Silk road holds out promise of a better future

India is the second largest silk producer in the world, and hundreds of thousands of underprivileged people depend on the industry for survival.

The growing of mulberry plants, the rearing of silkworms and the reeling of yarn generate jobs and income for minorities and the landless, for marginal farmers and the lower castes. In a programme called Seri2000, the Swiss Development Agency is promoting sericulture to help alleviate poverty.

The southern state of Karnataka is responsible for more than 60 per cent of India’s annual production of 14,000 tons of raw silk. In a typical village like Badanaguppe, where silkworm rearing is a way of life, the inhabitants buy eggs from state or private firms.

Mariyamma, aged 18, said sericulture was the most reliable source of income. “Even without land, people can live from silkworm-rearing. In this community, there are quite a few who just buy mulberry leaf, hire the equipment they need and start rearing. And with family labour, you can maximise the benefit.”

With four to five crops in a year, Mariyamma’s family produces about 100 kilogrammes of cocoons annually. Of relatively low quality, they fetch about 70-75 rupees a kilo at market. After expenses, their annual income is about 4,500 rupees (SFr150).

Threat of disease

A fungal disease is threatening the latest batch of silkworms and it looks like they might lose the lot. “It’s a real disaster if the total crop goes because we are totally dependent on this business,” she said. “Also, we buy mulberry leaves so we have to pay back the leaf sellers.”

Ideally, villagers would have a separate breeding house where humidity, temperature, ventilation and hygienic conditions could be better maintained. However, most people don’t have the money for such a venture and they set aside a space in their home for the rearing trays and wooden racks.

“In the rearing house, space is a constraint,” said Shankarappa, another villager, who cultivates two acres of mulberry. “Everything’s cramped into one building and that causes problems of hygiene.

“The Uzi fly is another problem. Even though we use tray covers, we still lose larvae to Uzi so a separate rearing house would be better.”

Shortage of water

In Karnataka state, where 30 per cent of the sericulture is rain-fed rather than irrigated, harvesting the available water is a priority.

“We’re totally dependent on rainfall,” said Shankarappa, who cultivates two acres of mulberry. “And soil fertility should be improved by applying organic manures.”

Seri2000 supports the breeding of better silkworms, cultivation of better varieties of mulberry, and the development of new technologies and cost-effective irrigation systems.

The local breeds of silkworm reproduce several times a year but their cocoons contain less silk and are of lower quality. Improved breeds produce bigger white cocoons but their eggs are more expensive and the maintenance more complex.

Cross-breeding is a solution, said Seri2000’s programme director, H R Girija. “What we have chosen to do is to support those breeds which do not necessarily give you fantastically high levels of yield but more consistent yields and which are more disease-resistant in average rearing conditions.”

“Our focus group – small and marginal farmers – can have access to better performing breeds without necessarily having to increase their input and this can in itself contribute to a higher income”

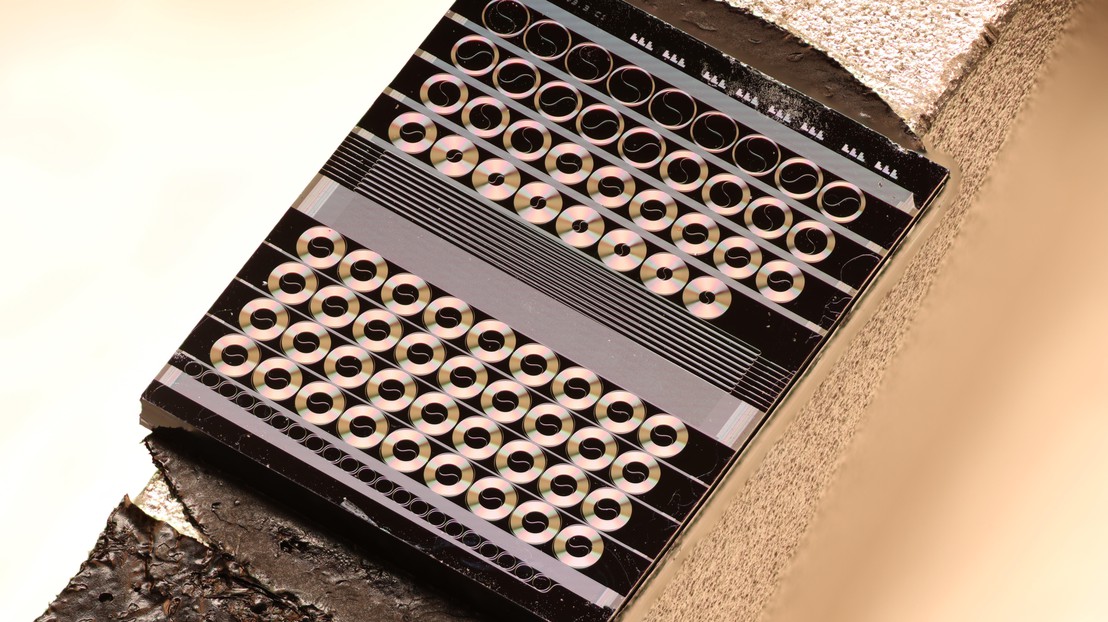

After about 25 days, the worms are placed on huge bamboo frames known as chandrike where they begin to spin their cocoons. After three days the cocoon is ready and after a further two or three days the worm becomes a pupa. Then the harvest can begin.

Mountains of cocoons

Auction time is a fast and furious business at the biggest cocoon market in Asia in the town of Ramanagaram, 50 kilometres southwest of Bangalore.

In this huge, high-ceilinged hall, mountains of yellow cocoons lie on simple, metal frames. Buyers are examining them critically. Shape, firmness and weight as well as the proportion of soiled and damaged cocoons determine the price.

Every day of the year apart from two national holidays, 600 farmers and 600 reelers come here to buy and sell. Daily trade is 30 tons of cocoons or a turnover of about 3.5 to five million rupees.

The price hovers around 135 rupees per kilo. After the auction, the cocoons are weighed and paid for. In front of the hall, satisfied customers count their bundles of notes. With huge sacks balanced precariously on their heads and luggage racks, cyclists transport the cocoons to the reeling units.

Once the cocoons have arrived at the reeling units, they are boiled in water to kill the worms and loosen the substance which holds the filament together. Depending on the breed of silkworm and the quality of the cocoons, a cocoon contains between 350 and 1,200 metres of filament. A thread is made by twisting together the fibres from several cocoons.

Low profit margins

With profits completely dependant on the yield from the cocoons, margins are very low. When Dundaiah or his brother from the village of Mellalli go to the local cocoon market, they tend to buy the cheapest cocoons which in turn have the lowest yield.

“I need about 15 kilos of cocoons to produce a kilo of silk which we sell at the Bangalore Silk Exchange. We get about 1,200 rupees for a kilo of silk,” he said.

The reeling unit in Mellalli, like many in India, is very simple and is still turned by hand. Improving the fuel efficiency of the stoves in the reeling units has been another aim of the Swiss-funded programme. Dundaiah uses new stoves, which use less fuel and give out less smoke.

“Basically we didn’t really support the development of this technology,” explained Girija. “But we supported extensive field trials under different conditions over one year and then used the local network of the masons to build them.”

Dundaiah’s brother employs 18 people, who receive 40 rupees a day. Work in the reeling unit is not easy.

Some workers said the fumes and the smoke caused them to cough a lot and they have repeated skin infections from dipping their hands into the boiling water. However, they also pointed out that the industry and the wages it provides is their only means of livelihood.

by Vincent Landon

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.