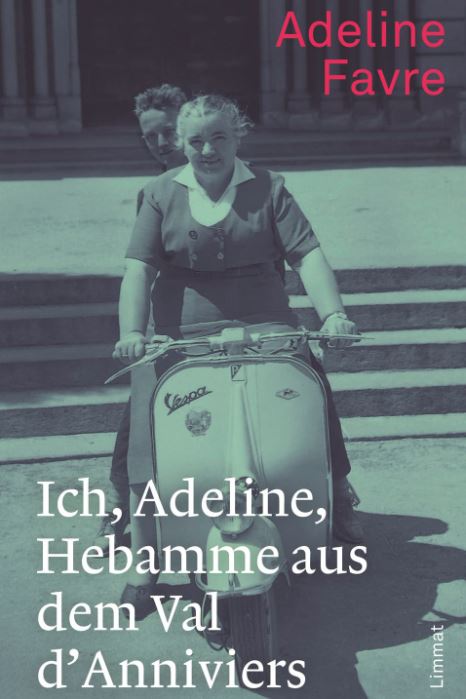

Tales from a legendary Swiss midwife

Adeline Favre from Val d’Anniviers in southern Switzerland attended over 8,000 births from 1928. The story of her life is also the history of her home canton of Valais in the 20th century.

The fact that Adeline survived her own birth was anything but a matter of course. When her mother gave birth to her in May 1908, having children was still a risk.

Doctors were rarely present. And while midwives were there, they were often powerless.

“From a practical point of view, doctors understood much less about childbirth than the midwife,” explains Hubert Steinke, head of the Institute of Medical History at the University of Bern. “Midwives used their hands, while doctors increasingly relied on devices like forceps, even for normal births.”

From the village to the big city

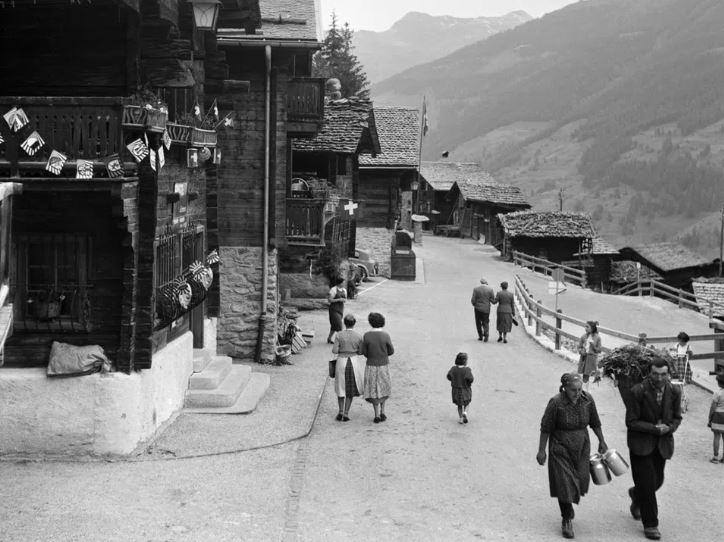

Adeline was the eighth of 14 children. She was born in Saint-Luc in the Val d’Anniviers valley, where the slopes are steep and the roads are narrow. There were hardly any cars back then. The people in the village mostly worked in farming, and life was hard.

Midwives were very respected. This was at a time when very few women gave birth in hospital. That made an impression on Adeline. Against her parents’ wishes, but with the blessing of the mayor and the priest, the 18-year-old went to midwifery school in Protestant Geneva.

She was naïve, she recalled in a radio interview in 1982: “I had no idea what I was getting into and my head was full of taboos”.

Two years later she returned to Valais with a lot of theoretical knowledge and a midwife’s bag. From then on, she went from house to house, visiting pregnant women around the clock.

Modern and warm manner

“It was exhausting, she was always on her feet. At the same time, she had to adapt her hospital training to home births,” says historian and midwife Kristin Hammer from the Zurich University of Applied Sciences.

Adeline saw herself as a modern midwife. She focused on hygiene and wanted to prevent infections. In doing so, she encountered traditional, Catholic mentalities in the remote mountain region.

While her modern views were not always well received, her warm manner was. At that time, many women worked until the last moments of pregnancy. It was not uncommon for them to go back to the barn to milk the animals even after their amniotic fluid sac had ruptured.

Second female driver in Valais

In 1932, Adeline married her neighbour Louis Favre. The couple lived in Sierre. The marriage remained childless, but it seemed quite equal, says Kristin Hammer.

Louis often accompanied his wife to her appointments. He drove her back and forth between the women in labour and protected her when men came too close. With his support, the midwife learned to drive in 1938. She was only the second woman in Valais to do so.

Increasing anonymity

After the Second World War, people’s everyday lives changed rapidly. A spirit of progress had swept through the land. In particular, the discovery of penicillin, which was used as an antibiotic in hospitals, saved many lives.

Adeline Favre worked more and more often in the hospital in Sierre. She was receptive of the changes and continued her education and training.

At the same time, she regretted the increasing anonymity in the field of obstetrics and that she had less and less to do with the families for whom she was caring. “Over time, we progressively had to leave the births to the doctors,” she said.

The midwife, who for decades was almost crushed by the sheer amount of responsibility, had to hand over more and more responsibility. Nevertheless, she continued to work in the hospital well beyond retirement age. In 1983 she passed away at 74 years old.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.