Appenzell Inner Rhodes: the last Swiss canton to give women the vote in 1991

While Swiss women were allowed to vote at a national level in 1971, those of canton Appenzell Inner Rhodes had to wait until 1990 and a ruling of the Federal Court to do so at a cantonal level. Some of the Appenzell women talk to SWI swissinfo.ch about living in the canton and remember casting their first vote.

Maria Vitti holds no grudges against the men in her canton who denied her the right to vote until 1990. “They did not act to spite women,” she said while straightening a client’s hair.

“They wanted to hold onto their traditions which are very strong in Appenzell Inner Rhodes.”

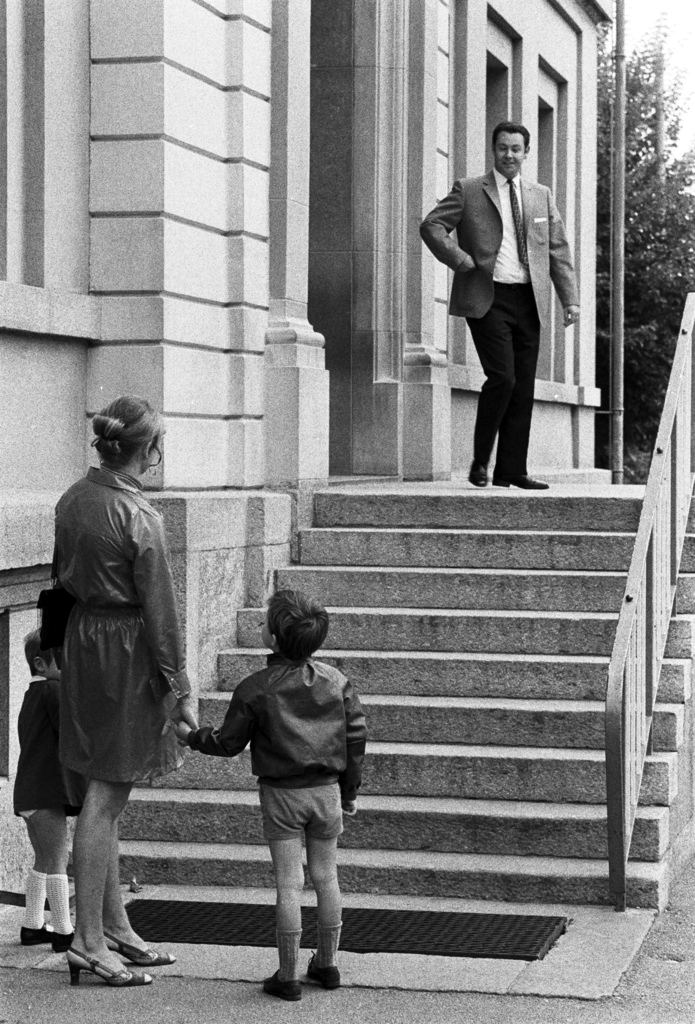

Vitti, who runs a hair salon in the village of Appenzell, the capital of the canton, recalls family discussions around how the men in the village would vote, but at the end of the day, only the man of the house would be allowed to go out and cast his ballot.

“Casting a ballot is a fundamental right and apart from tradition, there is no valid argument why women should be denied it,” she said in hindsight.

Women in Appenzell Inner Rhodes, the smallest canton in Switzerland, were only granted political rights 30 years ago, far later than the other Swiss cantons. Though many local women in the canton, worked in the embroidery business making them the main breadwinners of the family, the political sphere remained a man’s world late into the twentieth century.

More

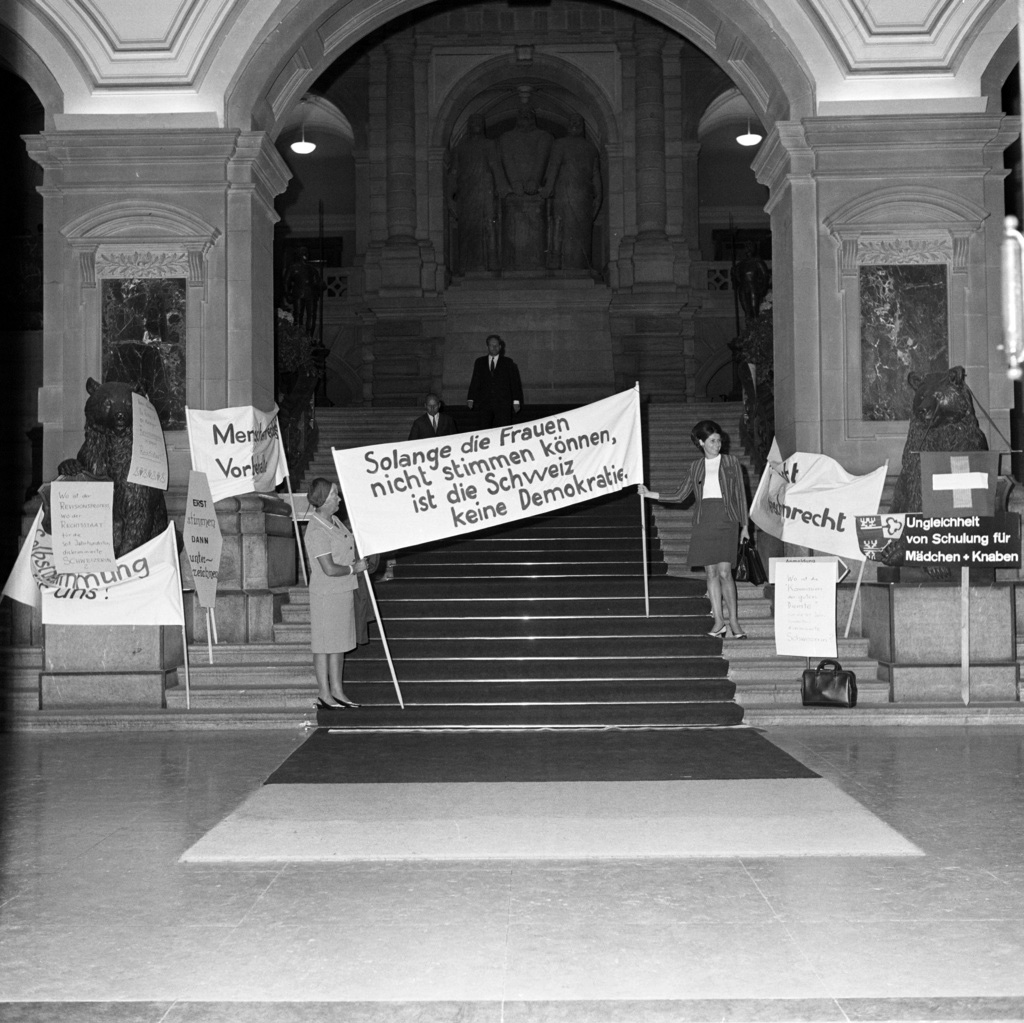

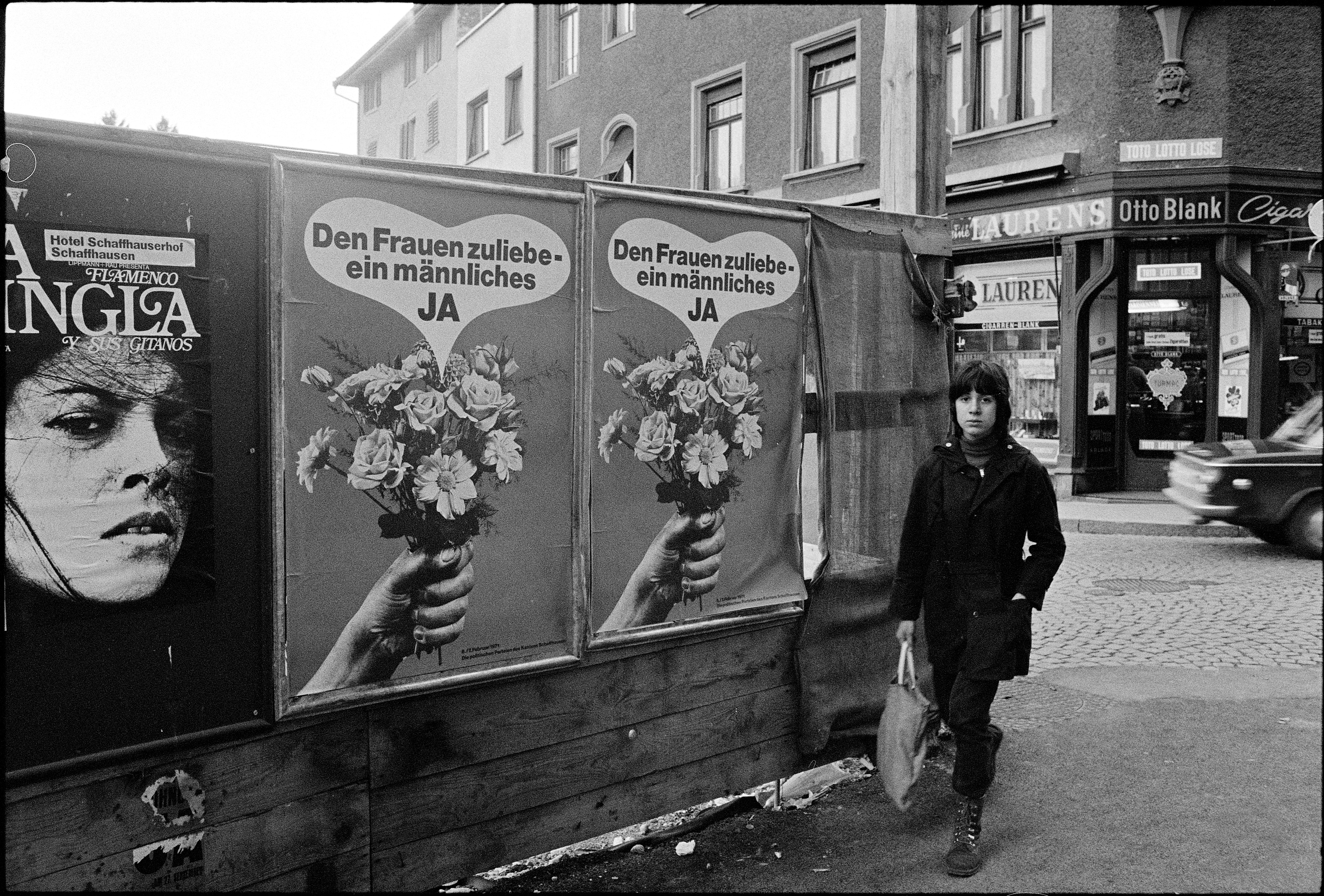

National voting rights for women in Switzerland were introduced in 1971, 65 years after Finland, the first country in Europe to do so, and 12 years after the men of canton Vaud were the first in Switzerland to vote in favour of women’s suffrage – for cantonal decisions.

Almost all cantons followed suit in 1972. Two cantons resisted. In Appenzell Inner Rhodes and Appenzell Outer Rhodes women could vote on national matters – but the cantons refused to let them have a say at a local level. The women of Appenzell Outer Rhodes had to wait until 1989 to cast their first cantonal ballots after the men of the canton finally agreed to let them vote. In Appenzell Inner Rhodes the right had to be imposed by the Federal Court – against the decision of the male voters and after a petition was filed by some of the local women.

More

The introduction of women’s suffrage worldwide

‘The village‘

In Appenzell Inner Rhodes, voting happens once a year in the town square which turns into a Landsgemeinde – an open-air assembly where citizens vote on cantonal matters with a show of hands.

On February 7, 1971, women finally gained the right to vote in national elections. Switzerland was one of the last countries to introduce universal suffrage. This makes it a young liberal democracy even though it is widely viewed as a model of direct democracy.

SWI swissinfo.ch devotes a special feature to this inglorious anniversary. This first report is about Appenzell Inner Rhodes which became the last Swiss canton to introduce women’s suffrage at cantonal and communal level in 1991.

On March 4, 2021, SWI swissinfo.ch will conduct a digital panel discussion on “50 years of women’s suffrage: old question of power, new struggle with new minds”.

Anju Rupal, a Briton of Indian descent who gained Swiss citizenship through marriage, was part of the first women to ever enter the square and participate in the Landsgemeinde. Simply talking about the historic day still fills her with joy.

“I was so excited that I raised both hands. I guess mine were the only dark hands going up in the air that day,” she recalled.

Rupal, has lived in “the village”, the capital of Appenzell Inner Rhodes, since the late 1980s. When she first arrived, she had no idea that women were not allowed to vote. “My girlfriends sent me clippings from the The New York Times and The Guardian about it,” she remembered. Rupal assumed that women’s suffrage prevailed in all western democracies.

“In Appenzell, people ask: ‘Who do you belong to?’,” she explained, adding that attitudes like this are part of the reason why women have been excluded from gaining political rights for so long.

A piece of Walt Disney

Whilst feminist movements demanding more rights for women, formed through Switzerland, after the 70s, Appenzell Inner Rhodes, remained secluded. On Swiss television, feminists from the big cities called the canton ‘piece of Walt Disney’ and said they needed their own feminist movement. But when the national social democratic women’s organisation held its annual meeting in Appenzell at the end of the 1980s, it was met with strong resistance.

“(At the time) there were individual activists like Ottilia Paky-Sutter and artist Sibylle Neff, who threw plates out of the window in protest during the Landsgemeinde,” art historian Agathe Nisple remembered. The boldest move, she said, was an advertisement where the women of Inner Rhodes publicly declared their support for universal suffrage.

Nisple, who is now 65 years old, was born and raised in Appenzell Inner Rhodes but ventured outside the cantonal borders to study and work. She belongs to the first generation of Swiss women who were allowed to vote and get elected at a national level. However, in her home canton, she was unable to participate in political life until 1991. “It has already been 30 years, or shall I say ‘only’ 30 years?” Nisple said, as she throws her hands up in disbelief.

After Appenzell Inner Rhodes’ all-male Landsgemeinde rejected the introduction of women voting rights for the third time in spring 1990, 100 signatures were collected, and a legal action was brought before the Federal Court in Lausanne. On November 26, 1990, the court agreed to overrule the canton.

“I was very grateful for the Federal Court’s decision,” Nisple said. “Without this move, women might still not have the right to vote in our canton.”

Opponents against granting women’s rights argued among other things the square was too small to include women. In a televised discussion one adversary claimed that the Landsgemeinde was for men what Mother’s Day was for women.

Agathe Nisple has always been open about her support for women’s voting rights. “I remember my colleagues teasing us at our regular meetings down at the pub when I was young. They said women’s suffrage was unnecessary,” she remembered. “I have always met provocation with constructive explanations, but now I wonder whether this was the right thing to do?”.

At the beginning of the 19th century, eight Swiss cantons held open-air voting assemblies. The mountain region of Glarus and the rural canton Appenzell Inner Rhodes are the only two cantons that still follow this tradition. In neighbouring Appenzell Outer Rhodes, men voted in favour of female suffrage in 1989. This decision dented the confidence in the archetype of direct democracy among many male supporters and opponents of women’s rights to such an extent that a majority voted for the abolition of this form of voting.

One Landsgemeinde for both sexes

The premiere of women entering ‘the ring’ of the Landsgemeinde went smoothly, according to Nisple. “I was very surprised, but happy at the same time”. About a third of the 4,000 participants in the 1991 vote were women. But only one woman dared speak up. “Once you have a voice, you are exposed,” according to Nisple. “It’s exhausting to have a different opinion, but that’s part of the game.” Any argument on the podium can change the atmosphere and that’s why Nisple enjoys this democratic tradition to this day.

People in the rest of Switzerland deem the Landsgemeinde as pre-modern. The assembly is tied to a certain place and time; those who are sick or out of town are excluded from the vote, while everyone can see what people vote for. Voting secrecy is considered a precondition for a well-working democracy.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the women of Appenzell Inner Rhodes became more active and founded their first women’s association. Local women became judges and grand councilors. Ruth Metzler, one of the most famous women from the canton, become a Federal Councilor. But compared with the rest of Switzerland, women are still seriously underrepresented in the cantonal government where only 11 of the 50 members are women.

Gerlinde Neff-Stäbler is a female member of the cantonal government. She remembers how she experienced the first voting event in the main square 30 years ago. “It was a Wednesday, and the old town was filled with smoke. Farmers, cattle farmers, millers and flour traders were sitting around smoking their pipes and cigarillos.”

“There were no women. I had just moved here from Stuttgart and was wondering what this male crowd was all about.” Neff-Stäbler initially came to eastern Switzerland to work as a nurse, but soon gave her job up to help her husband, originally from Appenzell, manage his dairy farm.

Today she represents the farmers’ faction in the local parliament. “I am a reasonably calm person and not a vehement fighter,” she said. Compared to the debates in the national parliament, Neff-Stäbler says she is glad that the tone of voice in her local parliament is a lot friendlier. “ However, we also need women to get loud to push through their demands,” she said.

“We can only hope that in the end we will have equal rights.”

Just recently, a local man told her that he had not attended a Landsgemeinde since the introduction of voting rights for women. “Some men still refuse to accept it, while some women refuse to attend,” concluded Neff-Stäbler.

Ottilia Paky-Sutter, from Appenzell, is a pioneer for women’s rights who lost her Swiss passport when she married an Austrian in 1947. The exclusion pushed the original Appenzeller and folk music star to become increasingly politicised. The Appenzell Landsgemeinde voted in favour of reinstating Swiss citizenship to her and her family in 1952 for the sum of CHF 2,500, which equals about CHF 12,000 in today’s value. The experience left her wounded for the rest of her life and turned her into a feisty advocate for women’s voting rights. At the end of the 1970s, Paky organised women’s assemblies that were attended by some 60 women.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.