To cosy up to NATO, Switzerland may have to accept the bomb

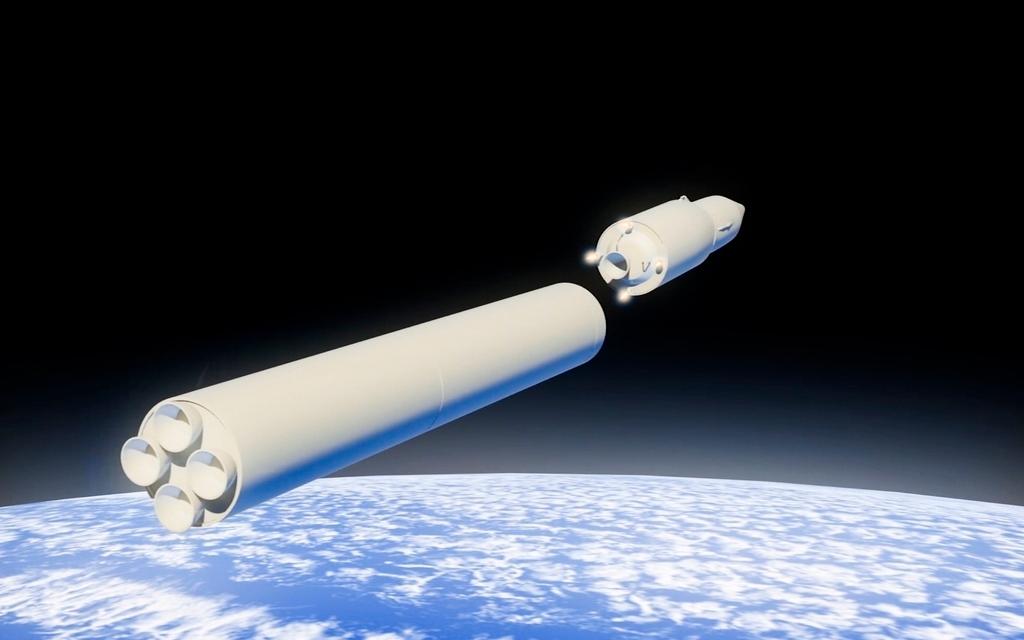

Switzerland aspires to work more closely with the Western defence alliance. But to do this, it must pay a heavy price: saying no, once and for all, to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Last March, Swiss defence minister Viola Amherd met NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg in Brussels. On the agenda was closer military cooperation. Russia’s attack on Ukraine has all but driven neutral Switzerland into the arms of the Western military alliance.

Being drawn under the NATO defence umbrella comes at a price, however. According to the newspaper Le TempsExternal link, Stoltenberg asked Amherd not to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The nuclear powers United States, France and Britain are thought to also be putting pressure on Switzerland to not join the treaty.

The TPNW was negotiated in 2017 by 122 states. So far 92 states have signed up and 68 have ratified it. All the nuclear powers were opposed to it, including NATO, which defines itself as a “nuclear alliance”.

This puts Switzerland’s political leaders in an awkward position on a host of issues.

What does the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons say?

The TPNW declares nuclear weapons illegal, and its ultimate goal is step-by-step disarmament, ending with a nuclear-free world. That was also the aim of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1970, which was initiated by the nuclear powers themselves (US, France, Britain, China and the Soviet Union). To this day the aspiration remains just that – an aspiration.

More

Government’s stance on nuclear ban under scrutiny

The slow pace of nuclear disarmament eventually led to the TPNW. At first Switzerland had supported the treaty. A year later, however, the federal government decided not to sign it for defence-policy reasons. Ironically, it was Switzerland that had initiatedExternal link the process which led to the TPNW, on the occasion of a review of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty back in 2010.

How does Switzerland cooperate with NATO?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine shook the framework of European security to its foundations. NATO, which French President Emmanuel Macron had previously dismissed as “brain-dead”, is now getting a new lease of life with the accession of Finland, with once-neutral Sweden next in line to join the alliance.

Switzerland is not considering NATO membership, but wants a rapprochement. Since 1996, under the Partnership for PeaceExternal link, the Alpine country has held the status of NATO partner. This involves military cooperation and sharing of information and experiences. There are no binding legal obligations or automatic mechanisms involved, however – and above all no obligation of collective defence, which NATO membership requires.

More

Swiss defence minister says NATO open to closer ties

With rapprochement, Swiss army participation in NATO exercises and closer collaboration in the area of cyber-security and civil defence are conceivable. The goalExternal link is to work out an Individual Partnership and Cooperation Programme (IPCP) by the summer. The IPCP is a new instrument devised by NATO for cooperation with partner states.

How soon – if at all – this agreement can be achieved is far from clear. Switzerland enjoys no great reputation in the alliance these days. Stoltenberg himself said after his meeting with Amherd in Brussels that “several of the allies have reservations because Switzerland did not agree to them passing ammunition on to Ukraine.” He was referring to the ban, on the grounds of Swiss neutrality, on re-exporting Swiss ammunition that had been sold to various European states years before.

Why put pressure on Switzerland?

That Western powers are putting pressure on Switzerland to reject the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is no great surprise. In the past, other states, including Germany and the then-neutral Sweden, were put under pressure not to sign the text. NATO is raising the price of friendship knowing that it does not depend on Switzerland, but that the opposite is true.

Domestically, however, the pressure is altogether different. The Swiss parliament has debated the merits of joining the TPNW, votedExternal link in favour of signing it, and called upon the government to do just that – but so far without success. The government has put off signing the treaty, citing an ongoing review. A final decision is expected in the coming weeks.

More

Switzerland will remain neutral – until it’s attacked

Will Switzerland sign up to the treaty or not?

If a nation wants to enjoy the protection of a “nuclear alliance”, then it needs to accept its nuclear deterrence capability: so goes the NATO argument. Still, signing up to the TPNW does not seem to be any grounds for exclusion: Austria and New Zealand have ratified the treaty, and are both still NATO partner states.

Swiss politicians and NGOs regularly call on the government to sign the treaty. As the depository state of the Geneva Conventions and with its proud humanitarian tradition, they say, Switzerland can hardly afford not to take a clear position on matters of nuclear disarmament. This year, for the first time, Switzerland is a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. Joining the TPNW would thus have a symbolic effect.

Of course the conflict in Eastern Europe has shaken many certainties. Even inside traditionally NATO-sceptical groups in Switzerland, there is now less opposition to cosying up to the military alliance than in the past. The Russian invasion has led to new geostrategic realities in Europe – though not necessarily of the kind that Russia was expecting.

More

Is Switzerland moving towards a European security alliance?

During the Cold War, plans were afoot in Switzerland to develop the country’s own A-bomb. Fear of a nuclear exchange between the superpowers led to a wish to increase Switzerland’s own military deterrence capability. So the Swiss government stated in 1958External link: “In keeping with our centuries-old tradition of self-defence, this government is of the opinion that the army must have the most effective tools at its disposal to defend our independence and protect our neutrality. The atomic bomb is one of these tools.”

This plan remained a pipe dream due to a lack of nuclear know-how, source of uranium and the financial resources required. In 1969 Switzerland – pressured by the nuclear powers – signed up to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The Swiss atomic bomb project was finally consigned to the bin in 1988.

Edited by Marc Leutenegger, adapted from German by Terence Macnamee/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.