When the death of a diplomat challenged Swiss neutrality

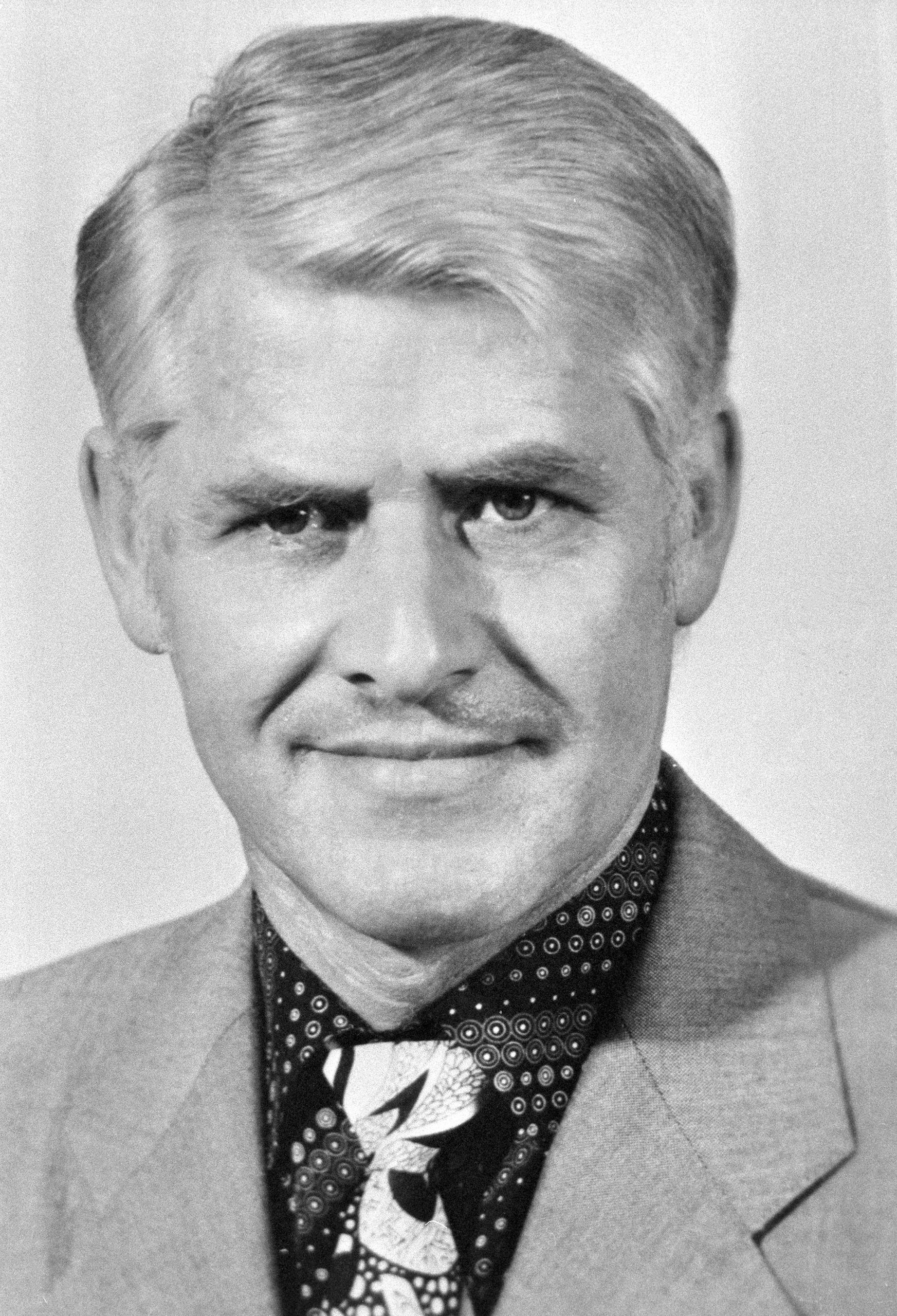

On this day 40 years ago, Hugo Wey was shot dead on his way to work in El Salvador. The death of the Swiss chargé d’affaires against a background of growing tension in the Central American nation showed that Swiss neutrality was not enough to protect diplomats from the fallout of local conflicts.

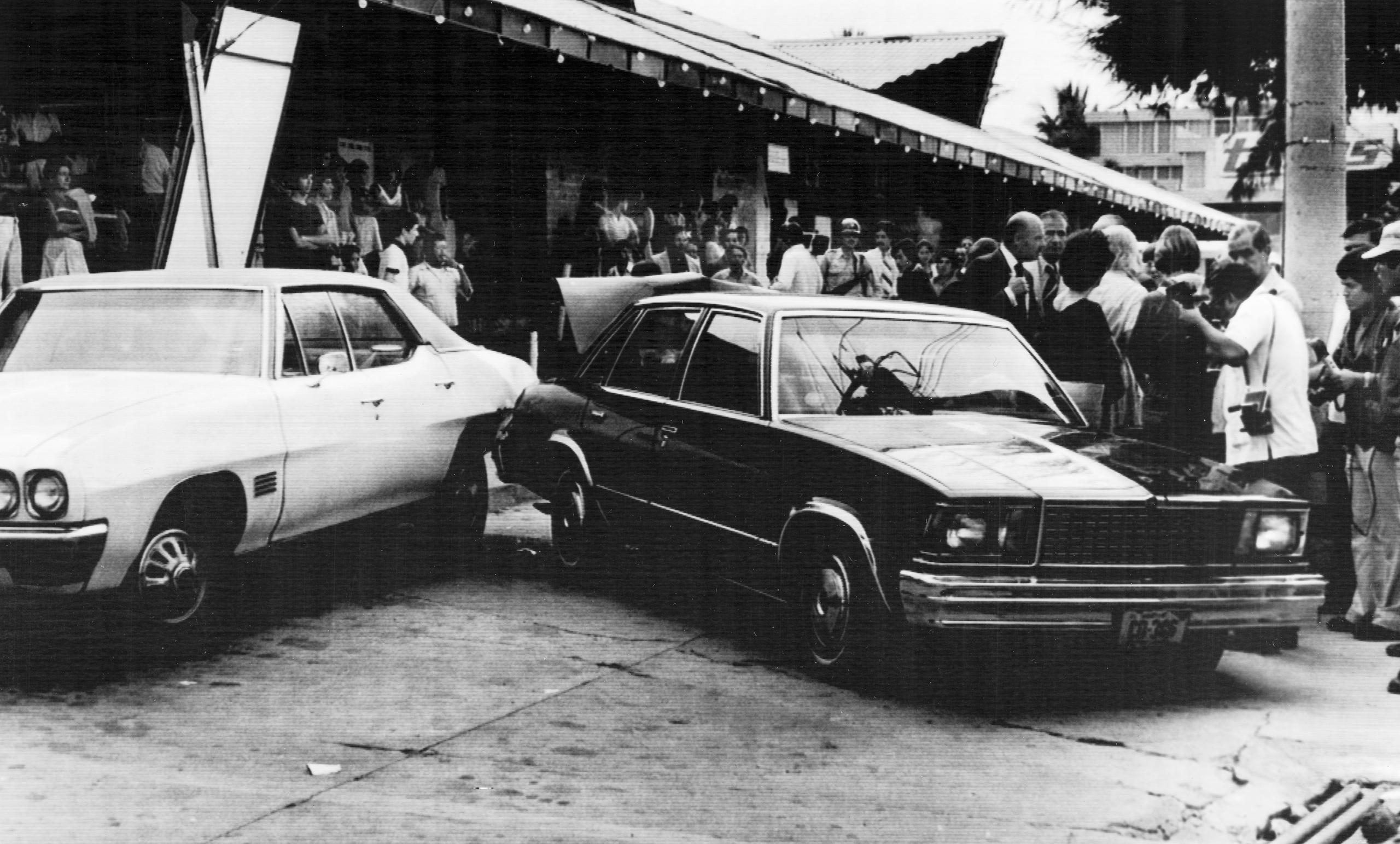

On the morning of May 30, 1979, Hugo Wey left his home as usual to go to the embassy in San Salvador by car. At one point in his journey, another car cut in front of him, blocking his path. The diplomat quickly reversed to get away, but the attackers opened fire. Wey was struck by a single bullet and died.

The reasons behind the attack were never cleared up. Witnesses questioned by police had arrived on the scene after the shooting, and their statements were contradictory. The investigators concluded that it had been a botched attempt at a kidnapping.

No organisation ever claimed responsibility for the attack, but it was attributed to Marxist guerillas.

“Whoever murdered Hugo Wey, the attack on him was a clear indication that neutrality would not preserve Switzerland from being caught in the middle of conflict situations,” says Sacha Zala, head of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland, DodisExternal link.

An increasingly anxious Swiss community

At the end of the 1970s, Central America was in the grip of violent conflicts, fed by the blatant socio-economic inequalities that characterised the region.

In El Salvador, the rise to power of General Carlos Humberto Romero in 1977 brought a wave of brutal repression against trade unions and other organisations on the left, which added to the tensions already existing for quite some timeExternal link. Students, workers and peasants took to the streets to protest against the regime, with the support of circles within the Catholic Church.

The conflict did not stop outside the offices of the Swiss mission. In April 1978, the embassy was temporarily occupiedExternal link by militants of the Bloque popular revolucionario, the mass organisation of the Marxist guerilla movement. Similar actions took place at the embassies of Venezuela, Panama and Costa Rica, and in San Salvador cathedral.

False sense of security

After the events in April 1978 and the kidnappings of several foreign businessmen, concern was mounting in the Swiss community in El Salvador. The families of four Swiss citizens working for a branch plant of the Eternit company temporarily left the country for Guatemala after receiving threats. Another couple moved temporarily to California.

A memo written by the Swiss foreign affairs ministryExternal link in May 1980 described the gravity of the situation in the capital city at the time of Hugo Wey’s demise:

“Based on reports from the murdered man in the days immediately preceding his death, it is apparent that at that time San Salvador was close to civil war […]. Occupations of embassies, politically motivated kidnappings, demonstrations that ended in violence, threats made to diplomats and industrialists had long been typical of the situation in the country, and in the time leading up to the murder, their intensity and danger had increased.”

Wey, who had arrived in the country in May 1978, noted thatExternal link, in general, citizens of “democratic, neutral and humanitarian Switzerland” in El Salvador tended to feel safer than other foreigners living there. But he added, somewhat prophetically: “I believe that we are lulling ourselves into a false sense of security.”

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.