Swiss university takes on gender bias in medical schools

Medical research and education have long been criticised as “gender blind”, “male biased” or made by men for men. To make future doctors fully conscious of gender issues, the University of Lausanne has become one of the handful of institutions worldwide to incorporate gender into medical education.

Carole Clair and Joëlle Schwarz, joint heads of the Medical and Gender unit at the University of Lausanne’s Centre of General Medicine and Public Health (Unisanté), want aspiring doctors to know about gender differences. Women and men have different risks for certain diseases and often experience diseases differently, which can have a fundamental impact on how a disease is diagnosed and treated. Yet medical schools rarely address sex and gender in their curriculum except for when teaching reproductive health.

Gender bias usually refers to unintended, but systematic, neglect of either women or men, with serious, negative effects on medical diagnoses and on the quality of healthcare people receive. For example, women are less likely to be given painkillers for the same pain men are experiencing, and lacking awareness of women’s heart disease may lead to doctors delaying the diagnosis of their patients.

Clair and Schwarz recognise that gender differences have long been overlooked in medicine, even in countries with a high standard of education like Switzerland. They want to change this, one university at a time.

Gender stereotypes, even among medical students

Already in 2017, Clair and colleagues conducted a pilot study with colleagues to assess gender sensitivity and the presence of stereotypes among medical students at the University of Lausanne.

They found that while the students showed a certain level of interest in the topic of gender in medicine, they were generally guided by stereotypes and tended to take the male perspective as the norm in clinical practice.

Schwarz notes that gender-based stereotypes among medical students unconsciously come into play in the early diagnostic process, when gathering important information from the patient’s medical history. Medical students had a tendency to explore more psychosocial aspects in the case of female patients and attribute their symptoms to psychological or subjective causes. In contrast, they were inclined to ask male patients specific questions that point to pathophysiological thinking and medical professional sphere.

A typical case where gender differences are neglected is pain management. Clair says a considerable proportion of medical students and doctors believe that women’s pain is more likely of “psychogenic” or “emotional” origin – women are seen to dramatise, overemphasise or even fabricate their experiences of pain. This could lead to physicians recommending psychological treatment rather than painkillers.

More

How gender disparities impact health

Such biases and misconceptions of female patients could ultimately influence the decisions medical students make in their future clinical reasoning, diagnosis and treatment, leading to questions over whether women are receiving optimal treatment.

Leading the way in Switzerland

Clair and Schwarz feel the time is right to take on misconceptions and stereotypes around sex and gender in medical education.

Their team was awarded a grant by the University of Lausanne in 2019 to introduce courses on the influence of sex and gender on health into the medical curriculum at Unisanté. The pilot project aims to integrate a reflective approach to the students’ medical practice. It’s the first such attempt in Switzerland.

“What is very innovative in this approach is that we use real clinical cases, while other similar projects carried out in the Netherlands, Germany or Sweden focus on theoretical courses on gender and medicine,” says Schwarz.

The need for gender perspectives in medical curricula has been acknowledged at a governmental level in the Netherlands and Sweden.

The Dutch Ministry of Health initiated a nationwide project for incorporating gender issues in medical education at Radboud University, Nijmegen medical centre, between 2002 and 2005, and then extended it to other universities.

The Swedish government has initiated several assessments of education about gender in medical schools, which have affected local university policies. In 2001 Umeå University medical school decided to mainstream gender perspectives into the medical curriculum and a committee was set up to lead the work. Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet was the first in Europe to establish the Web-based educational course “Health and Disease from a Gender Perspective”.

Gender medicine-specific training is offered at some medical schools in Germany, Canada and the United States as well, but it has not yet become a national effort.

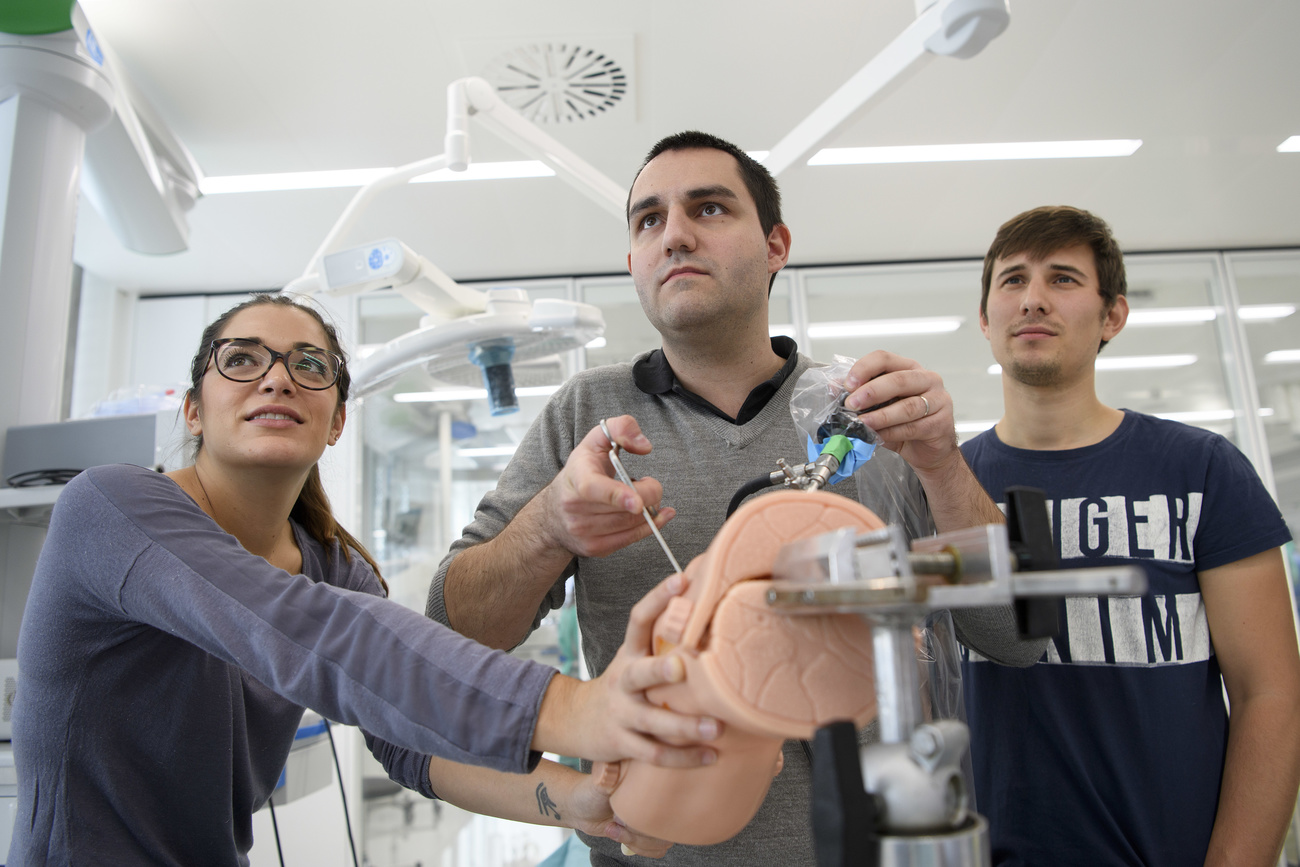

As part of the pilot curriculum at Unisanté, medical students have to spend a whole week in a clinic diagnosing and taking care of patients.

After clinical practice, each student must present a concrete medical case to a physician and a gender medicine expert from Unisanté and discuss what role the patient’s sex played.

The students then receive feedback from the expert and reflect on clinical reasoning by answering questions like, “If the patient had been a female, or vice versa, how would the diagnosis and offered medical care have differed?”

Schwarz explains that it allows the students to identify their own unconscious biases in diagnosis and treatment, and to avoid or minimise them in future clinical practice.

Clair and Schwarz hope to take their initiative nationwide. Last year they drew up a proposal in collaboration with the main Swiss medical schools to integrate gender into the curriculum of all Swiss medical schools and received funding from the umbrella organisation Swissuniversities.

“I think that is a sign of recognition of the effectiveness of our approach,” says Schwarz.

The team is constructing an electronic platform to share all pedagogical material and reference documents from all medical schools in the country. This is also intended to encourage their peers to lobby for compulsory teaching in gender-specific medicine at their own universities.

Gender is a scientific issue

Although the need for raising gender awareness has been discussed for decades, few medical schools around the world have successively put initiatives into practice.

Carole Clair believes that one challenge facing medical schools is the entrenched idea that gender is political or ideological and shouldn`t be considered a scientific issue. Even within medical schools some teachers still consider gender differences a tangential issue in education. They aren’t willing to make major adjustments to existing curricula or spend time instructing their students in the subject matter, she says.

Medical education covers an extensive range of topics and methods so it can be challenging to add new contents. Clair notes that “it was a very long process to sensitise our colleagues to the problems and to convince them to include gender perspective into teaching contents”.

However, in Switzerland gender-specific teaching is receiving a positive response. The Unisanté team is pooling resources and developing education material together with other medical universities in order to integrate sex and gender in the Swiss medical curriculum.

More

Innovation in women’s health comes in small doses

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!