From an igloo to worldwide renown

In 1936 a small group of scientists gathered in an igloo in Davos to conduct their very first snow experiments. The aim: to find out more about deadly avalanches.

From these humble beginnings grew the

Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF), which is now famed for its expertise and produces the all-important avalanche bulletins for skiers during the wintertime.

Davos, the mountain resort in eastern Switzerland, may be known to many as the home of the World Economic Forum or even as the setting for Thomas Mann’s sanatorium novel The Magic Mountain.

But it is also where the SLF is based and, on a crisp, sunny March morning it is easy to see why. The snow-capped mountains that surround it are, as the SLF’s website states, part of its natural laboratory.

The institute is only one of three of its kind in the world– the others being in India and France – and is by far the oldest.

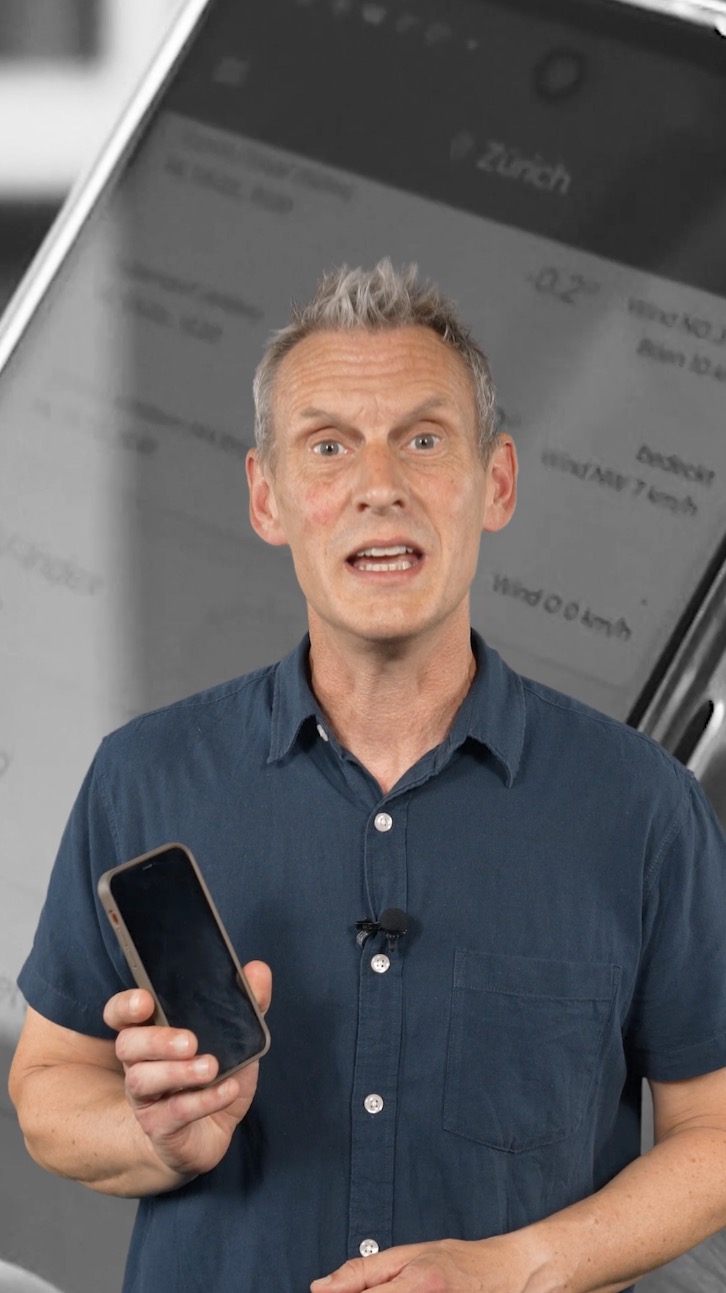

“Many factors came together as to why it was set up,” Jürg Schweizer, head of the SLF research unit on warning and prevention, said at a media event in Davos to mark the anniversary.

“There was a particularly severe winter in 1930/1, tourism picked up after the depression, hydropower stations were built in the late 1920s, and foresters were concerned about how to prevent avalanches,” he told swissinfo.ch.

The Swiss Federal Commission for Snow and Avalanche Research was founded in Bern in 1931 but it soon became clear that field work was necessary. Mountainous Davos was chosen, with the first experiments conducted in an igloo in the village.

Snow pioneers

“Of course that igloo melted away in early 1936 so they decided to move up to the 2,662-metre altitude Weissfluhjoch mountain above Davos, building a wooden shed there,” said Schweizer.

In 1942 the scientists gained a proper building. This was to remain the SLF’s headquarters until the present site down in the village opened in 1996.

Early research focused on development of the snowpack, snow mechanics and avalanche formation, as well as snow structure.

“It was a new area of research as the field didn’t really exist before, so most people were either engineers coming from geotechnics or mineralogists. There was also a geologist and a meteorologist,” said Schweizer.

“It was obviously a very fruitful collaboration, they brought their own tools, and adapted them for the snow and within a couple of years they made incredible progress in what they knew about snow.”

Avalanche bulletin

In 1945 the SLF took over the avalanche bulletin from the army, which had established a warning service during the Second World War to protect troops stationed in the mountains.

By 1950 there were around 20 observation stations providing data for a weekly bulletin. It was, by today’s standards, quite basic. There weren’t any danger levels included – this only came much later when the European system was harmonised. Nowadays the bulletin is produced twice a day.

The terrible avalanche winter of 1951, however, resulted in 98 fatalities. This prompted a fundamental change – the avalanche warning network and avalanche defence structures were boosted, with SLF involvement.

These defence measures have seen a huge reduction in the number of deaths in villages and on the roads. There are now currently around 25 avalanche fatalities a year in the Swiss Alps, mainly involving off-piste skiers.

Today’s SLF is an internationally-connected institute with 130 employees and a budget of SFr15 million ($16.6 million). It is now part of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology through its affiliation to the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL).

“I would say in the domains in which we are active we are certainly world leaders or among the two to three leaders,” SLF head Jakob Rhyner told swissinfo.ch.

Icecream, anyone?

SLF also collaborates with industry, such as helping ski stations with artificial snow production when snow is scarce.

And, as the media could see through an impressive demonstration, the institute is also working with Nestlé to produce ice cream in its snow laboratory. As was pointed out: snow is ice and air and ice cream is the same, only with sugar solution added.

Climate change is also a topic. Should the snow disappear there would be no avalanches, but this is not likely to happen for more than 50 years, said Rhyner. Meanwhile the nature of avalanches will change.

“We will certainly have more wet snow avalanches, such as slush flows which are a mixture of water and snow. Natural hazards based on melted snow, such as torrents, are also becoming more important, which we at least partially try to treat with similar methods to avalanches.”

So snow and avalanches remain the SLF’s core business, just as they were in the igloo 75 years ago.

“The demands on avalanche forecasting and warning and for a better understanding of how far avalanches go are steadily increasing because mobility demands are increasing and people want to have information over a longer period of time,” Rhyner said.

“So even after 75 years and a lot of research, there is still a need to go further ahead in our scientific understanding.”

1936: beginnings as igloo in Davos Platz area of the village and then as a wood hut on Weissfluhjoch mountain, 6 employees (engineers and natural scientists), budget winter 1935/36: cSFr11,000 (around SFr88,000 today).

2011: headquarters in Davos Dorf area of the village with workshops, avalanche warning centre, training and exhibition centre, 130 employees (engineers, natural scientists, technicians and administrative staff), budget: c.SFr15 million of which 50% comes from the government.

Anniversary year: SLF is celebrating with its mother house Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL (which celebrated 125 year anniversary in 2010) through a series of events. The kick-off was March 18, a public open day was held on March 20.

A study published on March 21 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, which included Canadian, Italian and Swiss researchers – including those from the WSL and SLF – has shown that Canadian avalanche victims die more quickly than Swiss ones.

This was because of the heavier coastal snow, more traumatic injuries and the limited medical expertise of rescuers, according to the study. But Canadian victims were rescued faster than the Swiss ones, usually by their skiing companions.

The chances of surviving an avalanche were therefore estimated to be about the same in the two countries, at around 46 per cent.

The study looked at around 1,250 avalanche accidents between 1980 and 2005 in which victims were totally buried by the snow.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.