The bizarre case of Youssef Nada and Switzerland’s role in the ‘War on Terror’

This is the story of how an Egyptian businessman living in an Italian enclave in Switzerland ended up in the crosshairs of the Swiss and American judiciary.

Villa Nada lies high above Lake Lugano, secluded and quiet. The view is breathtaking – from Lugano down as far as Monte San Giorgio; opposite, at eye-level, lies majestic Monte San Salvatore.

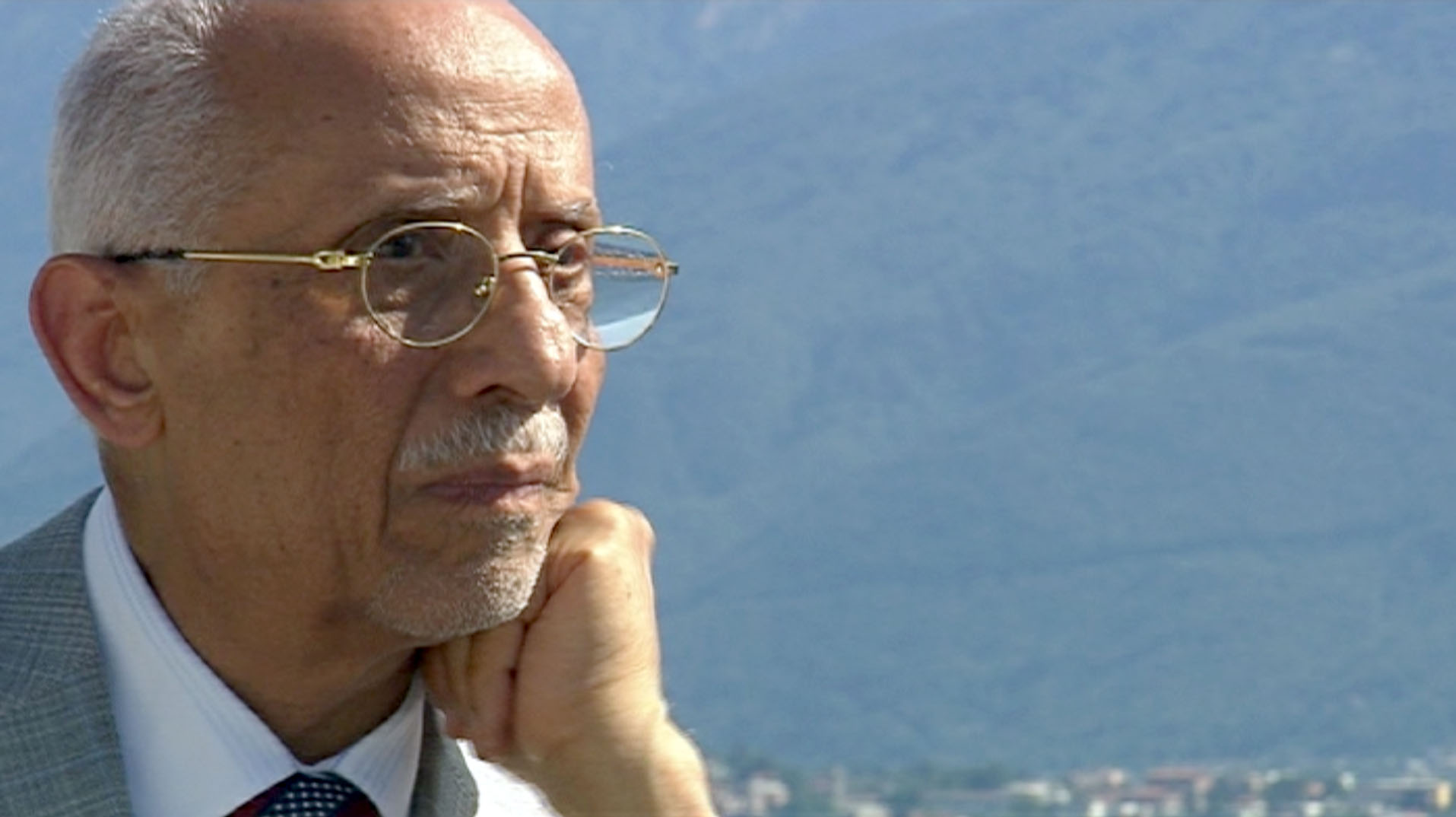

Youssef Nada ushers me into his study, where a pile of files sit on the table. They contain investigation files and official documents from several states, newspaper articles and bank documents. Nada likes showing them – and he shows them often. This year is the 20th anniversary of 9/11 and many journalists want to talk to him about his Kafkaesque story on how he was allegedly involved in the attacks. Even if his advanced age makes that harder than it used to be.

What does a man now aged 90 have to do with the most fatal terror attack of recent history? Nothing, as is now clear. But the view back then was – everything.

Just under a month after September 11, 2001, the first bombing in Afghanistan began. The United States and its allies hunted down not only terrorists in central Asia, but also their accomplices around the globe. The men suspected of financing terror behind the scenes were particular targets. Among them was Youssef Nada, his Bank Al Taqwa, and other individuals who had connections to the bank. The accusation: support for Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda.

On November 7, 2001, police units stormed his bank in Lugano and his villa in neighbouring Campione. While Nada was in discussions with the state prosecutor and the police – who were forensically searching his house in the presence of his family – US President George W. Bush gave a speech in Virginia. “Al Taqwa is an association of offshore banks and financial management firms that have helped al Qaeda shift money around the world,” declared Bush, adding that there was “solid and credible evidence” for this.

Youssef Nada looks back with a mix of outrage and incredulity. “It was completely crazy when that happened.” The president of the US had named his bank as one of the two main financiers of Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda on camera. “This public accusation was worse for me than all the other problems that emerged afterwards,” he said.

The shadow diplomat

Two facets of Youssef Nada’s life are central to this case. The first is his business activity. Born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1931, he first became prosperous in his native country by trading dairy products. He used this wealth to enter the construction industry. From the 1960s, it was a very profitable business, because after decolonisation oil dollars flooded into reconstruction projects in the newly founded states and building materials were urgently needed. “They called me the king of cement in the Mediterranean region,” Nada says, with a mix of pride and nostalgia. At his peak, he was doing business in 25 countries, he says.

He entered the banking industry later. The bank he owned and founded: Al Taqwa Bank, active in Islamic banking, has offices in Lugano, Liechtenstein and the Bahamas, among other locations. The institution suffered heavy losses in the wake of the big Asian crisis at the end of the 1990s.

The second facet is his membership of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. He joined this political and religious movement, which has representations across the Islamic world, at the age of 17. In some countries it is integrated into government, in others it operates underground. The Brotherhood has major influences, but has also suffered much repression in its almost 100 years of existence. As a youth, Nada experienced this himself physically when he was incarcerated for his membership. He spent two years in prison.

Soon after that he left Egypt, but he has remained in close contact with the Brotherhood all his life. “I am proud of being a Muslim Brother,” Nada says. “I have never made a secret of it, not then and not now.”

Nada is an engaging talker, polite and friendly with a distinguished appearance. It is not surprising that the Brotherhood has, over the years, asked him to intervene politically. As a major industrialist, he came into contact with the political scene early on: He got to know politicians, members of royal families and high-ranking bureaucrats. In the course of his life, he has obtained the citizenship of several Muslim countries; he later gained Italian citizenship. If the Muslim Brotherhood wants to transmit a message, Nada steps in. In Iraq, he spoke with Saddam Hussein, in Iran, with dissidents, and in Afghanistan with warlords.

And Nada also receives guests at his home. Some newspapers spread the idea that Villa Nada has developed into an unofficial foreign ministry for the Muslim Brotherhood. What is certain is that Nada receives many influential people in Campione, most of them from Muslim states – from North Africa to Malaysia. Private photos at his home confirm the diplomatic level of these meetings. He wrote about many of his encounters in his authorised biography. Sitting on the sofa with Lake Lugano in the background, he says laconically: “It was an eventful life.”

‘Financially destroyed’

But from autumn 2001, his villa became his prison – a luxurious but enforced one. From November 9, 2001, two days after the raid, his name was on a so-called United Nations terror blacklist. After a UN Security Council Resolution was issued against people and organisations with connections to “Osama bin Laden, the Al-Qaeda group or the Taliban,” he became an international pariah.

States are bound by these resolutions, including Switzerland. They had to block all funding and those listed were banned from travelling. Because Nada’s house is in the municipality of Campione, an Italian enclave in Swiss territory, he was virtually under house arrest for the following years – confined to an area of land just under one square kilometre in size.

The financial restrictions were even worse. “From one day to the next, I had no access to my money.” His bank was liquidated and suddenly he could no longer cover daily living expenses or his children’s studies. Nada doesn’t want to say more about this traumatic time for his family. His conclusion is clear. “I was financially destroyed,” he says. But not morally, he stresses.

A judgment in Egypt is almost a footnote to this story: “[Former President] Hosni Mubarak accused me of donating 100 million in support of terror organisations,” Nada laughs. “A joke.” Especially as he had no access to his accounts at that time. Despite this, in 2008 a military court sentenced Nada to ten years in prison in his absence.

Officially, the story ends on September 23, 2009. After eight years, Youssef Nada’s name was struck off the UN terror blacklistExternal link. There was no hearing and no reason was given. There was also no apology.

Although he was under investigation by intelligence agencies and legal authorities in five states, no charges were filed in connection with the UN terror list. There was certain satisfaction in 2012, however, when the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) came to the unanimous verdictExternal link that Switzerland had violated the European human rights convention with its strict application of the UN resolutions. A decade after 9/11, the ECHR process was the only court case relating to Nada.

More

Our newsletter on geopolitics

Grateful media

The story received considerable media attention because it was irresistible. A rich Egyptian industrialist, open about his membership of the Muslim Brotherhood, who headed an Islamic bank in Switzerland and influenced global politics from his villa in a mysterious Italian enclave. The man who secretly funded Osama bin Laden and his band of terrorists. The newspapers gobbled it up.

And how could they not? Nada was accused of funding terrorism by the highest echelons of the American political machine. The argument put forward by the American authorities – that a wealthy network of sympathisers must have supported the 9/11 attacks – was taken up widely. The media spread the idea that Al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden had access to a highly complex global financial system that funded their activities. The story of the “bankers of the holy war” (“Cash” magazine on 16.11.2001) – among whom the publication counted Youssef Nada – fitted like a glove.

Yet how little it actually required to carry out what was perhaps one of the most serious terror attacks in history seems absurd today. The American investigation into 9/11 concluded in 2004 that Al-Qaeda had spent about half a million dollarsExternal link on the attacks. Compared to the impact, this was a tiny sum.

In the feverish climate after the attacks and amid all the negative reports, Nada made himself available to the media and gave lots of interviews. “I never looked for media attention but I had to defend my reputation,” he says. He is still furious with some journalists who wanted to raise their own profiles with his case.

One particularly extreme situation was a document found in the raid on his house that featured in some media under the codename “The Project”. According to the media reports, it was the Muslim Brotherhood’s secret plan to undermine the west. Nada says this is not just nonsense; it is targeted libel. “I have received thousands of letters in my lifetime and they found this by searching through a pile of papers. And the Brotherhood should take responsibility for this?”

Nada sought out the official translation from the Swiss police. It notes that the document was written in 1982, that it is not signed and that no names are attached to it. “But of course they made a connection to the Muslim Brotherhood,” he says. “That’s typical.” This followed the narrative of one Egyptian military government after the other that declared the Brotherhood, the biggest opposition group, a terrorist organisation.

Why is this so important to him? In his authorised biography, the incident with the document takes up a lot of space. “This cultivated the idea of a masterplan to Islamize Europe,” Nada explains. It is notable that particular journalists – whom he names – energetically advanced this theory, he says. “You have to realise that these accusations were spread widely and seized on by numerous European intelligence services.”

Another accusation was even more serious: a journalist at the Italian daily newspaper Corriere della Sera wrote in the late 1990s that Nada had financed the Palestinian organization Hamas. The journalist maintained that he had been in contact with the FBI and, in sworn testimony to US authorities, explicitly linked the name of Youssef Nada and his bank to terror financing. Nada’s conclusion was that the media’s repetition of these accusations – which were afterwards picked up by numerous other media – influenced the American secret services and later served as a basis for his alleged connection to Al-Qaeda.

This cannot be verified. To this day, the information on which the American secret services based their evaluations is classified. Italian authorities investigated Nada, but he was never charged with terror financing, either before or after 9/11. He was involved in libel suits against Corriere della Sera for years – in 2011, the case was decided in his favour and he received financial compensation.

Nada says he has been attacked again and again in the wake of smear campaigns against the Muslim Brotherhood. For him it’s clear: “This entire business was a political decision to get me out of the way and stigmatize the Muslim Brotherhood.” He hints that he knows who was behind it. But he doesn’t want to comment on who exactly had an interest in this.

On the hunt

Who is a friend? Who is an enemy? After the September 11, 2001 attacks, George W. Bush used the following formula: “You’re either with us or you are with the terrorists.” That forced governments to take a position, although there was no real choice. As the hunt for terrorists and their accomplices began in the “War on Terror,” many deployed their full armouries. In the words of a former CIA officer: “After 9/11 the gloves came off.”

But where should the hunt begin? A report from the federal criminal police in January 2002 already made clear what the Swiss authorities were up against in the Nada case. “To put it frankly, many of the insights are based on supposition and cannot be proven by investigations so far,” he says. And then even more clearly: “Not the slightest clue that points to terror financing or support for terrorism has been found so far.”

The authorities, however, were under pressure. Switzerland was certainly acting in good faith, and not just in this case, says Jean-Paul Rouiller. He heads the Terrorism Joint Analysis Group at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) and, back then, he was involved in the Nada case as a police officer. “Our first instinct of course was to help the Americans as far as possible,” says Rouiller. The American authorities have always been perceived as reliable partners, he said.

For him it is clear from today’s perspective that the US overreacted after the attacks. But he does not agree with the argument that this overreaction was not based on intelligence. He doesn’t want to talk in detail about the Nada case. But he says the US and Switzerland have very different procedures for evaluating intelligence information: Switzerland’s approach is less politicised and rule-of-law considerations dominate.

It is also clear to Rouiller that at the time of 9/11, there was much less expertise available concerning Islamic extremism. “There were clear misconceptions,” he says. That was particularly true with regard to the Islamic banking business that Nada conducted. Financial instruments that comply with Islam are now also offered by western banks, but at the turn of the millennium they were little known – even by the investigating authorities to whom Nada appeared so suspicious.

‘An absolute scandal’

Dirk Marty, a former senator, chooses stronger words: “The story was an absolute scandal.” The fact that someone could land on a UN sanctions list without any kind of procedure, without ever being questioned, without knowing the exact accusations and without having an option to appeal. “I couldn’t believe it at first,” he said.

Marty is from the Swiss canton of Ticino and heard about Youssef Nada from a mutual acquaintance. “I met him not as a lawyer but in my role as a politician and human rights advocate,” says Marty. He quickly realised that there was no truth in the accusations. A former Ticino prosecutor, he had never before come across Nada’s financial institution, which by this time had been operating from Lugano for three decades.

It was Marty who encouraged Nada to file a complaint against the prosecutor’s legal investigation. “Nada didn’t want to at first. He thought it was not appropriate for him to take action against Switzerland, which he perceived as his host country,” said Marty. But Marty convinced him: “For the rule of law, this complaint was extremely important.”

Despite many legal uncertainties, the Federal Criminal Court ruled in Nada’s favour. The prosecutor had to drop proceedings against him in 2005. It took another four years for him to be struck off the UN sanctions list. The suit filed at the ECHR in Strasbourg mentioned above was also Marty’s suggestion. There, too, the main problem of UN resolutions became clear: these are higher laws that states must apply even if they contravene their own laws.

Marty considered it a scandal that an organisation like the UN, which is committed to democracy and the rule of law worldwide, could do something like this. But he has since got used to this situation. He gained insight into highly dubious incidents during the “War on Terror” from a different perspective. He was a representative at the Council of Europe from 1998 to 2011. His reports on secret CIA prison camps and the transfer of prisoners in Europe stirred up much excitement in the organisation from 2006 – and brought the subject of the infamous black sites to the attention of the media. “That was happening at the same time as the Youssef Nada story,” he says.

The outrage Marty felt at the time is still in his voice. He is also harshly critical of Switzerland. “None of the authorities had the courage to stand up to the Americans. They were also deliberately manipulated by the US,” he says. This became apparent in documents made public by Swiss public television. After an initial investigation, the federal lawyer in charge wrote to Washington saying that he was disappointed by the information provided. It was “superficial” and “unusable,” he wrote.

More

Egyptian businessman wins lawsuit against Switzerland

Marty points out that Nada was also removed from US terror lists. “This is an unambiguous signal. As long as there is the slightest suspicion about you, you stay on that list,” he says.

Switzerland managed to push through some changes to the blocked accounts and travel bans in UN sanctions. A ruling for hardship cases was introduced so that those affected can withdraw money to meet their living costs, and a de-listing process was created. This enabled listed people to have their status checked for the first time – this was not initially planned. The most important change, which Switzerland brought about in cooperation with other countries, was the creation of an independent ombudsperson’s office. Even though its influence is modest, it is a small correction to the sanctions committee which makes the relevant decisions. For Marty, this doesn’t go far enough. “Switzerland could have done considerably more,” he says.

Marty doesn’t want to discuss whether there was a conspiracy against Nada, as the latter has indicated. But he believes that the story has not yet been fully told.

What remains?

The UN lists led to no legal proceedings in Switzerland. In response to questions, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) responded: “So far, fewer than ten people and organisations in Switzerland have been affected by the UN Security Council sanctions against Al-Qaeda and the Taliban. All these people and organisations have no longer been subject to sanctions for many years, for example, because they were struck off the sanction lists.” The office gave no information on further details such as blocked assets.

The story of the UN terror lists is not over, even 20 years after 9/11. The ombudsperson’s office, which oversees them, still exists. Since 2018, it has been occupied by Daniel Kipfer Fasciati, who is Swiss – but only until the end of the year. A former federal criminal lawyer, he voiced serious criticisms when he handed in his noticeExternal link. He complained about the lack of institutional independence for his post and the contractual conditions for the ombudsperson. Basic elements are missing from the contract, ranging from diplomatic status – without which much is impossible at this level of global politics – to health insurance.

According to an articleExternal link in the magazine Foreign Policy, this is not by chance: a long report that also quotes Kipfer Fasciati’s predecessors makes clear that these hindrances are desired. As long as the member states in the Security Council do not decide otherwise, the ombudsperson only has limited influence. A shift is not in sight: the terror lists, which are created with almost no legal control mechanism, still seem to be a popular tool in the “War on Terror.”

And Nada? His work for the Muslim Brotherhood continues. During our conversation he received phone calls from Arab media, he is engaged in the cause of Muslim Brotherhood members under arrest in Egypt and he gets involved in public debate. But separately, he wants to enjoy his late years in Campione and no longer nurses a grudge. “After all, I managed to hold my ground against world power,” he says.

Swiss judge Daniel Kipfer spent three years as an ombudsperson overseeing the UN terror list mentioned in the text. Read our portrait of him here:

More

Refereeing the war on terror

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!