Seven ways the ECHR has shaped Swiss law over the years

For half a century, Switzerland has upheld the fundamental freedoms enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights – except for the rare cases when it hasn’t. We take a look at some of the key moments and court rulings along the way.

In 1974, with Switzerland set to ratify the Convention, Foreign Minister Pierre Graber stuck his neck out. It would be very unlikely that Switzerland, with such high standards, will be taken to task for any violation, he predictedExternal link. For many at the time, the country’s laws were more than good enough to satisfy the Convention and its Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

They were wrong. Since then, while Switzerland has been far from the worst human rights offender in the class, it has been taken to task by the court some 140 times. And over the last half a century, such rulings, as well as the looming influence of the Convention in general, have shaped the country’s judicial system in some key ways.

1971 – better late than never

Compared to its neighbours, Switzerland was somewhat late to the party when it came to ratifying the Convention. Among other things, this was because it was behind the times on another issue: until 1971, Swiss women couldn’t vote at the federal level. Given that human rights famously apply to humans, and not just men, this was a problem. Authorities looked at ways of ratifying the Convention in any case, but couldn’t agree on any; in the end the ECHR was a key factor in spurring Switzerland to finally introduce universal suffrage. In a 1971 ballot, Swiss men accepted the political equality of Swiss women at the national level; three years later, the country signed the Convention.

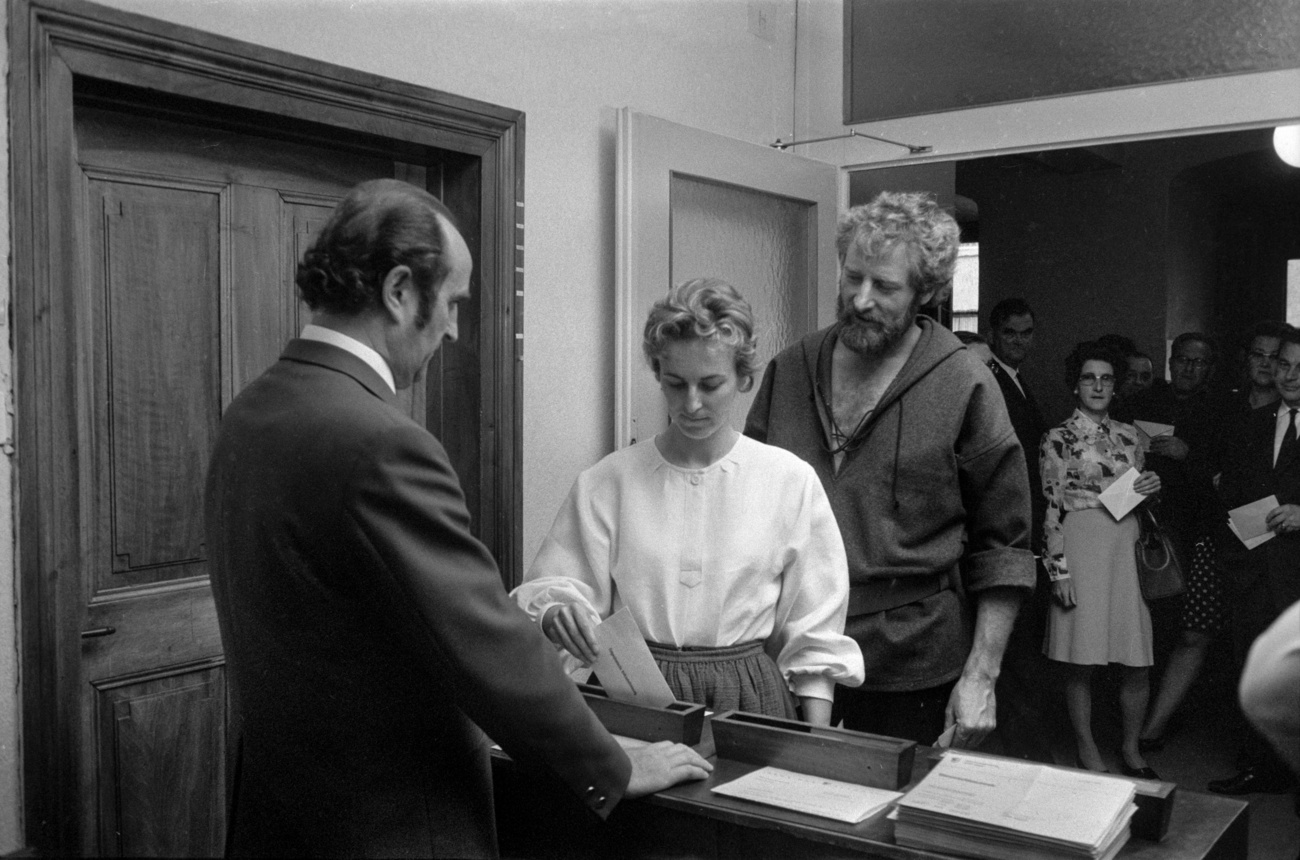

1981 – the end of a dark chapter

The situation was similar for another case of discrimination in Switzerland. For decades, “administrative care” policies had led to the imprisonment of up to 60,000 people without trial and without having committed any crime. The practice targeted people who didn’t meet social standards, for example by their “depraved lifestyle” or “alcoholism”; many were girls who were shunned after getting pregnant. Orphans or illegitimate children were also forcibly placed in foster homes or institutions. Criticism of such practices spread in the 1960s, but it was only after ratifying the Convention in the 1970s – particularly Article 5External link – that politicians took action. Administrative care was officially ended in 1981.

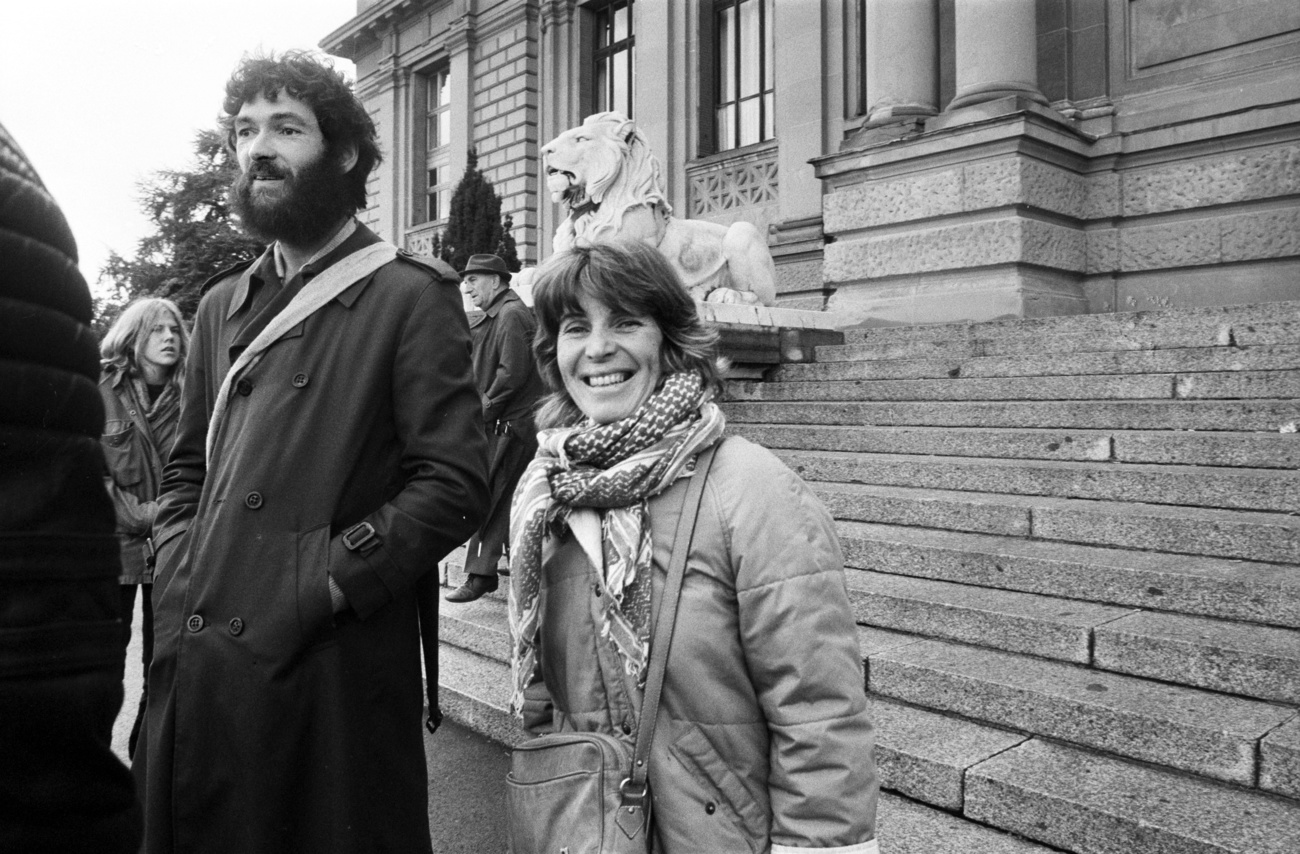

1988 – the right to impartial appeal

In 1981, Lausanne student Marlène Belilos was fined for taking part in an unauthorised demonstration. She contested the charge, claiming she was elsewhere at the time. After a police board rejected her appeal, Swiss courts also turned her down, saying they weren’t able to review the facts of the case, but only whether the law had been applied correctly. Invoking Article 6External link of the Convention, Belilos went to Strasbourg, and in 1988 she won, in a verdict which “sent shockwaves through the Swiss judicial system”, according to Evelyne Schmid from the University of Lausanne. In 2024, if authorities bring a case against you, the right to contest the facts of the case at an independent court seems a no-brainer. In 1988, less so: in the Swiss Senate, it provoked a motion to leave the Convention which was rejected by a single vote.

1992 – in the name of equality

When Susanna Burghartz married Albert Schnyder in Germany in 1984, the couple took her surname as the family name, and they became Susanna Burghartz and Albert Schnyder Burghartz. Under German law, all fine. But in Basel, where they lived, authorities were less excited: they insisted on registering the family name as Schnyder, and forced Albert to drop the Burghartz – only women can have double names, authorities said. Judges in Strasbourg disagreed: there is no reasonable justification for inequality of treatment when it comes to surnames, they ruled in 1992External link. A few decades later, Switzerland still bickers about naming rules.

2011 – the limits of the court, part 1

Despite lists such as this one, success in Strasbourg is rare: the vast majority of cases (94% of those against Switzerland in 2023) are deemed inadmissible or struck out. The court also has a clear mandate, which doesn’t include dealing with abstract challenges against general laws. As such, when some Swiss Muslims appealed a 2009 ban on the building of minarets in Switzerland, they lost out primarily because they failed to prove that their human rights had been directly affected – they couldn’t demonstrate victim status. A ban on minarets may or may not run counter to the freedom of religion (Article 9External link), but it’s only when you’re discriminated against in a concrete way – say, if authorities reject your request to build a mosque with a minaret – that you can appeal to the ECHR.

2014 – the long shadow of asbestos

In 2005, Hans Moor died of lung cancer. The cause of the illness was exposure to asbestos during his working life, some decades previously. Following his death, his wife, Renate Howald Moor, continued court proceedings which Hans had filed after being diagnosed, demanding damages from his former employer, rail manufacturer Alstom. To no avail: Swiss courts ruled that a ten-year statute of limitations applied following the last exposure to the asbestos. In Strasbourg, however, the ECHR judged that such a time limitation clearly infringed the rights of people with diseases that only became diagnosable decades later. In such cases, the statute of limitations must be adapted, the court ruled in 2014External link.

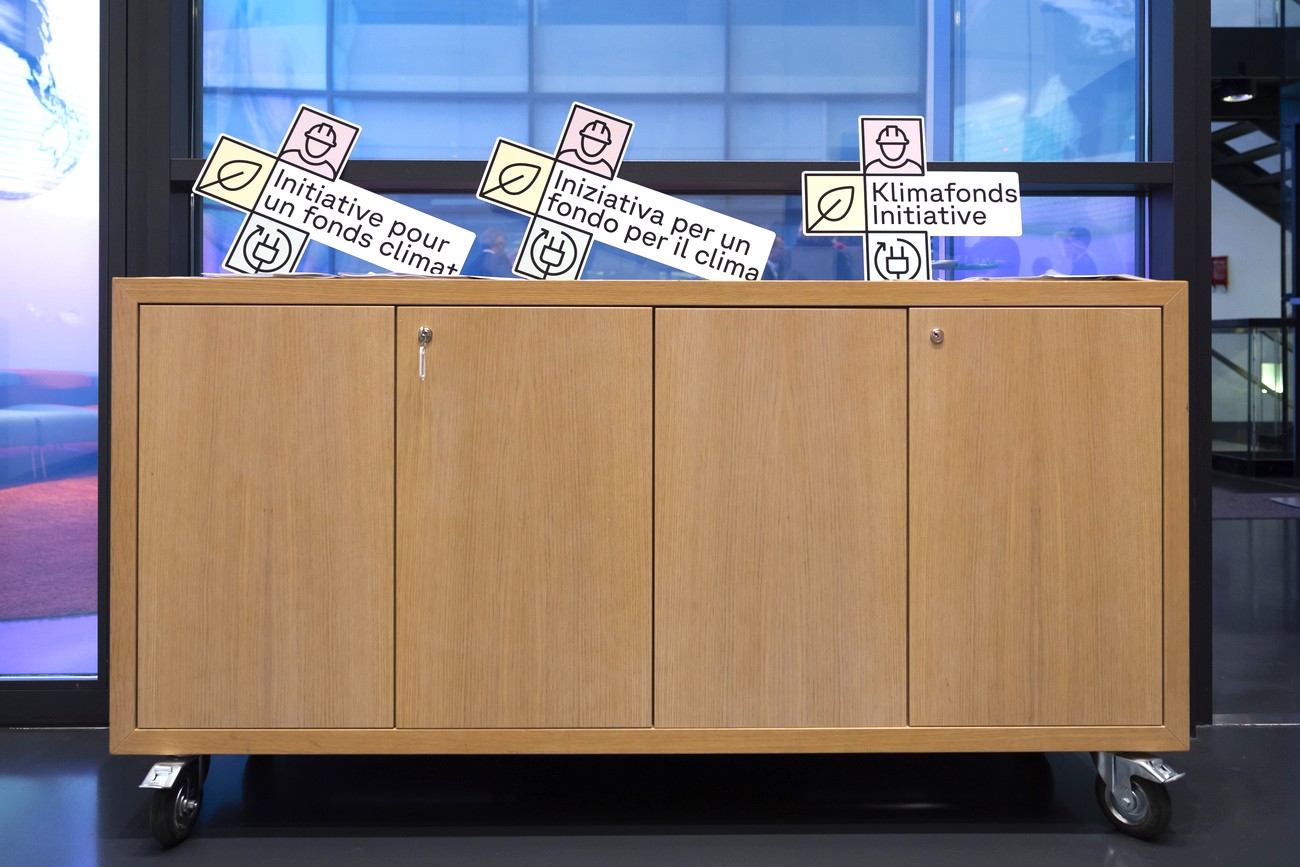

2024 – the limits of the court, part 2

Climate change is another tricky issue when it comes to gauging “direct” impact. The planet is heating up gradually, the causes are diffuse, and the effects are global; in Council of Europe jargon, it is a “transversal themeExternal link”. But in April 2024, after hearing the case brought by a group of Swiss older ladies, the ECHR was clear: the Swiss state was not meeting its international climate obligations and had infringed the rights (Article 8External link) of the women, it ruledExternal link. The verdict made headlines around the world, and sparked hefty pushback in Switzerland, where it revived simmering debates about the extent of the court’s mandate. Even Swiss authorities were unimpressed by the verdict; in 2025, they’ll nevertheless have to show the Council of Europe that they’re implementing it.

The Council of Europe, the Convention and its court

The European Convention on Human Rights, which came into force in 1953, was drafted by the Council of Europe after the latter was founded in the aftermath of the Second World War. The goal of the Convention was and is to protect fundamental rights and political freedoms in Europe – from the prohibition of slavery to the freedom of expression. Ratifying it is a prerequisite for joining the 46-member Council of Europe.

Member states are responsible for upholding the Convention in their national jurisdictions. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), made up of one judge from each member state, hears cases of possible violations. Individuals can bring such cases to Strasbourg after exhausting all legal possibilities at the national level. ECHR decisions are binding, and implementation is overseen by the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers, made up of the foreign ministers of the 46 member states.

Between 1959 and 2021, the ECHR delivered 24,511 judgments. Around 40% concerned just three countries: Turkey, Russia (ejected from the Council of Europe in 2022) and Italy. Judges found violations in 84% of judgments delivered since 1959; at the same time, some 94% of all cases were deemed inadmissible or struck out without judgement. The most common violation (37%) related to Article 6 of the Convention: the right to a fair trial.

Edited by Mark Livingston/ts; image research by Helen James

More

Happy anniversary? Switzerland marks 50 years at the ECHR

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.