligations would be a red line for Switzerland. But the UK and the European Union appeared more flexible in last-minute talks, saying they could possibly bend their position on finance if other countries, particularly oil producers, were more ambitious on limiting fossil fuels.

Switzerland’s firm refusal not to increase financing was also shaped by geopolitical realities and concerns over shrinking aid budgets from other donors, which had begun to cut assistance even before the change of administration in Washington. Several European states, including Switzerland, have redirected relief and development funding toward defence, while China has signalled it has no intention of filling Washington’s gap.

In the decade leading up to 2023, Switzerland’s climate finance had more than doubledExternal link – representing more than its fair shareExternal link, according to a 2024 report. And unlike many other donors who focused on providing loans, Swiss funding consisted mostly of grants, according to findingsExternal link by International relief organisations Oxfam and CARE.

In Belém, the issue of how to tackle climate adaptation was a pressing one, as funding goals agreed at the 2021 COP summit in Glasgow are set to expire this year.

As disasters intensify, developing countries on the climate frontlines face ever-rising costs caused by flooding, drought or higher sea levels, for example, further widening the adaptation funding gap. Yet with 60%External link of adaptation funding still involving loans rather than grants, countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands and Monaco that provide mostly grant-based funding, may find themselves particularly under pressure by the drop in climate funding.

For his part, Mohamed Adow, the founder and director of the Power Shift Africa, a Nairobi-based think tank, argued that European countries including Switzerland had watered down the new funding goals “to the lowest common denominator”, by seeking to triple finance without mentioning a baseline.

“They undermined the talks and scraped away protections poor countries were seeking in Belém,” Adow declared. This reflected other views that, despite the its absence, the revised US stance on international funding had influenced other wealthier countries to avoid strong financial commitments. In 2024, in its final year in government, the Biden administration had announced a commitment to scale up international climate finance.

“When high-income countries like Switzerland don’t come to climate conferences ready to increase support for frontline communities in low-income countries, it effectively dilutes the ambition of negotiations across the board,” said Richard Pearshouse, director of environment and human rights at Human Rights Watch.

More

COP30 analysis: too little, but still worthwhile

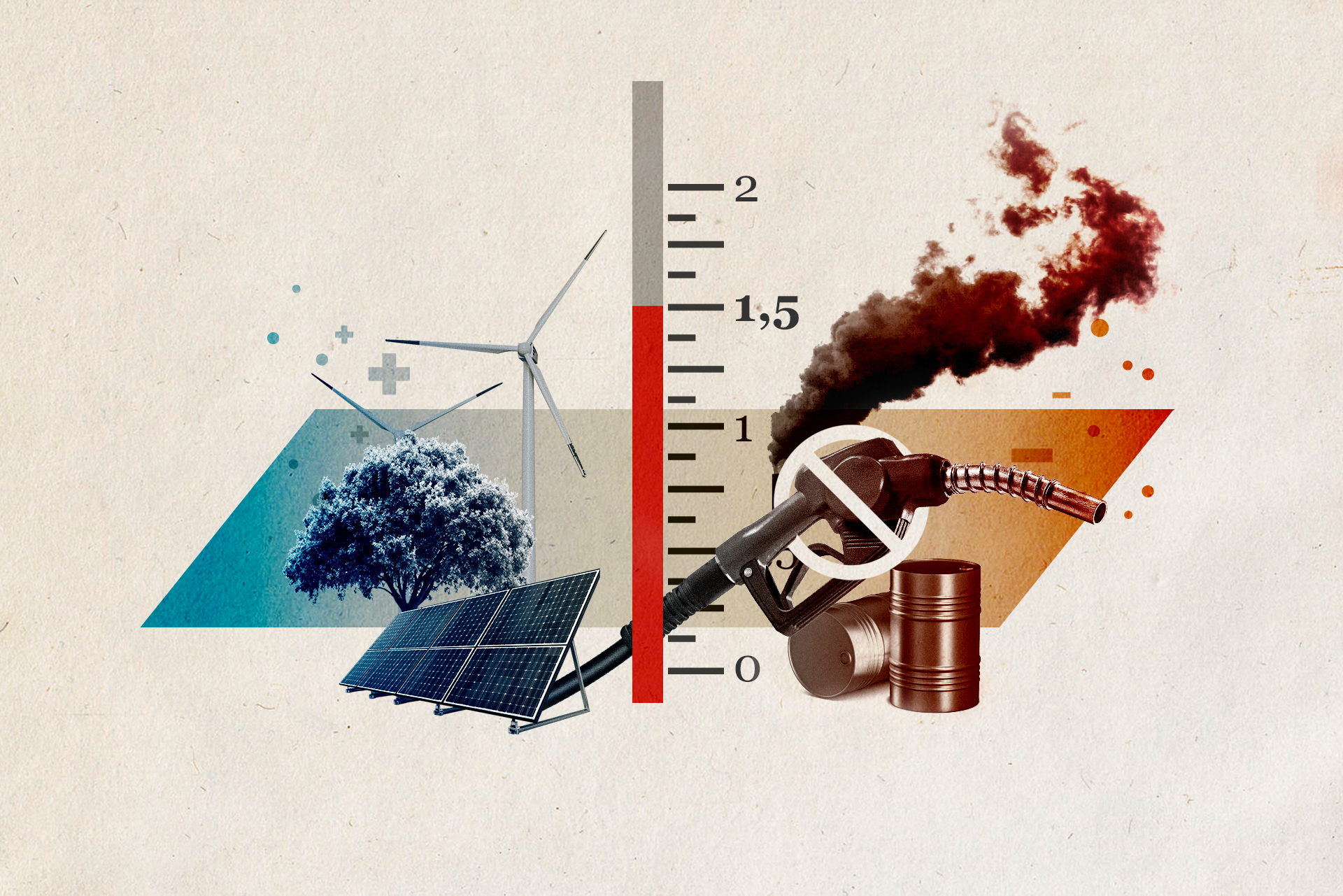

Status quo on fossil fuels

While the Trump administration has reversed policies supporting a transition to green energy sources and the EU has been under mounting pressure from automakers to dismiss its combustion engine ban, Switzerland joined other countries at COP30 in calling for a phase-out of fossil fuels.

But before leaving Belém, Rösti made it clear that the current geopolitical context complicated matters.

The Swiss environment minister said: “When the [US doesn’t reduce its CO2 emissions], and the US as a big country that can persuade China [to decarbonise] is absent, it makes it very difficult.”

At COP30, oil producers Saudi Arabia and Russia, as well as China, were ultimately responsible for blocking the call for a fossil fuel phase-out. Switzerland was also criticised for not doing enough to reduce its global carbon footprint at home, instead relying heavily on offsetting its emissions in developing countries.

Read more: COP30: Switzerland reinvigorates its climate offsetting plan

Before leaving Belém, Wertli insisted that much more should be done within the UN climate process to accelerate action.

“Key elements are still missing. As the body made to manage emissions, we still lack a space to discuss NDCs (nationally determined contributions or carbon emission targets) ten years after the Paris Agreement,” he noted.

He also expressed frustration with the lack of decisions to stop fossil fuels and deforestation. “We need to better understand how to manage these transitions in a manner that is just and informed by science,” he said.

International cooperation still alive

Despite US efforts to undermine multilateralism, Wertli insists that the Belém summit showed that international negotiations remain very much alive and that the “COP of truth”, as it was dubbed, reflected the realities of a complex negotiation process.

“It’s a success that we are here together, and have shown what we have achieved through the Paris Agreement, in spite of huge challenges,” the Swiss negotiator said. “There was one [country] missing, but 194 countries are committed to the process and want to be part of it.”

What is your opinion? Join the debate:

More

We can still solve the climate crisis – here’s how

Edited by Veronica DeVore/sb

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.