How the United States used humanitarian aid for influence

By dismantling USAID, US President Donald Trump is turning his back on a century-old strategy of using humanitarian aid as a tool of influence in the world. But by weakening this pillar of US diplomacy, Washington risks running counter to its own interests.

The new Trump administration’s dismantling of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) at the start of the year has highlighted the humanitarian sector’s dependence on American funding.

All of a sudden, the programmes of multiple humanitarian actors all over the world – UN agencies, international and national NGOs, local governments – were plunged into profound uncertainty.

This article is the last in a three-part series looking at the future of humanitarian aid, as the US and major Western donors disengage from the field. The first part explores the impact of budget cuts on humanitarian agencies’ work on the ground. The second part examines the chances of emerging countries, and even private players, filling the funding gap.

In Sudan, which is in the grip of one of the world’s worst crises, more than half a million people risk losing regular access to food, while in Yemen some 220,000 displaced people may no longer have access to healthcare.

Before the cuts, which are still hard to estimate in terms of scale, the US alone funded 40% of global humanitarian aid. This is far more than the 8% funded by the second-largest contributor, Germany.

“This percentage reflects the place of the United States in the geopolitics of the 20th century,” says Valérie Gorin, head of learning at the Geneva Centre of Humanitarian Studies.

Herbert Hoover, father of food aid

To understand the origins of this influence, one has to go back to the First World War, in 1914.

With Belgium occupied by the Germans and suffering a terrible famine, the United States set up an aid committee to distribute food parcels to the Belgian population. It was headed by Herbert Hoover, who later became president.

After the First World War, in 1919, Hoover created the American Relief Administration (ARA), predecessor of USAID. This food aid organisation originally distributed surplus rations that the US army had not given its soldiers during the war.

In 1921, the ARA intervened in Soviet Russia, which was facing a major famine. “The question was whether to help people in Communist-controlled regions,” says Gorin, “and especially how to use this food aid as a tool against communism.”

The US also provided wheat, which it produced in excess, and agricultural machinery. Its aim was to present itself as an altruistic country, demonstrate the superiority of the capitalist model, and stimulate the American economy, according to Bertrand Taithe, director of the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute at the University of Manchester.

Tool against communism

“The Americans use humanitarian aid to win hearts and minds,” Gorin says. “It’s not a disinterested act of solidarity but a tool of American diplomacy.”

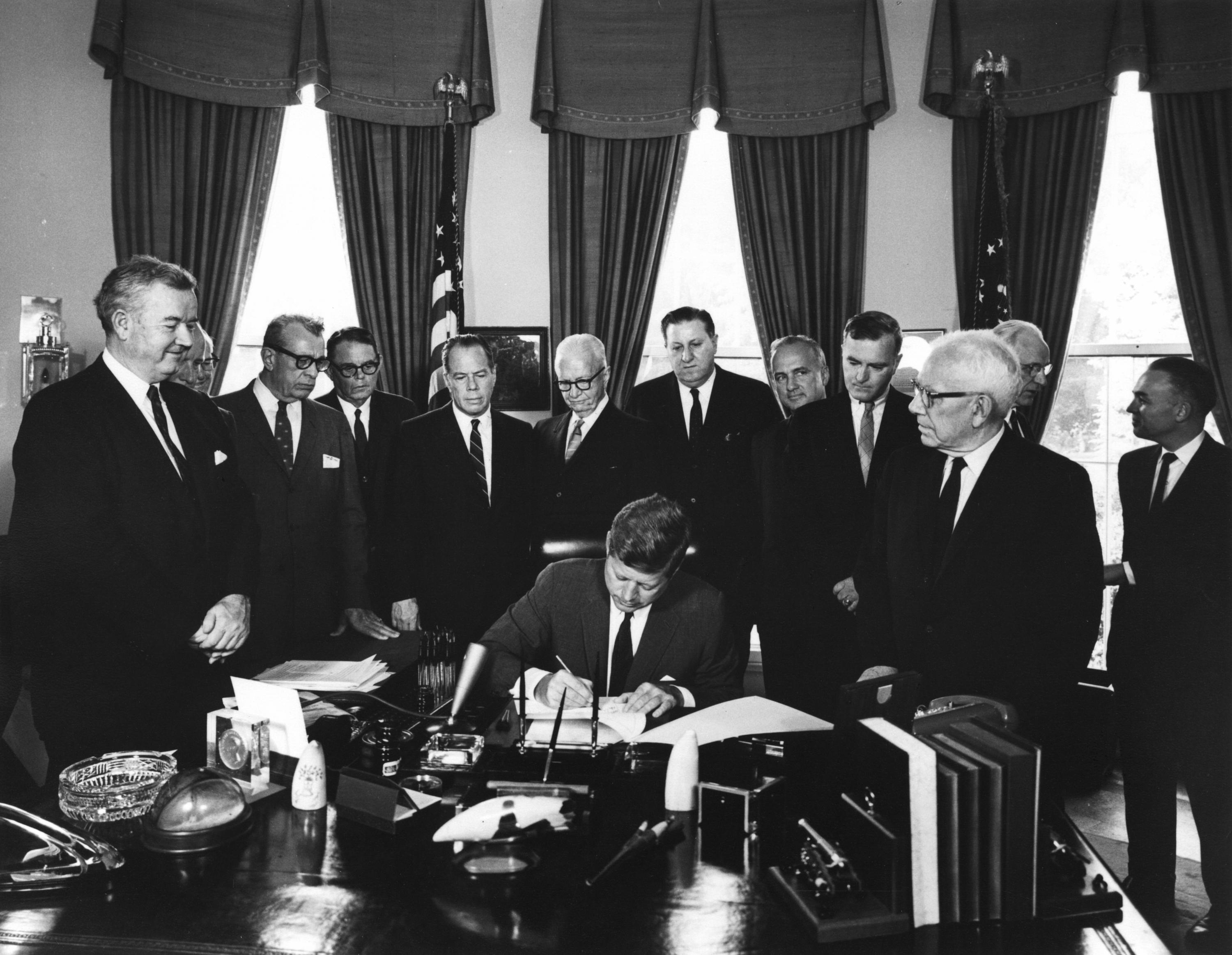

This was clearly stated during the Cold War, which divided the world in the post-war period. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy set up USAID. “As we do not want to send American troops to a great many areas where freedom may be under attack, we send you,” he told his recruits, as reported by the Financial TimesExternal link.

The idea was simple, Gorin says: poverty was the breeding ground for communism – and that’s where the United States decided to act.

“Food aid was intended to help win influence in places where communism was gaining ground, and in regions that needed stabilising to act as a buffer between the Eastern and Western blocs,” she says. These included especially the newly decolonised countries in Asia and Africa.

More

Birth of the big NGOs

The Cold War was a period when big American international NGOs such as CARE, Save the Children and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) flourished. They received substantial state funding, which sometimes went along with close links to the government.

“There was a kind of alignment between the NGOs’ objectives and those of US foreign policy,” Taithe explains. This alignment stemmed from the organisations’ financial dependence on government, and also the fact that “many people were fleeing totalitarianism, so there was a rapprochement between the promoters of freedom, those who sought freedom, and those who helped these people”, he adds.

Shared aims were apparent during the Vietnam War, between 1955 and 1975. Most American NGOs intervened only in South Vietnam, which got US military and economic support, and not in North Vietnam, which was controlled by a communist regime. But as the conflict dragged on, some humanitarians started questioning this.

“The more pacifist organisations, which approved neither the objectives nor the methods of this war, distanced themselves from the American state,” Taithe says. This was the case, for example, with CARE and Oxfam America, which started reconsidering their partnership with USAID.

‘Humanitarian military intervention’

US military interventions in the decades that followed, in Afghanistan and Iraq for example, were accompanied by humanitarian aid, particularly food and medical aid. The aim was to stabilise the occupied zones and increase the legitimacy of the US-backed authorities.

“We talk about humanitarian military intervention, with a confusion of terms,” Gorin says. “Humanitarian aid becomes a way of imposing democratic aspirations on certain countries.”

In 2001, as the invasion of Afghanistan started, US Secretary of State Colin Powell explicitly stated that NGOs were a key element of American military efforts. In a speech, he described them as “force multipliers” and “an important part of our combat team”.

This rhetoric – contrary to the principles of neutrality and independence – was strongly criticised by humanitarian NGOs. MSF said such words endangered its staff and hindered its access to civilian populations. During this period, NGOs were the target of several terrorist attacks, the most well-known being the explosion of a truck bomb outside the UN office in Baghdad in 2003.

“NGOs sought to protect their independence but did not always hold out when promised US government funding,” Taithe explains. “The United States has always used humanitarian aid to make new friends, maintain existing ties and increase its influence.”

Loss of influence

In some areas, notably health, American aid has been widely acclaimed, giving the country a global profile. For example, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), set up by President George W. Bush in 2003, has saved millions of lives, particularly in Africa. Its future is now under threat, as is that of many programmes previously funded by USAID.

+ To find out more about the impact the US cuts are having, particularly on women and HIV programmes, listen to the latest episode of our Inside Geneva podcast.

As part of his “Make America Great Again” programme, Trump has portrayed foreign aid as ineffective, too expensive and controlled by the political left. While his assault on USAID was anticipated, the speed and scale of the cuts came as a surprise. Trump claims he is focusing on direct US interests, but Taithe thinks dismantling USAID is above all an “ideological decision”.

“It will have a negative impact on American interests,” he says. “Both domestically – because much of the aid is indirect support for agriculture – and externally, because it is a clear loss of influence in the world.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin/sj. Adapted from French by Julia Crawford/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.