Positive signs: Swiss deaf federation marks 75 years of adversity

Deaf people in Switzerland used to be pressured not to marry and not to have children in the interest of public health. In the 1970s they were still being beaten in school if they used sign language. The progress made over the past 75 years makes for fascinating but uneasy reading, and, as the Covid-19 crisis shows, many challenges remain.

“We were totally forgotten about. In the most dramatic phase of the pandemic deaf people had absolutely no access to life-saving information. There was great concern everywhere,” Dr Tatjana Binggeli, president of the Swiss Federation of the DeafExternal link, told SWI swissinfo.ch.

But before getting onto current issues, let’s go back to February 17, 1946, when eight deaf associations from German-speaking Switzerland, fed up with being treated like second-class citizens, joined forces to give deaf people a louder voice. Eight more joined the same year, including one from French-speaking Switzerland and one from Italian-speaking Ticino.

“Deaf people were massively discriminated against by society because of their deafness. What’s more, they didn’t have their own voice and were controlled by hearing people, who acted as their guardians,” Binggeli explained through an interpreter at the federation’s headquarters in Zurich.

The situation was grim for deaf people in Switzerland. They were assumed to be morally wanting – especially women, who, it was feared, could be sexually active and, god forbid, get pregnant. Deaf men were accused of being stubborn and irascible and frequently got into conflicts at work, according to a book published by the federationExternal link to mark its 75th anniversary.

There are no official statistics, but the Swiss Federation of the Deaf estimates there are 10,000 deaf people in Switzerland and a further 800,000 classified as hard of hearing in a population of 8.6 million.

Tatjana Binggeli says the fact that it’s not even clear how many deaf people live in Switzerland – because the Federal Statistical Office doesn’t count them – “is a further sign of the disregard or ignorance concerning […] a minority in Switzerland”.

Worldwide, an estimated 9% of deaf people are children. Around 90% of deaf children have hearing parents.

Most deaf children in Switzerland learnt sign language in deaf schools, signing with each other in the playground and in their free time. In the early days, since there was no standardised Swiss sign language, various school dialects appeared. As a result, sign language in Switzerland comprises not only the three national languages, but also regional dialects which can be traced back to the different school locations.

Here are some FAQs on deaf definitionsExternal link from the National Association of the Deaf in the US.

Even deaf pioneer Eugen Sutermeister, who founded the Swiss Welfare Association for the Deaf and Dumb (now called Sonos), didn’t exactly have a positive self-image. In his Six Rules for Interacting with Deaf-mute Adults, written for hearing people in 1900, he said a hearing person should “patiently bear a deaf person with all his weaknesses” and that “the character flaws of a deaf person lie in his affliction”.

Welfare organisations took a fundamentally paternalistic attitude towards deaf people. They offered help when looking for jobs and settled disputes at work and in their daily life, but they didn’t entrust them with much independence. Deaf people were sometimes put under a guardianship and needed their guardian’s permission to change jobs or get married.

“Deaf people were completely excluded from educational programmes,” Binggeli said. “This began in primary school, with no teaching in sign language, and continued through their life. We still face this problem today.”

More

Listening to deaf children’s needs

Binggeli is a notable exception. Born deaf, she attended various schools for the deaf before switching, aged 17, to a high school in Bern with hearing students. However, the school director didn’t believe a handicapped person – as the director saw deaf people – could study at a mainstream school. Binggeli was kicked out and moved to another high school. She passed her exams and went on to gain degrees in medicine and biomedicine, working in various hospitals. She later became the first deaf person in Switzerland to get a doctorate in scientific medicine, passing summa cum laude.

No signing

The first deaf schools in Switzerland appeared at the beginning of the 19th century as a result of private initiatives. The aim was to give deaf people a school education, a religious upbringing and vocational training.

Things took a turn for the worse in 1880. At a congress in Milan education experts and doctors from all over Europe – almost all of them hearing – discussed how to educate deaf people. They decided that sign language must be banned from classrooms and that deaf people must be taught to lip-read and speak (oralism). As a result, signing was forbidden in Swiss classrooms until at least the 1970s, with offenders often facing corporal punishment.

“Historically, this congress was immensely important. It had a dramatic influence on the education and lives of deaf people,” Binggeli said. “People were banned from using their mother tongue, and access to jobs, politics and society was made considerably harder. It obviously undermined a self-determined life – the decision was taken for us. The situation now is not as extreme as back then, but it still exists.”

The problem was that often so much time was spent learning how to speak and lip-read that there was little time left for the basic education. What’s more, despite the time spent on oralism, many students were still unable to follow the spoken classes and were therefore disadvantaged in the classroom and later in the job market.

US movement

Slowly, however, things began to change. In 1960 a Swiss delegate who had attended the third World Deaf Congress in Wiesbaden, Germany, concluded that deaf people in Switzerland relied too heavily on “hearing helpers”. The same year, a Swiss newsletter for deaf people noted that “in Germany or Italy a lot of the hard lobbying was done by deaf people themselves”.

While many deaf people in Switzerland were proud that they could express themselves without signing, in the 1970s sign language was increasingly being used at international congresses and some Swiss delegates couldn’t follow what was going on.

The epicentre of the deaf movement at the time was Gallaudet College (now University) in Washington, DC. Founded in 1864 – and recently the setting of a Netflix reality series, Deaf U – it is officially bilingual, with American Sign Language (ASL) and written English used for instruction and by the college community. It is the first, and only, institution in the world for the advanced education of the deaf and hard of hearing.

“A couple of deaf Swiss spent time at Gallaudet in the 1970s and 1980s and experienced the free use of sign language in a society where everything was possible for deaf people,” said Binggeli, who has also visited Gallaudet. “They were very, very impressed by what they saw, and when they returned to Switzerland, they worked hard to achieve the same here, including a greater acceptance of sign language.”

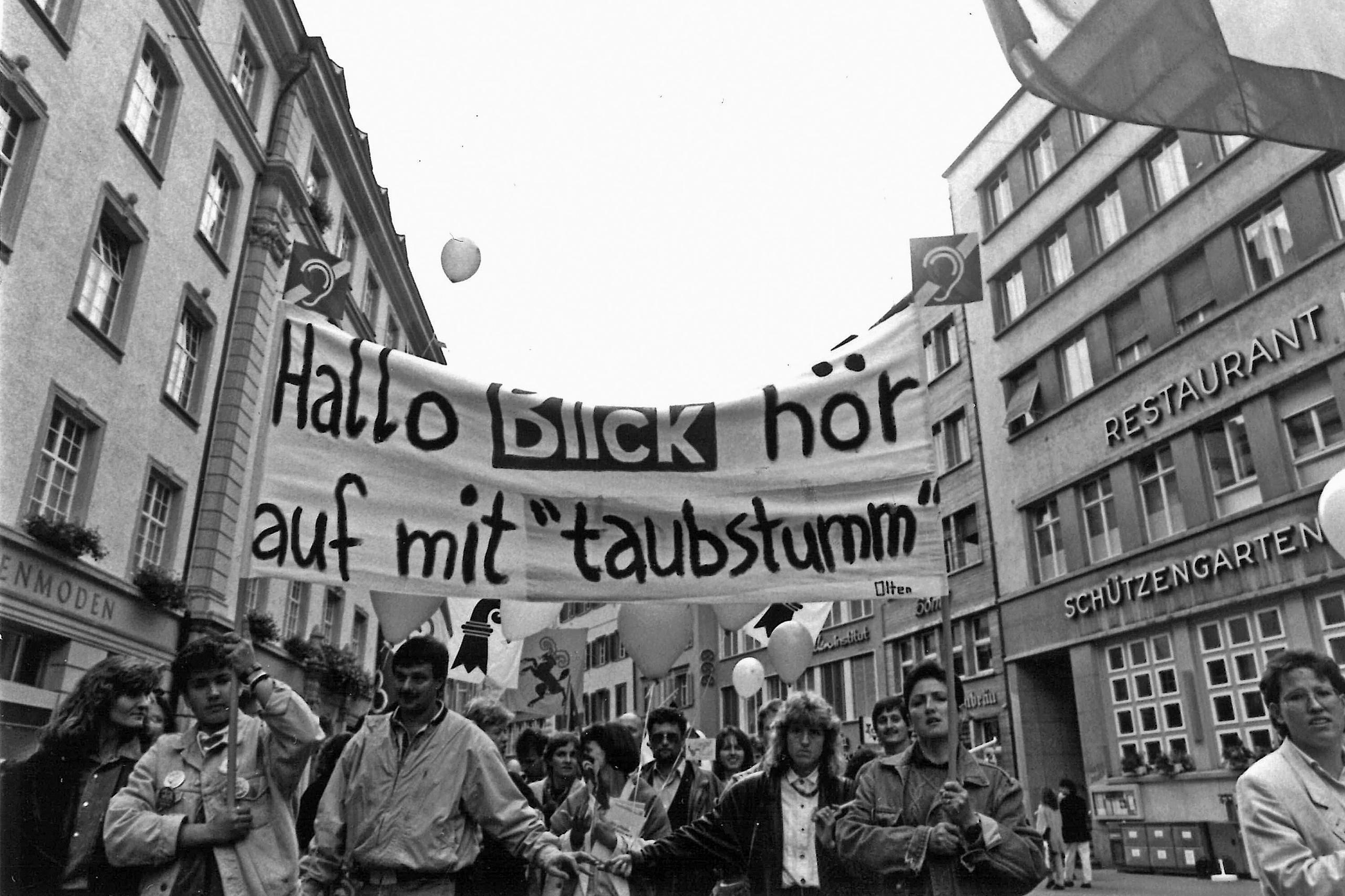

There were certainly plenty of hurdles, from a lack of money and political will to opposition from hearing parents who were worried that sign language would lead to social isolation for their deaf children. Some deaf people themselves were against signing in classrooms. But in the 1980s the Swiss public’s awareness of deaf people and the effectiveness of the representation of their interests increased significantly.

Achievements

Since then, the federation has notched up several significant achievements, including the development of educational programmes, seminars and courses by deaf people for deaf people. It has also become more professional and powerful, lobbying hard for the legal recognition of sign language and the interests of the country’s 10,000 deaf people and 800,000 people who are hard of hearing.

And what has the government done? “Unfortunately not very much,” according to Binggeli. The law on equality for people with disabilities entered into force in 2004 but parts of it are worded in quite a vague way, she says, and there’s always an “endless discussion” about who covers the costs: the municipalities, the cantons or the federal government.

“Switzerland is still a very socially conservative country – compared with other more progressive countries it doesn’t present a very good picture,” she said.

She says another thing that’s lacking in Switzerland is a neutral, independent information centre for parents of deaf children. “The most important thing is that the baby can communicate with its family. And to that end we recommend the whole family learn sign language. With sign language children have a language with which they can express themselves and interact with their family, while they learn spoken language at the same time. The Swiss Federation for the Deaf promotes a bilingual education.”

Direct democracy

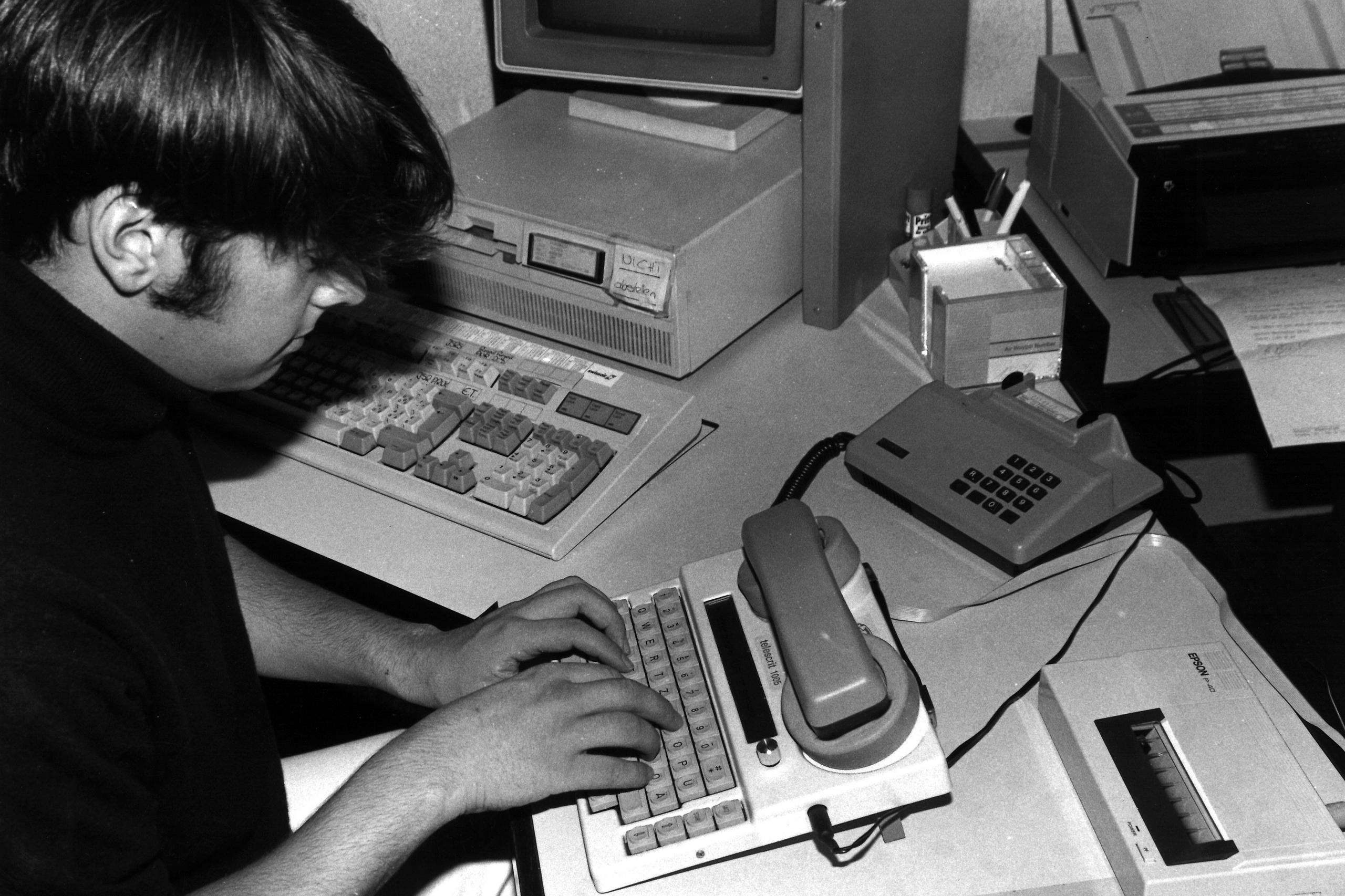

While the internet has been a gamechanger in many respects for deaf people, offering new communication possibilities, Binggeli explains that voice-recognition software is inaccessible for many deaf people and the internet is still text-based, which can also be a problem.

“One reason for this is that often with deaf people the educational level is very low for the reasons mentioned earlier [struggling in the classroom]. But this has got nothing at all to do with intelligence, rather with the barriers preventing information being accessible in sign language,” she said.

This is also a problem when it comes to the Swiss system of direct democracy, which involves the public going to the polls four times a year to vote on various issues. Each Swiss citizen receives a government booklet explaining the pros and cons of what’s at stake. But as Binggeli points out, “these texts are very complex and often not very easy to read – even for hearing people”.

“But hearing people have alternatives [to get information, such as television and radio] that we don’t have. And that’s why we need these texts in sign language. Just as they are read aloud to the blind, we need a visual form in sign language at the same level.”

She says that thanks to pressure from the federation, since 2018 the government has also published information on nationwide votesExternal link in the country’s three sign languages (German/DSGS, French/LSF and Italian/LIS). This video, for example, explains the challenge to the government’s Covid-19 policy (which voters rejected last month):

Emergency information

Most deaf people don’t consider themselves handicapped but members of a cultural and linguistic minority, with sign language as their mother tongue.

Today the federation’s main focus is on gaining legal recognition for sign language, which Binggeli said “mustn’t be a symbolic gesture but must contain concrete protection and promotion of the language – similar to that for Romansh”, a Swiss national language spoken by around 50,000 people.

Although measures like the Alertswiss appExternal link inform deaf people of nationwide sirens and other information broadcast via radio in the event of an emergency, the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the limits of this approach – not to mention the impossibility of lip-reading when masks are worn.

“The coronavirus pandemic is a really good example of how high the barriers are to important information. We were totally forgotten about,” Binggeli said. “We then contacted the government and demanded that sign language interpreters be made available for public information. And very quickly interpreters appeared at all government press conferences on the television.”

No deaf person has ever been elected to federal parliament in Switzerland, unlike in many other countries, for example Shirley Pinto in Israel last monthExternal link. Binggeli says she wanted to enter politics when she was 20, but she was barred from doing so.

“Political participation for deaf people remains impossible. Many, many barriers still exist. For example, we can’t follow the political debates in parliament. Political awareness is slowly growing, and there might now be interpreters at party meetings of delegates, but that remains the exception. They should be available to everyone as a matter of course. People shouldn’t have to ask ‘Is someone [deaf] coming? Do we need to provide an interpreter?’ An interpreter should just be there.”

So will we see a deaf Swiss government minister in our lifetime? “I’d really like to see that. To enter politics as a deaf person has always been my dream, but at the moment it’s just not feasible. But for this dream to become reality one day – that’s what I’m fighting for now and for the next generation.”

1946 – founding in Bern of the Swiss Federation of the Deaf

1957 – joins the World Federation of the Deaf

From 1981 – monthly broadcast of Sehen statt Hören on Swiss television, the first programme with sign language.

September 27, 1981 – Day of Deaf People. Events all across Switzerland and press coverage.

1982 – first Swiss conference for the deaf

1982 – programme Ecoutez-voir launched in French-speaking Switzerland

1982 – first sign languages courses for interpreters launched

1987 – federation publishes its magazine

1987 – some television subtitles are offered in Ticino

1993 – Motion for the recognition of sign language

1998 – Waiver of the military tax for deaf people

2004 – Law on equality for people with disabilitiesExternal link enters into force

2008 – Responsibility for train sign language interpreters handed to cantons

From 2008 – Tagesschau and Meteo available in sign language

2018 – Launch of app Alertswiss, which enables deaf people to register the national practice sirens. First one carried out on February 6, 2019.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!