How Swiss tunnel technology is controlling pollution a continent away

Throughout Latin America, pollution from transport and machinery has been adding to greenhouse gas emissions while causing growing health issues. A Swiss programme based on technology developed for trans-Alpine tunnels has helped Chile become a leader in addressing vehicle smog.

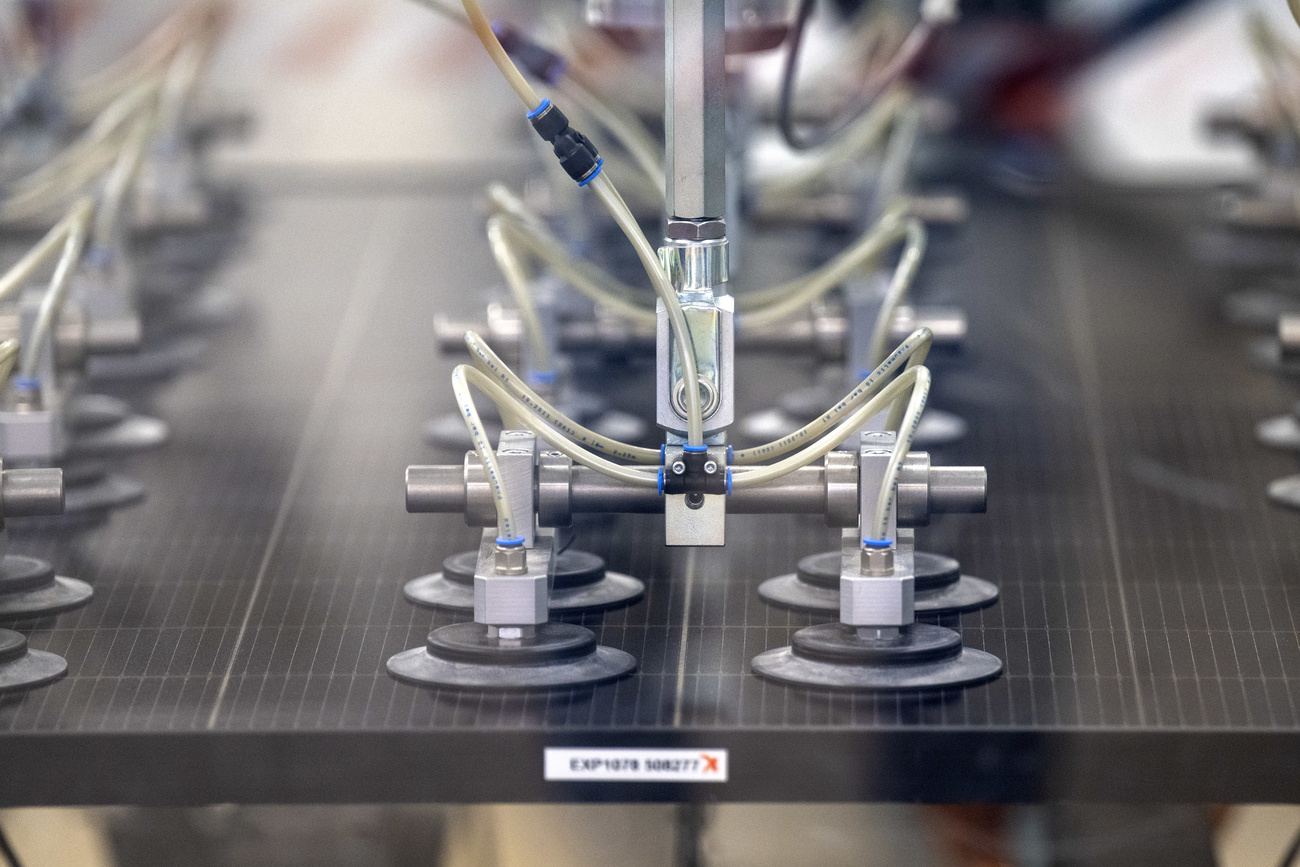

On a recent afternoon in a suburb of the Chilean capital Santiago, a group of government experts met at a construction site. They were there to see an excavator fitted with a filter to reduce ultra-fine particle emissions, or black carbon. A new measuring device was about to give its first precise readings on the filter’s performance.

“Look at that number,” exclaimed Stamios Pothos of TSI, the US manufacturer of the measuring device. The excavator, he said, was now outputting fewer particles than the background pollution level in the air, meaning that the filter was “doing a good job”.

The filter is part of a Swiss-supported programme known as CALAC+External link which aims to lower emissions in four Latin American capitals by introducing soot-free engines in public transport and off-road machinery, such as excavators used in road construction or other public works. In addition to Santiago, the project also operates in Bogota, Mexico City and Lima.

Longstanding cooperation

In Switzerland, such filters to cut emissions from ultrafine particles began to be implemented in the early 1990s. The technology was originally developed to counter toxic pollution generated during the construction of trans-Alpine railway lines, as the first of its kind in the world.

Chile has struggled with the fallout from such particle pollution for decades, with its capital located in a valley between high mountains that traps emissions. In 2011, the concentration of black particle pollution in Santiago was on average 60 to 100% higher than the national air quality standard and World Health Organization standards. The city regularly experienced 24-hour bouts of exposure to black carbon 200% above that level.

Chilean authorities began to take an interest in the Swiss filter technology in the mid-1990s.

An initial project was hatched by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in discussions with the Chilean government to introduce clean technologies in the Transantiago public bus network based on Swiss know-how. With smoke billowing from their tailpipes, the capital’s public transport buses were among the most visible emitters of black carbon.

A team of technicians, including Rodrigo Tapia of the Chilean transport ministry, visited Switzerland in 2003 to observe the use of diesel particulate filters in buses.

“We were pioneers in Latin America regarding the use of filters,” he says. “Particulate matter filters were unknown. There was no fleet maintenance or regular checks. Not even the manufacturers were prepared for the changes to come.”

Adapting for the region

Nancy Manriquez, mobile source manager at the Chilean environment ministry, thinks that “successful cooperation” with Switzerland was responsible for the passage of pollution regulations for buses in 2010.

But getting filters installed on the smoky buses was initially complex.

Robert Fraser is the CEO of Purexhaust, a certified supplier of the filters who has long worked with the Chilean environment ministry. He said a pilot project was introduced when vehicles importers argued that the filters would not be effective.

Meanwhile, some private operators of public buses opted to invest in new vehicles already fitted with the emissions-cutting technology due to the high cost of retrofitting. Diesel filters for buses vary in price between approximately $5,600 and $8,100 (CHF5,500 to CHF7,961). Other operators who could not afford either option were incentivised to fit existing vehicles with the devices with offerings to extend their permits to run buses.

Santiago’s public transport operator has since increased to 3,256 the number of buses which are equipped with filters, including retrofits and those imported with the equipment already in place. Some 390 buses also run on electricity, making the urban network the largest fleet of electric buses in any city outside of China.

The next goal is installing more filters on off-road vehicles, such as those used for road construction. Such machinery contributes 17% of the particulate pollution in the Santiago metropolitan area. Elsewhere in the world, off-road vehicles have become the latest focus of more stringent regulations, with the diesel particulate filter market expected to grow by 11% by 2025.

While Chile announced that all larger construction machinery contracted by the public works, housing and health ministries must be fitted with particulate filters, only two, including the excavator in the recent demonstration, are currently fitted. Manriquez of the clean air division says fitting all of them with filters amounts to “a great challenge” that has never been done before.

There’s also the question of whether the filters are working. Manriquez says her country is currently lacking a system to accurately detect emissions on filter-fitted vehicles in use.

Local consultants at Swisscontact, a Swiss foundation for international development, have been helping the Chilean government to find a solution for detecting faulty filters.

Public opinion

Before widespread street protests in Santiago led Chilean President Sebastian Pinera to cancel the city’s hosting of this month’s United Nations’ COP25 climate summit, the government had accelerated its climate change mitigation plans – including CALAC+ – which it had hoped to highlight at the conference.

But some worry that the political crisis may have put in question the future of such plans in Chile. Referendums scheduled for 2020 will ask citizens if they favour the rewriting of the country’s Pinochet-era constitution which instituted a free market system over the management of social services.

Sparking the protests was a government decision, later reverted, to increase fares on Santiago’s subways.

“People may have thought that the development of environmental standards was too quick,” says Mark Untersander, the Swiss embassy’s trade officer who also coordinates international cooperation projects in Chile. “Some people argued, ‘Why should you care about plastic bags when there is no education?’”

But at the transport ministry, Tapia is confident that sustainable transport will continue to move forward despite political uncertainties.

“Everyone is strongly aligned on what needs to be achieved,” he said.

Untersander agrees. He thinks that the country’s success with the CALAC+ programme has helped countries in the region learn from each other’s experiences while challenging the common belief that Chile is slow to adopt new technologies.

“They would say, “Of course it works in Switzerland, but it could never work in South America’”.

This project, he says, is proving them wrong.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.