Which heroes should we cast in bronze?

Statues celebrating dead generals and philosophers are found in city squares around the world. But what about contemporary heroes? In Geneva, memorials to Edward Snowden, Nelson Mandela and the Armenian genocide have put the spotlight on the role of public art.

“A lot of people say they are traitors, but I want to celebrate these living heroes …my work is a monument to the future,” declared Italian artist Davide Dormino outside the United Nations headquarters in Geneva recently.

Behind him stood his life-size sculptures of whistle-blowers Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning, which he had installed for a week on Geneva’s Place des Nations on a tour of Europe.

A local association that helped Dormino organise the Geneva stop-off would like the sculpture to become a permanent fixture in the city. But it is likely to have a tough time getting approval from local officials like Geneva President François Longchamp, who oversees public art questions.

“Geneva has a tradition of never paying homage to anyone living,” Longchamp told swissinfo.ch. “We never give the names of streets to people until they have been dead for at least ten years and we only create monuments to exceptional people.”

On September 17, the same week as the whistle-blowers were unveiled, a dead hero was celebrated at the nearby Rigot Park. Around 100 people inaugurated a memorial to Nelson Mandela, entitled “Hating only harms the hater” by Léonard de Muralt, a student at the Geneva school of art and design (HEAD).

“The 4m2 [stone area] is the space in which Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for many years,” explained de Muralt, adding that the white rocks symbolised the quarry where Mandela was forced to do hard labour. The 12 metal masts are supposed to evoke the flagpoles of nations and the bars of a cell.

“They symbolise escape and spiritual transformation,” said de Muralt, who urged officials to remain vigilant and “critical of today’s apartheids”.

“Is that possible with art?” an editorial in Le Matin newspaper asked sarcastically. It questioned whether a human statue of Mandela would not have been “more explicit and attracted tourists” like the nearby Mahatma Gandhi bronze.

De Muralt said he had expected criticism: “Some might not like the minimalist or abstract concept and want a head or icon – that’s normal. The idea of art is to create a debate with society. But there are risks, as we saw with Anish Kapoor in Versailles.”

At the end of September, it was reported that a sculpture by artist Anish Kapoor in the Versailles Palace gardens would be covered with gold leaf to mask anti-Semitic graffiti that had caused an outcry in France. The controversial red trumpet-shaped work by the British-Indian Jewish sculptor was dubbed the “Queen’s Vagina” by media and has been vandalised several times since its installation in June.

The same fate is unlikely to befall the young Swiss. Yet there are risks putting work in the public space, say art experts.

“It’s a genre that is full of codes and constraints and ideological background, which creates difficulties for artists who are responsible for not only implementing the project but also overseeing questions like public safety and durability,” explained HEAD director Jean-Pierre Greff.

But it’s a challenge artists are really looking for, especially in a highly politicised place like Geneva, he added.

Longchamp said many artists were looking to profit from the “Geneva brand”, recalling the case of Zurich sculptor Vincent Kesselring who tried to install a seven-tonne sculpture entitled “Bisou” permanently by the lake. After a three-year legal battle, in June 1998 residents were asked to decide; 65% roundly rejected the project in a local vote.

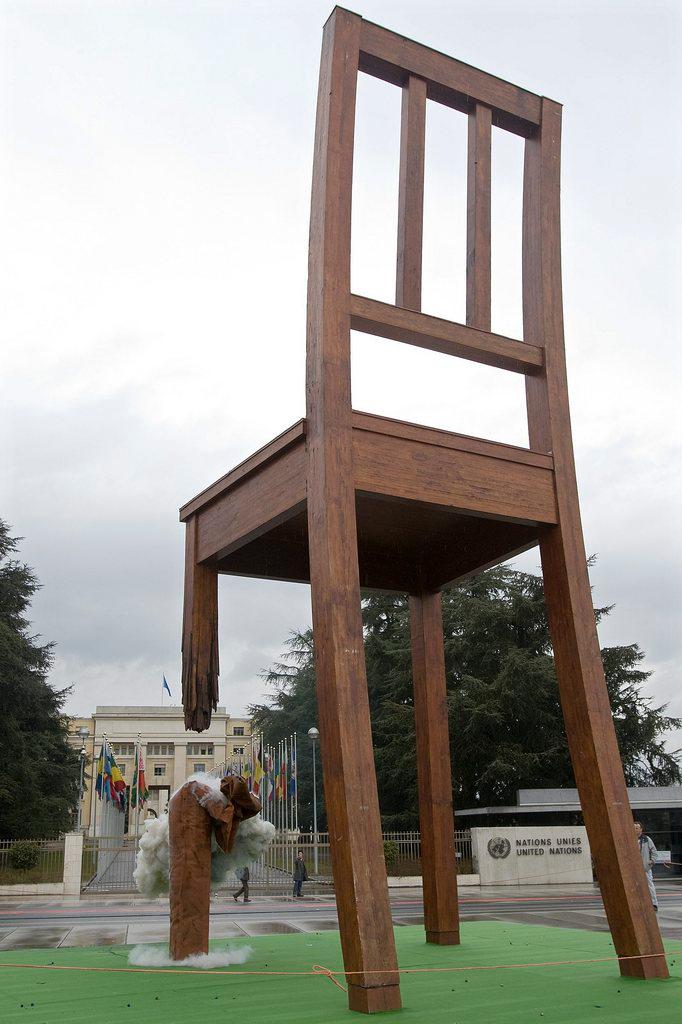

Another temporary work was more successful in gaining legendary status. The Broken Chair, a 12-metre-high wooden sculpture by Swiss artist Daniel Berset, is a permanent tourist attraction on the Place des Nations. It can even be seen on the Geneva version of the Monopoly board game.

But it wasn’t always that popular, explained Jean-Baptiste Richardier, one of the founders of Handicap International which erected the chair temporarily in August 1997. Initially, it was to remain for three months until the signing of the Ottawa Mine Ban in December 1997. But public support meant it was left in place until 2005, before being removed to allow for extensive changes to the square.

The return of the sculpture was delayed and called into question, however. The chair had become a “troubling” symbol for the UN and states that had not ratified the mine treaty, explained Richardier: “There was also a misunderstanding that it somehow represented the unbalanced state of the UN.”

After a behind-the-scenes fight, eventually Geneva officials and former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan held sway over the critics and the chair was reinstalled in the same place in February 2007.

A new era means a new memorial saga in Geneva. This time it is the “Streetlights of Memory” by French-born artist Melik Ohanian, a tribute to the victims of the Armenian genocide and a symbol of a century of Swiss solidarity for them.

Ten years after its creation, the controversial project is still in search of a location in Geneva. In December last year the Swiss foreign ministry expressed concerns at it being installed in the Ariana Park close to the UN headquarters where it could affect the “peaceful and impartial environment”. After years of to-ing and fro-ing, a resolution could be in sight.

“Things are progressing,” said Rémy Pagani, who heads the city’s construction and urban development department. “We have found a place. But I can’t say where. The work is currently in Venice and we hope to install it here in Geneva. It was blocked; there has been a lot of pressure.”

Public space is full of symbolism and requires great care, said the former mayor.

“When you interfere in the public space, you intervene somewhere that concerns all of us. It’s a place of freedom and each and every intervention needs to be carefully thought through with great intelligence,” he added.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.