Geneva platform helps climate refugees around the world

Climate refugees have grabbed international headlines and their stories resonate easily, mirroring those of conflict refugees. Yet the topic is extremely complex, say experts. The Geneva-based Platform on Disaster Displacement is one of the organisations working on this issue, seen as one of the biggest humanitarian challenges this century.

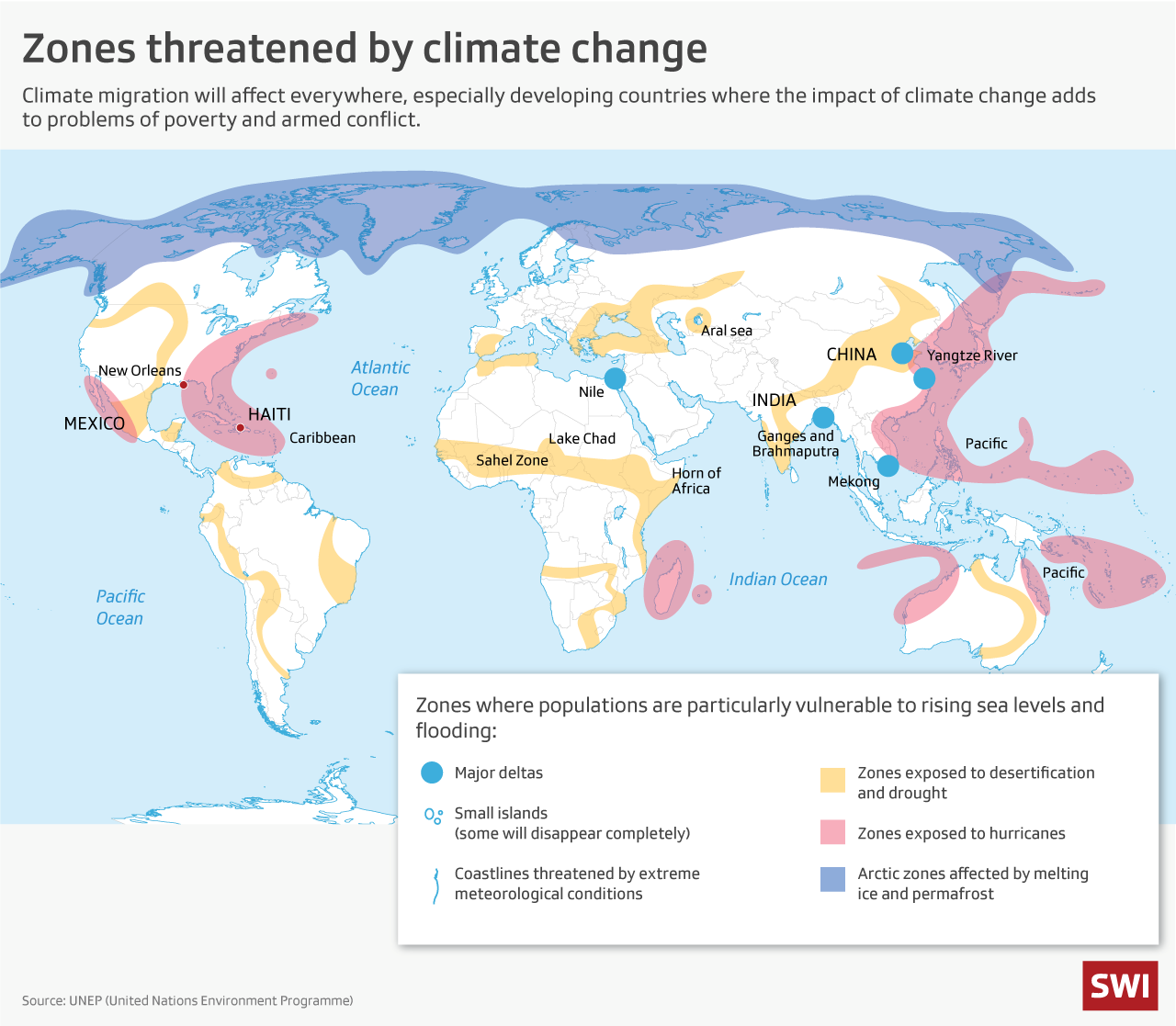

According to the Geneva-based Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCCExternal link), it is estimated that sea level rise associated with a 2°C warmer world could submerge the homeland of 280 million people by the end of this century.

Currently, many countries and regions are affected by disasters year after year. In 2018 alone, 17.2 million peopleExternal link were forced to leave their homes due to disasters in 148 countries and territories and 764,000 people in Somalia, Afghanistan and several other countries were displaced following droughtExternal link.

“We have a good general understanding of the scale of problem in terms of the numbers of people being forced to leave their homes because of sudden disaster events. But we don’t know how many of these people actually then cross borders,” explains Walter Kälin, envoy of the chairmanship of the Geneva-based Platform on Disaster DisplacementExternal link, the follow-up to the Nansen Initiative.External link

That intergovernmental process, launched in 2012 by Switzerland and Norway, aimed to provide states with a “toolbox” on how to prepare for forced migration due to severe climate change effects.

Climate refugees – like the case of Ioane Teitiota from the Pacific island of Kiribati decided in a recent landmark UN Human Rights Committee rulingExternal link (see infoboxes below) – have grabbed international headlines and their stories resonate easily, mirroring that of conflict refugees.

Yet the topic is extremely complex, say experts. The convention relating to the status of refugees, signed in 1951, has no provision for climate change as a reason for people to flee their country and seek asylum elsewhere. Climate migration is mostly internal. It is not necessarily forced, and isolating environmental or climatic factors is difficult.

“Disaster displacement is really a cross-cutting issue,” explains Kälin. “It has to do with climate change, disasters, migration, humanitarian action and development aid… and in most cases, displacement is multi-causal.”

Multiple actors

Launched in May 2016, the Platform on Disaster DisplacementExternal link is just one international initiative trying to help such vulnerable people. The state-led project (19 countries, including Switzerland) aims to provide “greater protection to people displaced across borders in the context of disasters and the adverse effects of climate change”.

Other Geneva-based organisations are very active in this area, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which has created an environmental migration portalExternal link, and the UN Agency for Refugees (UNHCRExternal link). Following the Paris climate talks in 2015, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) also set up a special taskforce on displacementExternal link. Meanwhile, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMCExternal link) is a leading international body monitoring conflict- and disaster-related internal displacement worldwide.

Compared to 2012, when the Nansen Initiative was launched, there is now much greater interest and widespread recognition of disaster displacement as a protection challenge in the international community, said Kälin.

He points to the inclusion of disaster displacement in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk ReductionExternal link and in objectives of the Global Compact on MigrationExternal link.

More

Putting climate refugees on the international agenda

For the moment, this increased focus and the multiplication of initiatives and actors hasn’t really lead to any doubling up or competition, said Etienne Piguet, a professor at the University of Neuchâtel and migration policy expertExternal link.

“The people involved in the different initiatives know each other and share information. In the long term we hope there will be more clarity about who is doing what, but the increase in the number of actors is positive,” he said.

Kälin agreed: “It’s not perfect. I mean, the silos are silos. You know how hard it is to overcome and link silos. But I think we are on the right track at a very abstract level. The big challenge is to translate all this abstract work into realities.”

Unlike IOM or the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), the Platform is not an operational organisation, but focuses on political advocacy, he explained.

Its current strategy also involves helping states exchange best practices to better deal with people displaced across borders by disasters and strengthening national and regional capacities. Regional programmes have been introduced in Central America, South America and Fiji, for example, and it is working with the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an eight-country bloc in east Africa.

“It might seem like nothing is produced but we need this kind of institution to allow dialogue between partners,” said Piguet.

More

How climate change affects migration

Swiss policy

Switzerland is concerned by the issue of people displaced by disaster and climate change. After helping co-launch the Nansen Initiative, Switzerland remains an active member of the Platform’s Steering Group. Since 2016, it has donated CHF1.1 million a year to the organisation, which employs six staff.

In the same field, the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs also funds the Washington-based Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)External link and has a strategic partnership with IGAD aimed at improving the management of migrants and refugees affected by natural disasters and climate change in the Horn of Africa.

Piguet said Switzerland was very involved with numerous organisations in this field, including IOM and UNHCR.

But he was critical that Switzerland had ratified the Global Compact on RefugeesExternal link but had not adopted the parallel Global Compact for Migration, which it helped shape and which has a disaster displacement focus.

“It’s damaging for Switzerland as it wasn’t totally understood by a whole series of partners,” said Piguet. “It was very badly launched and is regrettable. But I think we can still correct things.”

Ioane Teitiota case

On January 21, the UN Human Rights Committee published a non-binding ruling for Ioane TeitiotaExternal link, from the Pacific nation of Kiribati, who brought a case against New Zealand in 2016 after authorities denied his claim of asylum as a climate refugee.

Teitiota migrated to New Zealand in 2007 and applied for refugee status after his visa expired in 2010. He claimed the effects of climate change and a rising sea level had forced him to migrate. He was deported to Kiribati in September 2015.

The committee upheld New Zealand’s decision to deport Teitiota, saying in his case he did not face an immediate risk if returned, but it agreed that environmental degradation and climate change are some of the most pressing threats to the right to life.

“Without robust national and international efforts, the effects of climate change in receiving states may expose individuals to a violation of their rights,” the committee said. This would trigger non-refoulement obligations which forbid a country form returning asylum seekers to a country in which they would likely be in danger.

Consequences of UN ruling

The January 21 UN Human Rights Committee asylum ruling (see infobox above) centres on the case of Ioane Teitiota, whose home – the Pacific Island of Kiribati – is threatened by rising sea levels.

Kälin said the UN panel’s decision was historic but its immediate effect was “very limited”: “It doesn’t create a refugee status. It doesn’t mean that we now have a lot of people who fulfil the conditions set by the committee. They are rather strict.”

Piguet: “I don’t think we’ll have more climate refugees after this decision. It’s a symbolic decision. It shows the level of awareness and that in certain regions there is a risk of displacement and that in some countries the non-refoulement of these people is becoming an issue.”

In the past the Swiss governmentExternal link has said existing asylum law and provisional admission would cover any asylum seekers displaced for environmental reasons. Anja Klug, head of the UNHCR office for Switzerland and Liechtenstein: “I don’t expect asylum claims in Switzerland purely based on climate change, but there are claims where climate change is a factor.”

Kate Schuetze, Pacific Researcher at Amnesty International: “The decision sets a global precedent… the message is clear: Pacific Island states do not need to be under water before triggering human rights obligations to protect the right to life.”

More

Why do we need the Global Compact for Migration?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.