Why Switzerland is an archaeological treasure trove

Using the remote-sensing method Lidar, archaeologists can now uncover secrets that have remained hidden for centuries. No other country offers such comprehensive, freely available, high-resolution radar scans.

Hardly anywhere in densely populated Switzerland hasn’t been shaped by humans. Roads, houses and farmland characterise the landscape. Even the forests, which cover a third of the country, are cultivated.

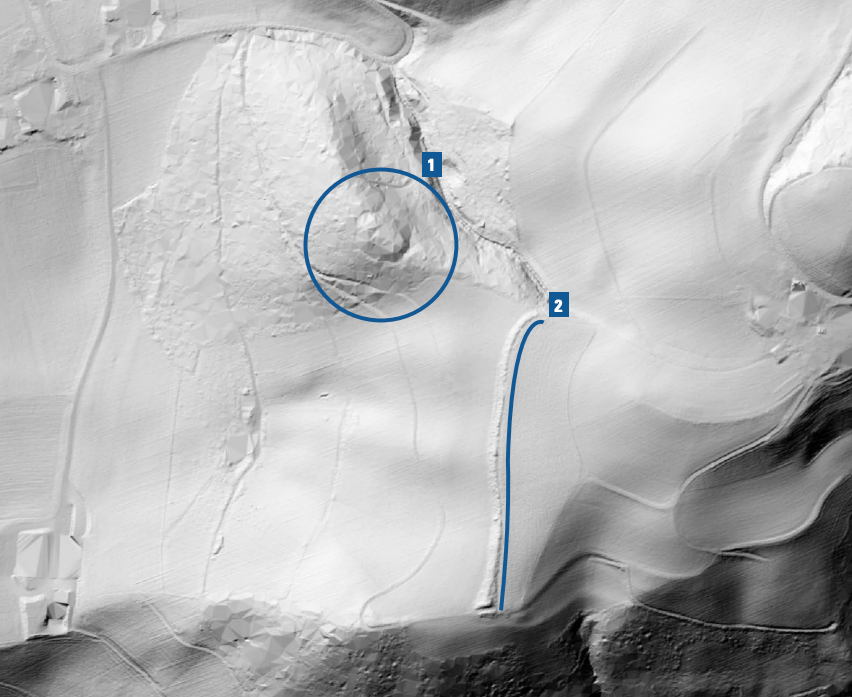

Nevertheless, they are also refuges of the past: archaeological treasures lie dormant here, between humus and roots. Lidar can visualise these remnants. It is a technology that can scan entire landscapes at ground level and thus create precise terrain reliefs.

Lidar stands for Light Detection and Ranging and is used from the air. An aeroplane or drone emits laser beams that hit the ground and are reflected back. Sensors measure the time of flight of the beams and use this to calculate the height and structure of the landscape. Vegetation can be masked out in the process.

More

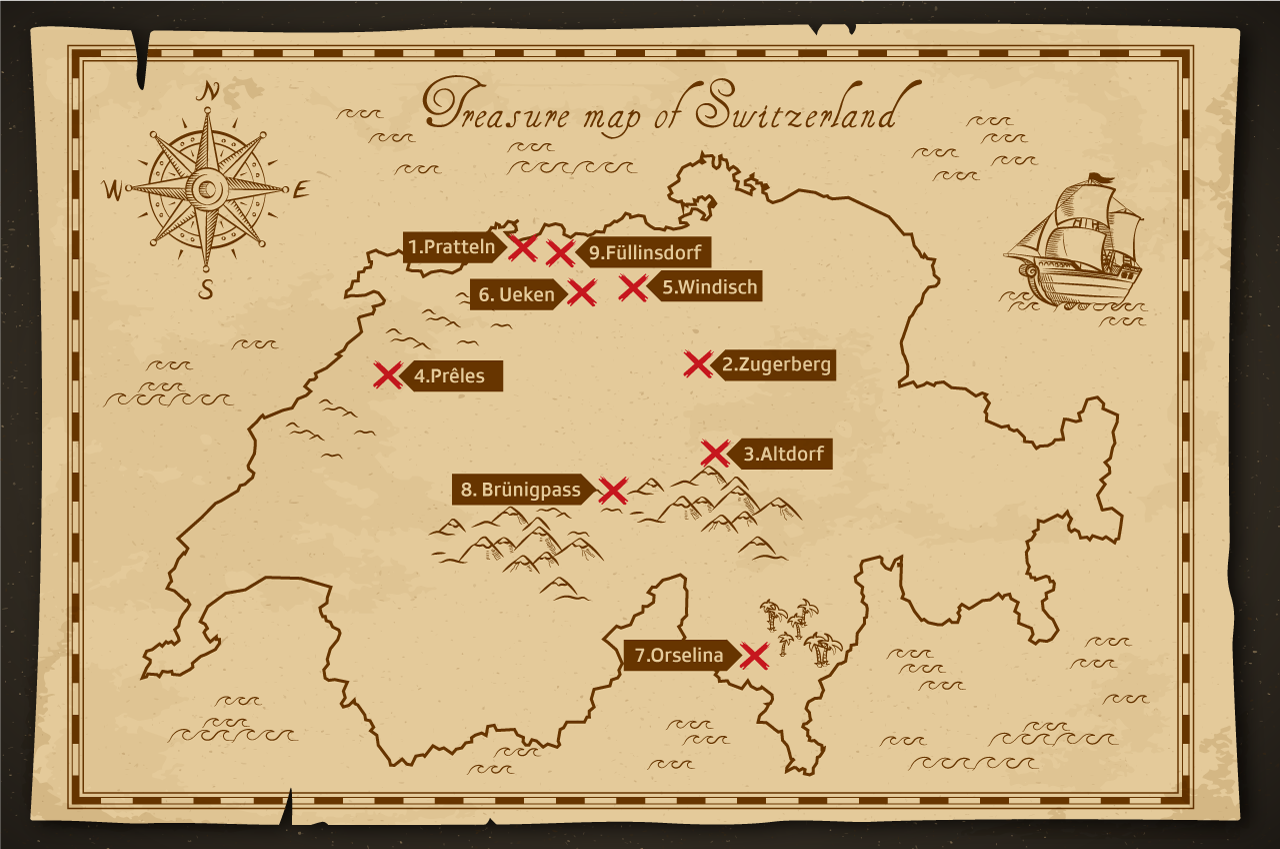

Discovering Switzerland’s buried treasure

Switzerland is a pioneer of this technology. The Federal Office of Topography (Swisstopo) has been mapping the entire country with Lidar since 2017. This mapping has now been completed and the data sets can be downloaded for freeExternal link from the Swisstopo website.

Focus on the forests

“Lidar data is also freely available in other countries, but high-resolution, nationwide coverage like that in Switzerland is unique,” says Swiss archaeologist Gino Caspari, who emphasised the advantages of the technology in a scientific publicationExternal link. Since then, he has been promoting its use in Switzerland.

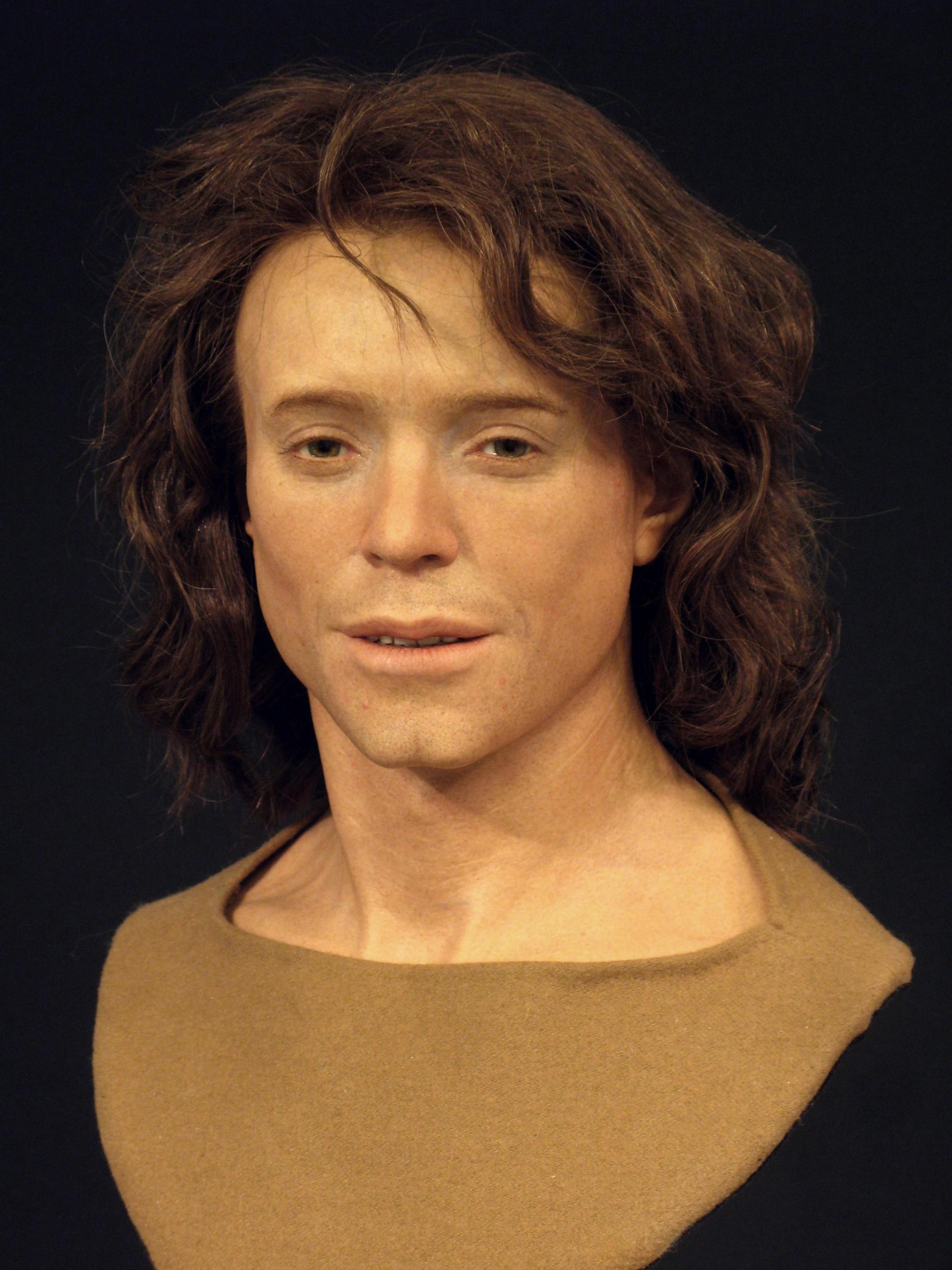

Caspari wrote that Lidar could help overcome so-called forest bias – archaeological excavations are usually triggered by construction projects, which means that most sites are located in urban or agricultural areas.

More

Facing up to Switzerland’s Roman past

Thanks to Lidar, however, it’s possible to look beneath the treetops. Like sunlight penetrating through the canopy of a forest, the laser beams also reach the ground.

Specialised software filters out the data points of the vegetation. The result is a detailed 3D profile of an area of the forest floor that can be viewed from all perspectives.

Artificially created mounds, which could contain an old grave, or rectangular structures, which could be the foundations of a ruin, become visible.

More

The Swiss metal detectorist who helped find a Roman military camp

Spectacular finds

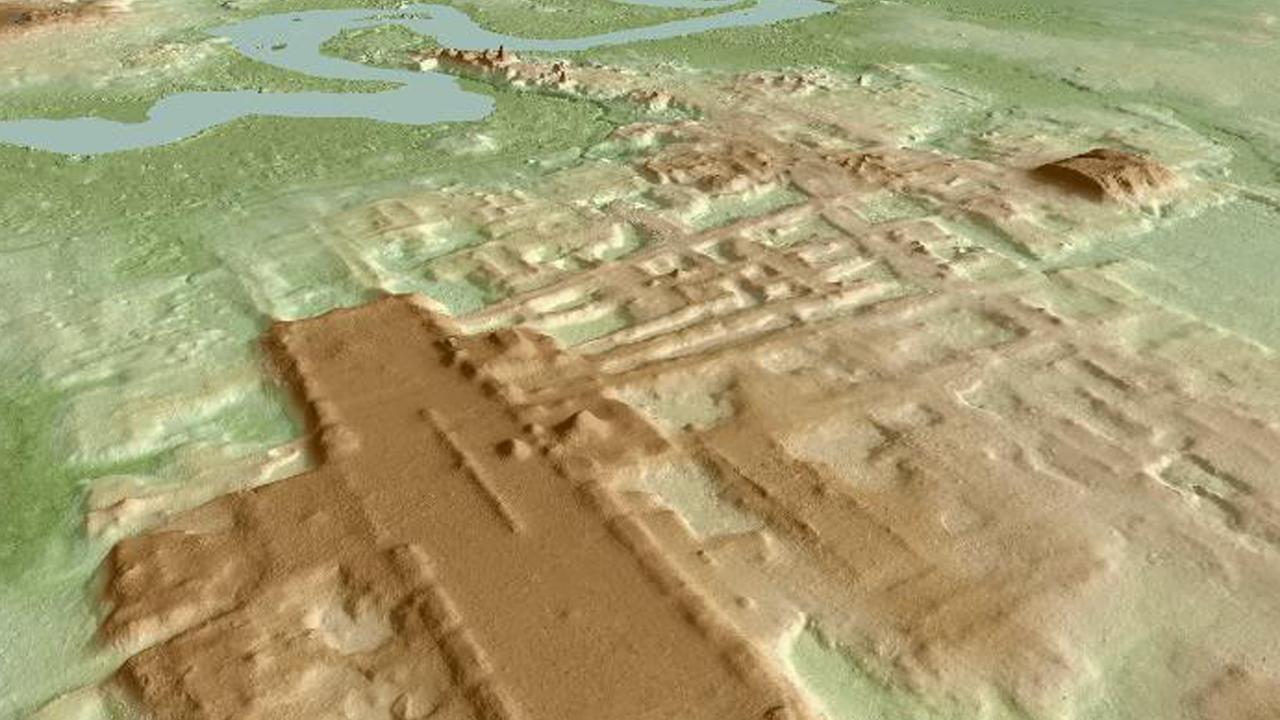

The technology also became known worldwide thanks to spectacular finds of the remains of ancient civilisations previously hidden in the jungle.

For example, in the rainforest of Guatemala, where former Mayan settlements appeared in relief, or in Cambodia, where a massive structure of an ancient Khmer settlement appeared in the landscape scan.

The first Lidar applications also delivered good results in Switzerland. In 2016, such maps led to the discovery of an unknown castle siteExternal link in the Emmental valley. In 2020, Lidar data revealed the true extent of a Celtic villageExternal link in Roggwil, Bern.

Caspari himself has not yet made any archaeological discoveries with Lidar in Switzerland, but he has used the technology abroad.

“In a remote region in Norway, we found countless Stone Age pit houses thanks to Lidar, which paint a completely different picture of the prehistoric landscape,” says Caspari, who has made a name for himself primarily through excavations in Central Asia.

He says he is fascinated by the potential in Switzerland and can well imagine realising projects here in the future.

Lidar is just the beginning

Lidar is promising, but on its own it is of little use. “It’s always important to confirm or reject these discoveries on site, as it’s easy to make mistakes even with good data,” Caspari says.

Artificial intelligence can also help by analysing the huge amounts of data. “Deep learning models have the potential to automatically identify archaeological structures,” he explains. “But such methods require extensive training data and specialised knowledge.”

And so it’s a question of money whether and how extensively this free Lidar data will be used for archaeological projects in the coming years.

“What’s missing so far is large-scale analysis. This in turn requires financial resources, and these are often hard to come by in archaeology,” he says.

Meanwhile, technology continues to advance with tools that, unlike Lidar, can also look beneath the earth’s surface.

“Ground penetrating radar and electrical resistivity measurements enable direct investigations of underground structures, and drone-based geomagnetics will certainly revolutionise archaeology once again,” Caspari predicts.

What is certain is that Swiss archaeology has an exciting future. The tools are available, the knowledge is growing – and if the authorities and institutions have the will, new, potentially ground-breaking discoveries can be made.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Adapted from German by Thomas Stephens

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.