Asylum seekers to hand over smartphones before entering Switzerland

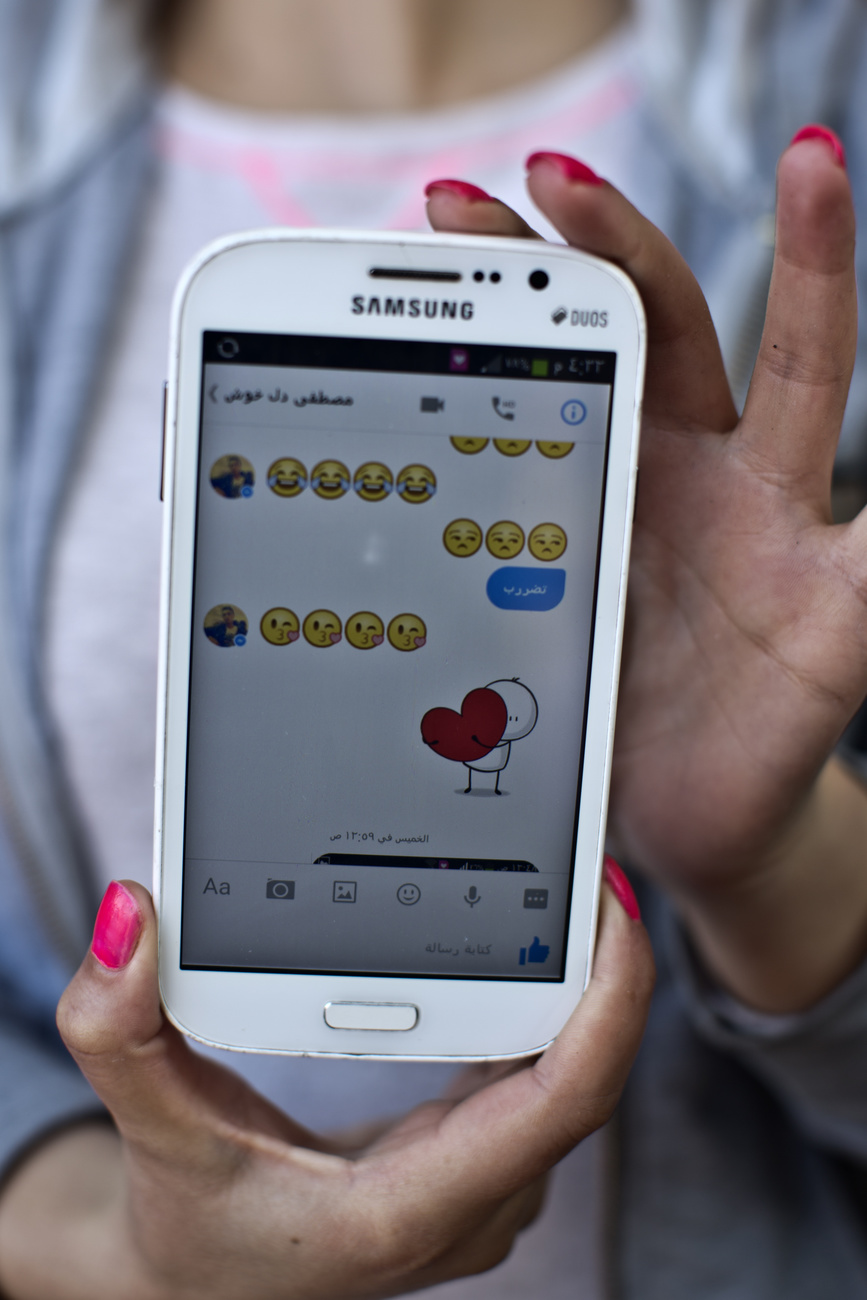

Switzerland is set to join the ranks of countries that search through private smartphone data to verify the identity of asylum seekers.

On September 15, the Swiss parliament agreed to allow the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) to access asylum seekers’ mobile data if it is the only way of verifying a person’s identity.

The move means authorities will be able to sift through data held on telephones, computers, tablets, or smart watches. Information gathered via a digital program will be stored on a secure server for one year.

Most people who request asylum in Switzerland enter without documentation that proves their identity. The new law hopes that access to smartphone data will allow authorities to find the age and country of origin of the asylum seekers. There is no official implementation date set as of yet.

“It’s absurd that authorities trying to establish a person’s identity have to proceed blindly, without having the right to take into consideration devices which contain large amounts of information,” argues the architect of the new law, Gregor Rutz from the right-wing People’s Party.

During the parliamentary debate, justice and police minister Karin Keller-Sutter insisted the measure could only be used for the purposes of identification.

“Various safeguards have been put in place to avoid abuse and assure privacy is respected,” she said.

Assault on privacy

Refugee advocates are scathing in their assessment of the new law, which is not subject to control by the courts, as is the case in when it comes to monitoring people who have committed serious crimes.

“The measure is disproportionate and constitutes a serious attack on the right to privacy,” says Swiss Refugee Council spokesperson Elian Engeler.

The new law has also been criticised by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Although it recognizes the need for states to identify people who arrive in their territories, the UNHCR says complete access to personal information amounts to a major assault on the right to privacy, which is protected both under international law and by the Swiss constitution.

“Such an intrusion is admissible only under certain conditions, which this law does not fulfil,” says Anja Klug, head of the UNHCR’s Switzerland and Liechtenstein office.

More

What’s the best way to distribute asylum seekers in Europe?

She argues that searching mobile phones is not an appropriate method of establishing an asylum seeker’s identity, nationality, or itinerary.

“When people flee, mobile telephones can be used by several people, including by traffickers. That could make it difficult to attribute the data to one person.

Electronic proof could also be easily altered or destroyed,” says Klug.

International reaction

Switzerland’s new law falls in line with what other European states are implementing.

Following the 2015 migration crisis, several European countries including Germany, Denmark, Belgium and Austria began searching the mobile phone data of people subject to asylum proceedings. But the practice has attracted broad criticism both from NGOs and political parties. Belgium and Austria did not implement the law due to data protection issues.

In Germany, the practice of searching migrants’ mobile phones has been legal since 2017. But there too implementation has proved difficult.

In June, a Berlin administrative court ruled the practice illegal in the case of an Afghan asylum seeker who did not have her passport when she requested asylum in 2019. To check that the migrant was indeed an Afghan national, immigration agents confiscated her smartphone to analyse its data. A month later, her request for asylum was rejected.

Supported by privacy advocates, the asylum seeker filed a complaint and won her case. The presiding judge ruled that Germany’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) had broken the law by unnecessarily storing information obtained during its search. The case could now be referred to the Federal Constitutional Court, which would have the power to overturn the 2017 law. Two other migrants from Syria and Cameroon have made similar complaints.

Mattias Lehnert, a lawyer specialising in migrant rights, believes the cases could push German authorities to review their methods.

Costly and ineffectual

Aside from the ethical and legal questions, the usefulness of this type of search is also disputed by experts.

A study published in December 2019 by the German Society for Civil Liberties found that information gathered had helped to confirm a person had lied about their identity in just one or two percent of cases. In a quarter of cases, searching a telephone or another device failed for technical reasons. The rest of the time, the data simply confirmed the migrant’s story.

“Evaluations undertaken in Germany show that the benefit is small in relation to the effort required to examine the data,” says Klug.

The study also examined the cost of equipment and digital programs necessary to analyse the data. Between 2017 and April 2018, Germany spent €7.6 million (CHF 8.4 million), double what the program was initially expected to cost, it found.

More

UN migration pact to be scrutinised by parliament

Guinea pigs?

Lehnert is adamant that searching the digital devices of migrants is pointless.

“Governments are using it to intimidate people who seek asylum,” he says. He is also worried that these technologies will be used for other purposes, to check up on other population groups.

“Asylum seekers are being used as guinea pigs to test new technologies for control and surveillance,” he says.

Authors of the German study, journalist Anna Biselli and lawyer Lea Beckmann, agree.

“The BAMF’s approach is part of an international trend, which consists of testing new technologies of control and surveillance on refugees,” they write in their conclusion. “The expansion of these technologies for other uses and for other parts of the population remains a threat.”

In Switzerland, with the law approved by parliament, NGOs are now waiting to see how it will be implemented.

“The law has not been thought through. It contains imprecisions and gaps. We will closely observe how it will be implemented,” says Engeler from the Swiss Refugee Council.

More

Asylum seekers in Switzerland need more protection experts say

Translated from French by Sophie Douez; edited by Virginie Mangin.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.