Scientist urges no let-up in fight against BSE

Ten years on from the BSE crisis, research has revealed the causes of the disease and made it possible to bring the epidemic under control.

But in an interview with swissinfo, Professor Adriano Aguzzi, a leading expert on degenerative brain diseases, warns that there are still many unanswered questions.

Ten years ago, bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE), commonly known as mad-cow disease, caused panic among European public health and veterinary authorities.

Millions of cows were slaughtered to stop the spread of the disease, which attacks the brain and nervous system with fatal results.

The epidemic has died down in recent years, and only four cases of BSE have been identified in Switzerland in 2004.

But new fears have emerged with the appearance in humans of new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), resulting from the consumption of infected beef.

Aguzzi, director of the Institute of Neuropathology at Zurich University, has made an outstanding contribution to the understanding of prions, the infectious particles which transmit diseases such as BSE.

swissinfo: In the past year or two, there has been less talk of mad-cow disease and the risk of it being transmitted to humans. Is this the fault of the media, or has the danger gone away?

Adriano Aguzzi: In public health, as in other fields, the media often focus almost exclusively – some would say hysterically – on a particular topic, which is then forgotten or superseded by something else.

The problem of BSE has all but disappeared from the media, but not unfortunately from the world around us. Nevertheless, there are good reasons for optimism, which was not the case a few years ago.

This is partly because the measures adopted over the past decade, beginning with the ban on animal proteins in livestock feed, have greatly reduced the spread of the disease among bovines, and therefore the danger of it being transmitted to humans.

swissinfo: A few years ago, there were still doubts as to whether BSE was really caused by animal proteins in livestock feed. Is this now proven beyond all doubt?

A.A.: Yes, there is no longer any doubt that BSE is transmitted by animal proteins in livestock feed. However, there are still some incorrigible individuals, including some scientists, who propound other theories, citing bacteria or neurotoxic substances. Some parties in this affair are clearly trying to evade their responsibilities.

Personally, I am prepared to stake my whole reputation on the fact that mad-cow disease is caused by animal proteins in feedstuffs.

swissinfo: Where did the idea originate of feeding cattle with concentrates containing residues from other bovines? Was the quest for profit solely to blame?

A.A.: Certainly it was an unnatural practice, making cannibals of herbivorous animals. But it was not motivated solely by financial considerations: there were also what one might term ecological reasons.

Do not forget that in countries like Switzerland we simply discard many parts of a cow which in other regions of the world are quite regularly used for human consumption.

Twenty years ago, it seemed absurd to incinerate these excellent proteins, which have a high energy value. Instead of destroying them, it was considered better to recycle them by transforming them into livestock feed.

swissinfo: Many people who have since contracted new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease are paying the price for this mistake. However, this disease seems to have spread less aggressively than was feared in the late 1990s?

A.A.: That is true. Until a few years ago, I was terrified by the idea that there might be a widespread epidemic, with hundreds of thousands of people losing their lives. Fortunately, this epidemic has not occurred and, with every passing year, the risk diminishes.

It is true that new variant CJD has so far claimed 160 victims. This is a terrible tragedy for each of them and their families, and it could have been avoided. But the scale of the tragedy has been more limited than with many other diseases.

swissinfo: Nevertheless, it would seem that there are still many questions remaining regarding the incubation period – the time between the prions being transmitted and the onset of the disease?

A.A.: We need to be cautious, given that the incubation period can be as long as 20, 30 or even 40 years. We know how many people have died, but we do not know how many are infected or how many are apparently healthy carriers of the disease.

Fortunately, this is a disease that cannot be transmitted by sexual contact, as in the case of Aids. There are, however, still serious concerns that it could be transmitted by blood transfusions from undiagnosed carriers. Pathogenic prions have been found in blood donated by people who were not ill at the time they gave blood.

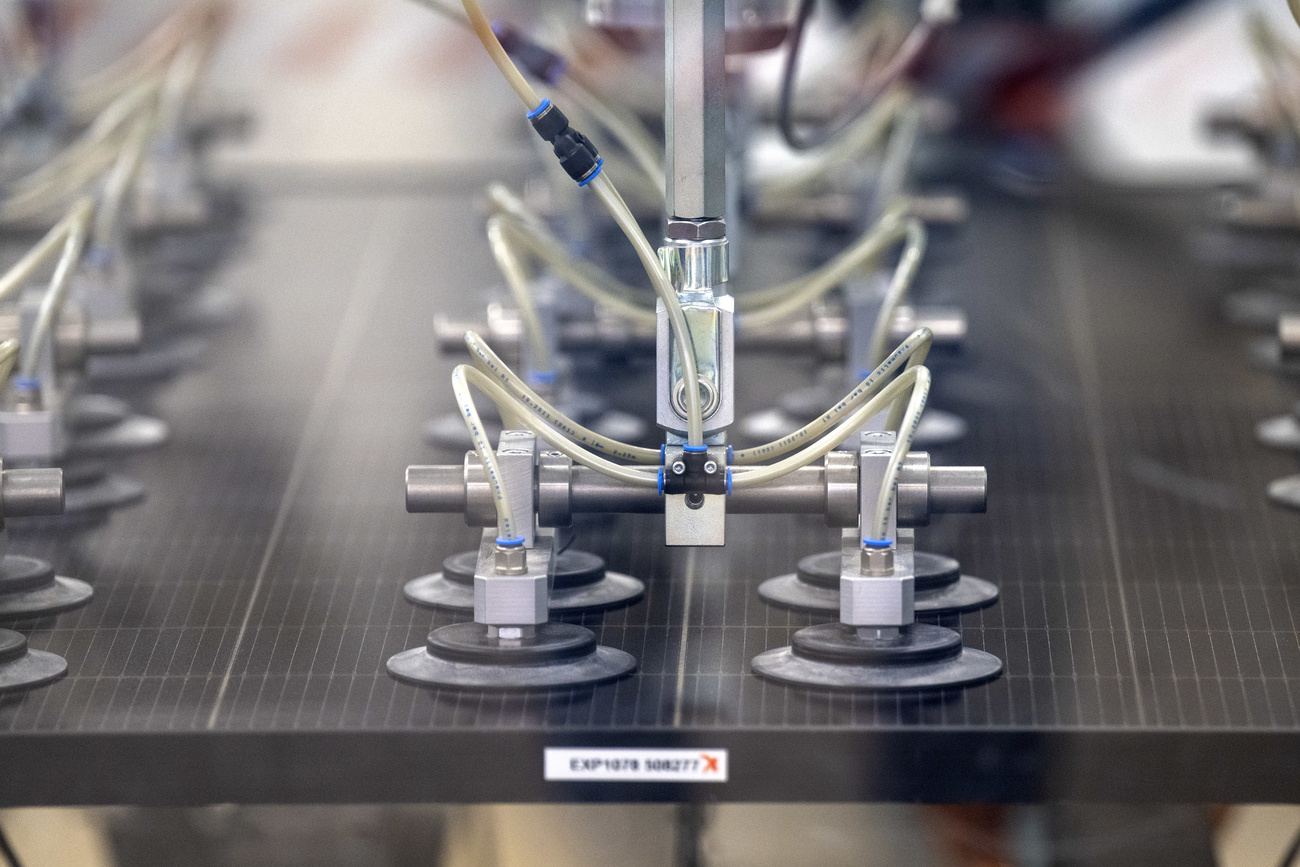

For this reason, our institute is analysing thousands of samples of lymphatic tissue – such as tonsils or spleens – to try and identify prions, and assess the incidence of infection in the general population.

swissinfo: If infection rates were found to be high, is there a way of preventing the disease from spreading by blocking the action of the prions on the brain?

A.A.: There are still many unanswered questions, which we are working on in our research. For example, what is the role of prions, what molecules are involved in their reproduction, and by what mechanisms do pathogenic prions damage the brain?

On the other hand, we do now understand how prions move from the digestive tract to the brain. We have also developed a small arsenal of drugs that enable us to block this transfer.

The real problem, though, is knowing who is infected and when the infection occurred. Therefore, we are trying to develop diagnostic tools which would enable us to rapidly detect the transmission of pathogenic prions to human beings.

swissinfo-interview: Armando Mombelli

Adriano Aguzzi has studied medicine and biology in Germany, Switzerland, the United States and Austria.

The Italian-born researcher has worked at Zurich University since 1993.

He became director of the university’s Institute of Neuropathology in 2004.

He has received many major international awards, including the Robert Koch Prize in 2003 and the Marcel Benoist Prize in 2004.

Bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE) is caused by feedstuffs containing recycled animal proteins.

Since 1990, around 200,000 cases of BSE have been recorded worldwide, of which 190,000 were in Britain alone.

Switzerland, which has recorded more than 450 cases, has adopted a large number of measures over the past ten years to halt the spread of the epidemic.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.