So many war crimes, so little justice

The United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism has announced its final conclusions on April’s chemical attack on the Syrian town of Khan Sheikhoun, in which at least 80 people died.

The chemical used was the nerve agent Sarin, the UN investigators said on October 27, adding that they were “confident the Syrian Arab Republic [was] responsible”.

The conclusions did not come as a surprise. Initial investigations by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical WeaponsExternal link and the UN’s Commission of Inquiry on Syria had already yielded strong evidence about what happened in Khan Sheikhoun.

But while the circumstances of the attack now seem clear, there is no real answer as to what to do about it. Chemical weapons are prohibited under international law; using them is a war crime. But no one has been charged, no one is being prosecuted, and, as peace talks on Syria inch along, there is little sign of justice any time soon.

Global impunity?

Syria of course, is just one example. Hardly a week goes by in Geneva without one UN report or another sounding the alarm about violations “amounting to war crimes or crimes against humanity” taking place somewhere.

In September alone, a UN report on Burundi presented evidence of crimes against humanity, the UN Human Rights CouncilExternal link ordered an investigation into alleged war crimes in Yemen, and the UN Human Rights Commissioner described the violence against Myanmar’s Rohingya community as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

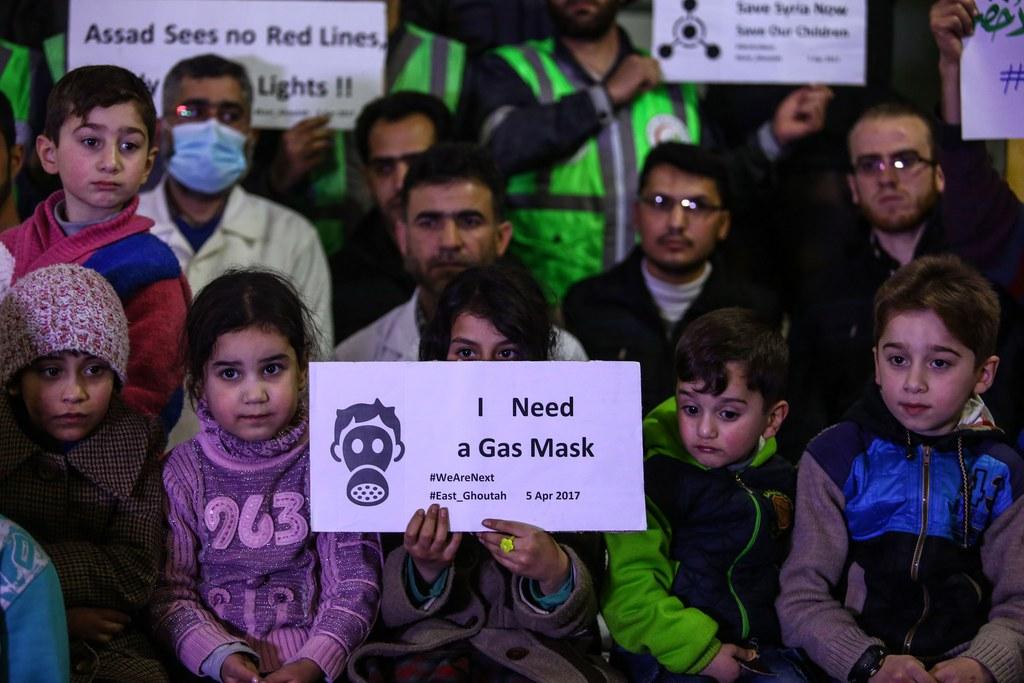

And last week, on the same day as the UN’s report on the Sarin gas attack, the UN Human Rights Commissioner voiced his outrage at the situation of civilians in the besieged Damascus suburb of Ghouta. Almost wearily, it seemed, Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein reminded the warring parties that “the deliberate starvation of civilians as a method of warfare constitutes a clear violation of international humanitarian law, and may amount to a crime against humanity and/or a war crime”.

So are more war crimes taking place? And is there more impunity? Philip Grant, director of the Geneva based non-governmental organisation (NGO) Trial InternationalExternal link, is not sure.

“There should be some scientific analysis of this,” he says. “I don’t think there is more impunity, and at least you have institutions, and growing numbers of countries, which are taking this seriously.”

Trial International is one of a number of NGOs which try to gather evidence on alleged perpetrators of war crimes, and use available law to bring about prosecutions. Methods of bringing accused to justice include international tribunals, such as that for former Yugoslavia or Rwanda, the International Criminal Court, and, increasingly, individual countries applying the concept of “universal jurisdiction” in which some crimes are deemed so serious that states can claim jurisdiction over an accused person regardless of his or her nationality, and regardless of where the alleged crime was committed.

Complex cases

Trial International is working on just such a case right here in Switzerland. Its complexity, and its age, are indicative of just how laborious the legal process around alleged war crimes can be.

In 1982, long decades before the Sarin gas attack on Khan Sheikhoun, other alleged war crimes took place in the Syrian town of Hama, when the Syrian army, commanded by General Rifaat al Assad – the uncle of Syria’s current leader – entered Hama to put down an uprising.

Thousands of people, many of them civilians, were reportedly killed. Rifaat al Assad now lives in France, and has visited Switzerland regularly in the past. Trial International collected evidence on Hama from eyewitnesses and victims and gave it to the Swiss Office of the Attorney GeneralExternal link, which opened an investigation in 2013.

So far, however, Trial International is disappointed by what it sees as a lack of progress, and went public with its frustration last month. Swiss prosecutors say the case is complicated and will take time, but some of the alleged victims believe their suffering is being neglected. Describing the Swiss investigation as “sluggish” so far, Philip Grant added “it sends a dangerous message to today’s belligerents in Syria. It must be absolutely clear to them that they are not beyond the reach of justice”.

Liberia success

But another Swiss based organisation has had recent success bringing human rights violators to court. Civitas MaximaExternal link tries to track suspected war criminals, many of whom flee their countries when the conflict is over. United States authorities realised that a notorious Liberian warlord, Mohammed Jabbateh, known as “Jungle Jabbah”, was in the United States, where, years earlier, he had been granted asylum.

The prosecutor needed to prove that Jabbateh had lied to US asylum and immigration authorities over his involvement in Liberia’s civil war. To do so, 20 witnesses travelled from Liberia to the United States, providing horrific evidence of Jabbateh’s involvement in murder, rape, and cannibalism.

On October 18th a US court found Jabbateh guilty: on two counts of fraud, and two counts of perjury. His offence in the US: not war crimes, but falsely claiming asylum on the grounds that he had been among the persecuted, rather than a persecutor. Nevertheless, Jabbateh has been convicted, and faces a prison sentence of up to 30 years.

In a statement, Civitas Maxima hailed the case as hugely important because it marked “the first time that Liberian victims were able to testify about their experience of the atrocities committed during the first Liberian civil war in a public and fair trial”.

Victims need patience

The cases of Rifaat al Assad and Mohammed Jabbateh had different outcomes, but they are both indicators of one thing: brutal, horrific acts of violence, which often take just minutes to carry out, can take decades to prosecute.

“In the end, most people get away,” admits Reed Brody of Human Rights WatchExternal link and the International Commission of JuristsExternal link.

Brody, too, has recently worked on a landmark trial of Chad’s former president, Hissène Habré. As he points out, this was a “victim-led trial” in which those who suffered under Habré’s rule were determined to get justice.

After years of legal attempts in Belgium and Chad – and numerous delays along the way – Habré was finally brought to trial by a special court in Senegal last year. He was convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life in prison, the first time a head of state had ever been prosecuted in the courts of another country.

Brody regards this case, and those brought by Trial International and Civitas Maxima, as a positive sign that, even though many suspected war criminals do get away, the attitude towards such crimes is much more severe, and as a consequence, the infrastructure to support prosecution is becoming increasingly rigorous.

“It is a signal that the international community is willing to prosecute,” he points out.

All that paperwork in Geneva does yield something positive, he believes.

“All those declarations and reports coming out of Geneva reflect the norm, that if you commit such crimes you should be brought to justice.”

You can follow Imogen Foulkes on twitter at @imogenfoulkes, and send her questions and suggestions for UN topics.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.