Switzerland as a test case for European populism

The ‘rise of populism’ that has caused headaches across Europe recently was experienced much earlier in Switzerland. How did direct democracy help the country absorb such movements, and what’s next?

Political instability in western democracies over the last century has been routinely linked to populism. The search for a “cure” for what the establishment perceives as an abuse of democratic institutions is just as old. Why is the debate so difficult?

One problem is that demagoguery lies in the ear of the beholder. Populism is a tricky term to pin down. Since it can’t really be measured, what we’re often left with is a smorgasbord of definitions, most of them agreeing it amounts to a political style pitting a morally bankrupt “elite” against an oppressed, ignored or defrauded “people”.

As for policies, critics say populists promise overly simplistic solutions for complex problems like immigration, cultural diversity and societal change; populists say the word is a catch-all term used by elites to dismiss arguments they don’t like.

More

Studying democracy in an age of populism

But beyond semantics, the debate matters: IDEA, a Swedish research group, finds that periods in which populists manage to actually get into government are periods of decline on many aspects of democratic health like freedom of expression or civil society engagement.

This is one such period: although “peak populism” may have been reached, according to a European Commission research paper, the overall situation is that such parties have more than tripled their support on the continent over the past two decades.

And, so, even if the thought of governing with groups like the National Rally in France or the Freedom Party in the Netherlands probably sounds frightening to many centrist or moderate folk, there may not be a choice – the alternative is to ostracise growing numbers of citizens.

More

The ‘third wave’ of autocratisation and the dangers to democracy

The Swiss example

As usual when it comes to politics, Switzerland is somewhat unique when it comes to this debate: while the country is often seen as a model of stability and the world champion of (direct) democracy, it’s also highly populist, and has been for some time.

More

Switzerland ranked highly for ‘authoritarian populism’

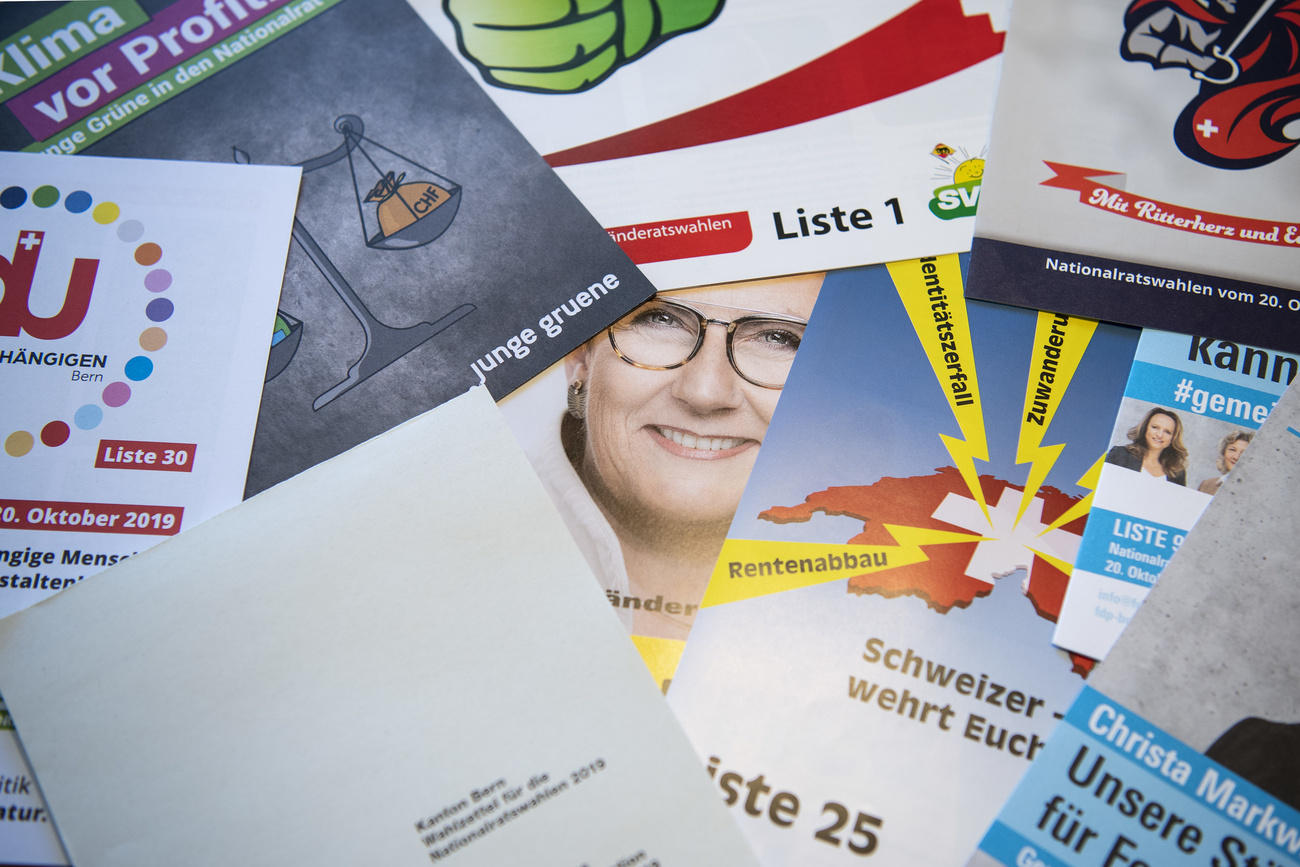

The past three decades have seen a sharp rise in the success of populist movements in the country, mainly the right-wing People’s Party, whose parliamentary strength grew from 12% in 1991 to a peak of 29.4% in 2015.

Despite the big gains in last year’s elections made by the Greens – who have themselves been labelled populist in the past –, the People’s Party remains the strongest group in parliament in 2020.

How has the country managed to avoid the political instability and inflamed rhetoric that’s associated with populist groups in other western countries? Direct democracy might play a role, experts say.

More

In Switzerland, populism thrives – but under control

On one hand, direct democracy actually encourages populism by allowing ideas onto the agenda that would be blocked under a different system. Citizens can propose legislation and vote up to four times a year on initiatives, and can thus bypass the vested interest of elites.

But direct democracy also tempers populism for the same reason, by constantly asking for citizens’ input in the political process. Swiss voters, used to regular ballots and deliberation, have lots of chances to make their voices heard: and so, issues “rise to the surface faster, more clearly, and must be solved”, as analyst Claude Longchamp puts it.

Elsewhere, problems might go unaddressed and fester below the surface, says Ralf Schuler, a German author. “[Populist] movements take up issues left untackled by established parties, and “attract people from the margins susceptible to their arguments”, he says.

Lastly, of course, there is the ‘magic formula’, which means that the Swiss government is always made up of a consensual, representative roundtable from the biggest parties in the country – regardless of what they stand for.

More

What do Swiss political parties stand for?

And so, while populist groups elsewhere are vilified or ostracized, in Switzerland, the People’s Party is a long-standing, legitimate participant in government, where it works pragmatically with the others – rather than fuming from beyond a sanitary cordon.

As for the future of populism, author Roger de Weck reckons Switzerland could again show the way: “my hope is that Switzerland, which was the first European country to experience reactionary populism, will be one of the first to reject it,” he told swissinfo.ch.

More

The political equation based on a magic formula

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative