Forgotten Swiss peace pact has lessons for Europe on ending bloodshed

Hailed in 1925 as a diplomatic triumph, the Locarno Pact – named after the Swiss city where it was negotiated – ushered in a brief period of peace after the First World War. What can today’s peacemakers learn as Europe once again deals with war, rising American isolationism, and shifting power among the great states?

Popular histories mark the end of the First World War with the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, when Germany was forced to accept responsibility for the bloodiest conflict then known.

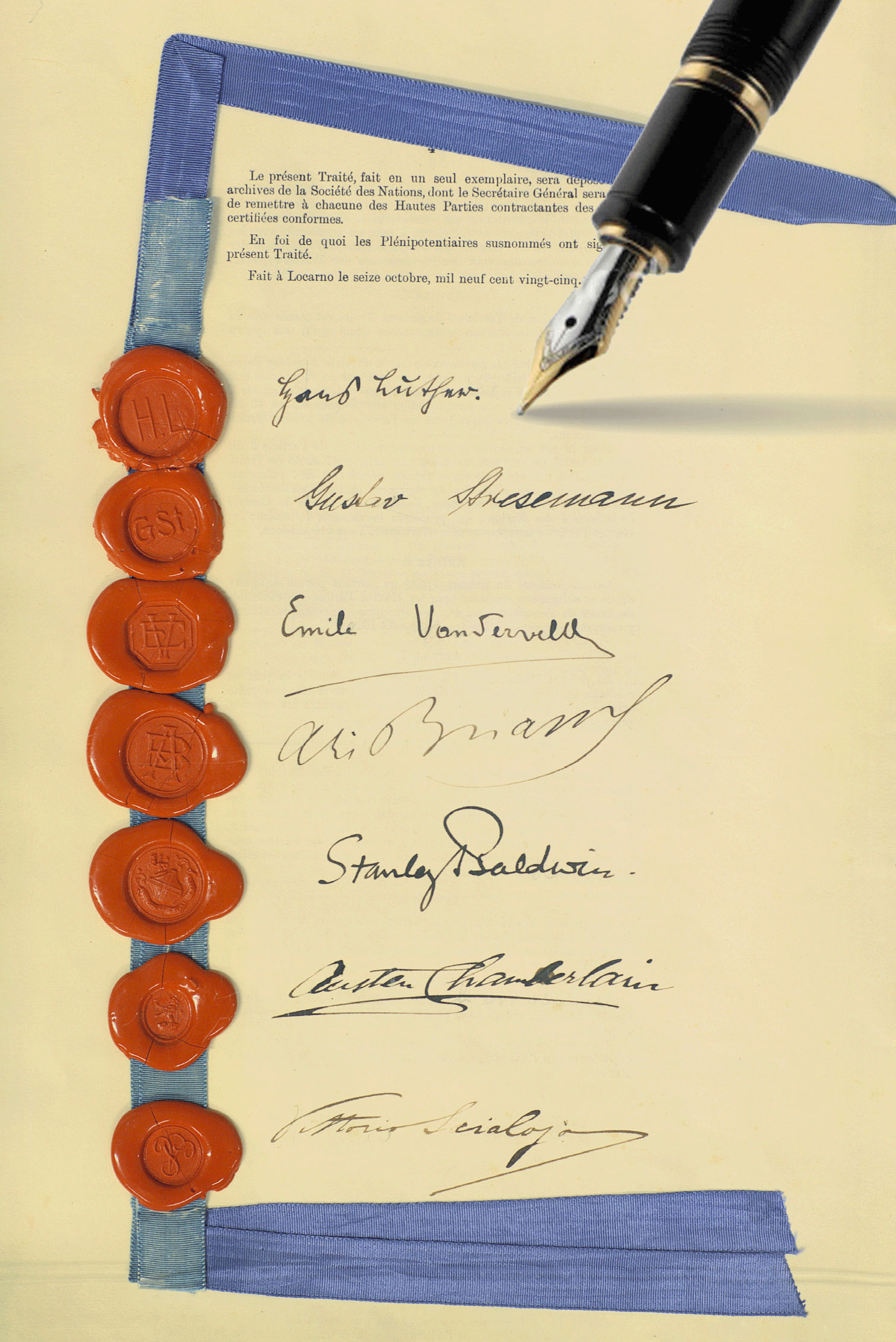

Yet many historians argue that a true settlementExternal link was only reached six years later in Switzerland. There, diplomats spent ten days hammering out treaties of the lesser-known Locarno Pact. The main signatories, Germany, France, Britain, Italy and Belgium, renouncedExternal link force in all cases but self-defence.

The Pact was celebrated as a diplomatic milestone, capping years of confrontation between the major European powers.

“It was the most fundamental agreement for the stabilisation of Europe after World War I,” said Sacha Zala, director of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland (Dodis) research centre.

The Pact confirmedExternal link Germany’s borders with France and Belgium and reaffirmed the demilitarised status of the Rhineland established at Versailles. It was significant enough to earn the main negotiators – the foreign ministers of FranceExternal link, Germany and BritainExternal link – the Nobel Peace Prize.

But reconciliation was short-lived. In 1936, Adolf Hitler, by then chancellor of Germany, broke the accord by sending troopsExternal link into the Rhineland. The Second World War erupted just three years later.

Now, on the centenary of the Pact and with Russia waging a war of attrition in Ukraine on Europe’s eastern flank, experts believe that Locarno offers lessons – both constructive and cautionary – for how to once again bring peace to the continent.

Securing Europe as the US turns away

One thing that Europe can relearn is to avoid relying on the United States for its security. After fighting alongside the British and French during the First World War, the Americans refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles or join the League of Nations, even though President Woodrow Wilson had been a leading architect of the precursor to the United Nations.

While the US pursued an isolationist policy and stayed away from Locarno, the European states negotiated amongst themselves. Under the Pact, Germany agreed to resolve any territorial disputes with France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Poland through independent arbitration, with mediation by a neutral third party. Locarno paved the way for Germany to join the League of Nations the following yearExternal link.

“The key powers were talking about peace for the peoples of Europe – there was a lot of reference to Europe as this kind of collective entity,” said Peter Jackson, a history professor at the University of Glasgow and an expert on the interwar period.

Discover how the city of Locarno has embraced the legacy of peace left by the Pact:

More

How Locarno became the ‘city of peace’

The echoes reverberate today. A US turn away from Europe, particularly under the presidency of Donald Trump, is again being felt. The president has created a transatlantic rift by imposing trade tariffs, forcefully accusing allies of spending too little on defence, and threatening to withdraw US troops stationed on the continent. This has created uncertainty among North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies over whether the US would fulfil its obligation to come to any member’s aid if they were attacked.

Looking back at Locarno, said Zala, the “lesson [for] Europe is to take its security into its own hands.”

It’s now heeding that call. European Union member states are increasingExternal link their defence expenditures, with many even committingExternal link to allocating 5% of GDP to defence by 2035 – up from the current 2% target – at a NATO summit in June. There’s also talk of pooling a nuclear deterrentExternal link independent of the US, and boosting European countries’ defence industries to reduce their relianceExternal link on American military equipment and technology, which has included fighter jets, missiles and artillery.

More

Renewed controversy in Switzerland over US fighter jets – explained

A multilateral approach

Locarno’s formula for achieving peace is also instructive. In 1925, Europeans worked out their differences jointly instead of resorting to bilateral fixes.

“It was an attempt to end the balance-of-power politics as the key logic of international diplomacy, and replace it with something more attuned to cooperation,” said Jackson.

Fast forward to 2025, and the US is not only casting doubt on collective security but it’s also “deeply suspicious of multilateral institutions”, said the Glasgow professor. Trump prefers the kind of bilateral deals that lead to “powers in adversarial positions”, he added.

Germany’s Third Reich undid the multilateral system by signing individual agreements that it never intended to honour, Jackson noted. Coming after tit-for-tat trade protectionismExternal link following the 1929 Wall Street crash and economic downturns in the US and large parts of Europe, the events ultimately contributed to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

“Once again, we’re seeing the same kind of turning inward and tariff barriers going up – all the things that deepened the global economic crisis in the 1930s,” said Jackson.

An indivisible European security system

Locarno itself also offers lessons of what to avoid.

One of the Pact’s major flawsExternal link was its silence on Germany’s eastern borders with Poland and Czechoslovakia, which effectively left Eastern Europe out of the regional security arrangement. German political leaders took advantage of simmering territorial disputes with these new nations. In 1938, Hitler demandedExternal link that Czechoslovakia hand over the mainly German-speaking Sudetenland, pushing the continent closer to conflict.

Nearly a century on, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, eight years after the annexation of its neighbour’s territory in Crimea, has belatedly awakened Europe. “We in Germany ignored the warnings of our Baltic neighbours about Russia for too long,” Chancellor Friedrich Merz saidExternal link in June. “We have recognised this mistake.”

More

Our weekly newsletter on geopolitics

“It seems that European policymakers have understood that security is not divisible and that Ukraine’s security is an element of European security,” said Jackson.

Trump’s repeated delaysExternal link in US military assistance for Kyiv have seen European capitals double downExternal link on pledges to shore up Ukraine’s defences. They’re also looking ahead, with France and Britain proposingExternal link a “coalition of the willing” to support the Eastern European state after a ceasefire, though avoiding a specificExternal link troop commitment.

Switzerland and the ‘Spirit of Locarno’

As an attempt to restore political stability and rebuild economies after the war, the Locarno Pact was a positive development for the host state, Switzerland, said Zala. The Pact promised the reintegration of Germany, one of its most important trade partners, into Europe. “To have peace in Europe and stable neighbours is the best thing for developing one’s economy,” said the historian.

As a neutral country, Switzerland did not participate in the Locarno talks, but its foreign policy today reflects the spirit of cooperation and collective security they embodied. Peace promotion is inscribed in its constitution.

Last year the country, which so far has given CHF5.16 billion ($6.4 billion) of assistanceExternal link to Ukraine, hosted a conference on the prospects for peace in Eastern Europe. Though not a member of NATO, it depends on the alliance for its security and participates in joint exercises.

More

Switzerland and NATO: just flirting or the start of a wild marriage?

The concept of arbitration at the heart of the Locarno Pact remains a key element of Switzerland’s role on the world stage, with the Alpine nation often serving as a mediator to resolve conflicts between states.

But amid growing great power rivalry and global economic uncertainty, the rules-based order that Switzerland prizes is at risk, said Jackson. Although the efforts in the city of Locarno 100 years ago didn’t prevail in the decades that followed, the professor is convinced it’s the best route to peace today.

“[Locarno] envisioned law as a source of security,” he said. “It was one of those hopeful moments in international politics – a new way to settle differences peacefully.”

Edited by Tony Barrett/vm/ac

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.