Unchecked empires: who watches Geneva’s million-franc foundations?

Wealthy donors come from around the world to create their non-profit foundations in Geneva, where they benefit from a flexible legal framework. Where does their money come from, and where does it go? It is the job of supervisory authorities to find out. But Geneva’s philanthropists could easily slip through the system’s many cracks. (Part 2).

Part 2: Who monitors Geneva’s foundations and why that matters

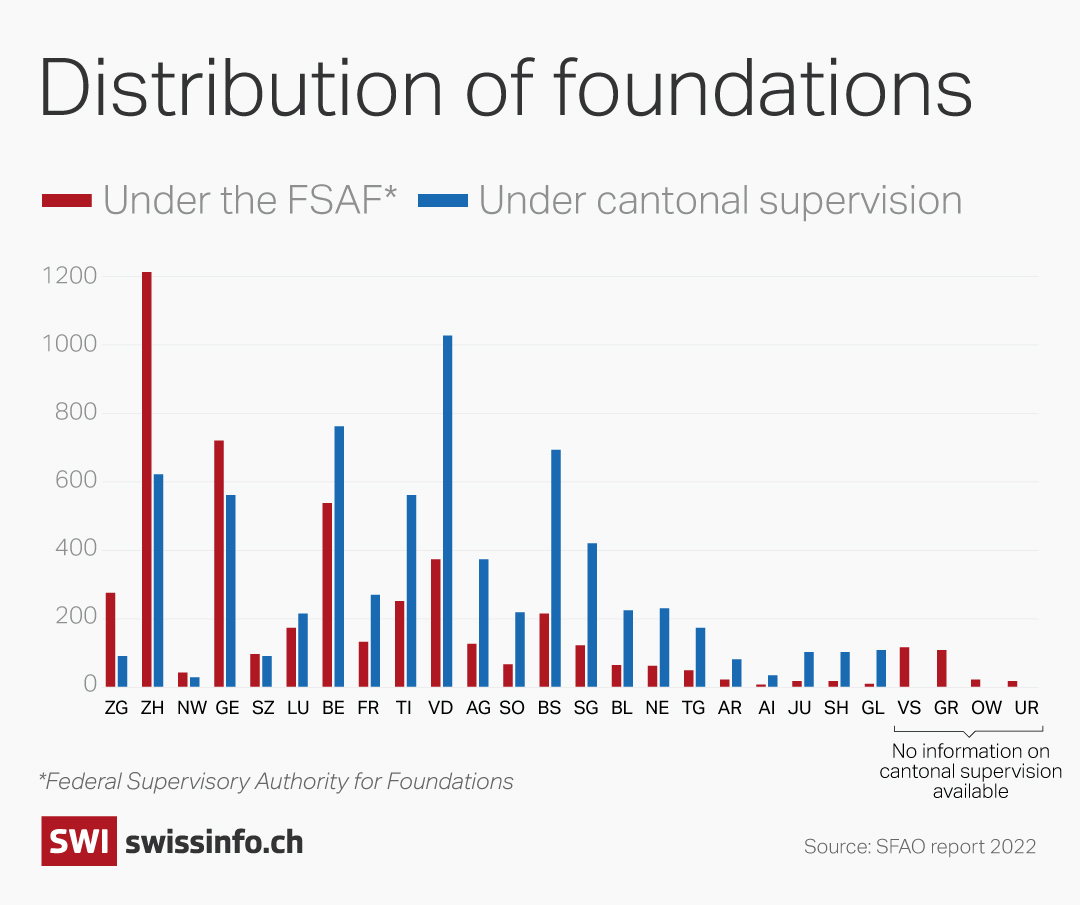

In Geneva, two authorities are in charge of monitoring foundations: the Federal Supervisory Authority and the Cantonal Supervisory Authority. Foundations report either to one or to the other, depending on the area they cover. Structures that operate nationally or internationally are supposed to report to the federal authority. Those that work locally should be attributed to the canton. However, the goals declared by foundations are flexible, and this logic can be manipulated to best serve the donors’ interest. “For example, some foundations declare a national or international scope in their goals because they plan to expand but end up only working in Geneva. Still, they report to the federal authority,” says Jean Pirrotta, director of Geneva’s cantonal supervisory authority.

These two institutions follow different legal procedures and requirements. Between them, there is no coordination and barely any communication. This fragmented landscape creates the perfect loopholes for foundations wishing to exploit the system. “Some foundations may hire specialised lawyers to advise them on the authority that proposes the easiest supervisory process,” says Laurent Crémieux, an expert of the Swiss Federal Audit Office.

‘You could operate a business and pass it off as a non-profit.’

More

Unchecked empires: who watches Geneva’s million-franc foundations?

In 2021, Crémieux supervised an audit of the Federal Supervisory Authority, whose task was to monitor Geneva’s 791 non-profits that handle CHF17 million. He depicts an alarming situation. “The federal authorities mainly operate formal checks and rarely monitor a foundation’s activities beyond its founders’ declarations. If all the papers are in order, the foundation gets a green light,” he says. “Someone could operate a business and pass it off as a non-profit, and it would go undetected.”

Another issue is the many years of delay in processing a foundation’s documentation. Despite the increase in staff, a constant surge in the number of foundations to supervise means that a long-term backlog remains. In the meantime, unmonitored foundations are free to continue their activities.

Since the previous audit, which had already flagged most of these issues in 2017, Crémieux regrets that very little has changed at the federal level. One of the only areas of improvement over the past five years is the creation of a digital system to process submissions. Until 2022, foundations had to send their paperwork via post.

When authorities refuse to supervise problematic foundations

While the federal system is overwhelmed, monitoring activities appear to run more smoothly at the cantonal level. Jean Pirrotta, the director of Geneva’s Cantonal Supervisory Authority, manages a team of 14 people to supervise 600 foundations and 200 pension funds. He assures that there is no delay in the treatment of submissions and notes that his team’s checks are thorough but not invasive. “We can’t conduct in-depth inquiries into all foundations, but when a risk appears, we do investigate.”

Geneva’s Audit Court, whose role is to control cantonal administration, disagrees. In 2011, the court stated that the documentation the authority receives “is insufficient to understand the activity and operation of the foundations and to monitor them adequately.” An assessment that the director understands and has been working on. “Things have changed since then,” Pirrotta argues. Asked what he could improve in his work in Geneva, Pirrotta responds, “Nothing.” For him, the risk of foundations mismanaging their wealth is vastly overestimated. He describes the foundation sector in Geneva as “healthy” and cases of abuse as “rare.”

But is fraud really rare, or is it rarely detected? Pirrotta admits, “If we notice something suspicious, we won’t take the foundation under our surveillance. We had the case of a foundation set up by investors from foreign countries and we suspected tax evasion, so we didn’t take it on”, he explains. “We didn’t consider ourselves competent in this context.” When asked what happens to non-profits they reject, Pirrotta takes the example of a foundation that went unsupervised for 20 years, as all authorities refused to monitor it.

A disjointed system

The supervisory authorities’ shortcomings are further amplified by their inability to communicate with other state experts involved with foundations. For example, there is no communication between supervisory bodies and the finance department. “In case of money laundering suspicions, monitoring services are not allowed to consult with the competent authorities,” explains Crémieux. This opacity between anti-money laundering experts and their supervisory counterparts deprives monitoring authorities of precious insight into the malpractices they may face. “If you are a legal expert, with no in-depth knowledge of embezzlement, money laundering, tax optimisation or asset management, you can’t easily identify these violations,” regrets Crémieux.

The same separation applies between the federal supervisory authority and the canton’s tax department, the sole decision maker on a foundation’s public utility and potential tax exemption. “This is due to tax secrecy, a value that supersedes access to any other type of information in Switzerland and Geneva., he continues.

And the secrecy extends to the Federal Audit Office itself. In 2021, Laurent Crémieux and his team asked to consult the canton’s tax information but were denied access. “We were thus unable to verify that the legal prescriptions in terms of tax exemptions were applied properly and homogeneously throughout the country.”

This disjointed system allows for regulatory loopholes that complicate oversight and enable abuse.

Assessing the risk

Unsurprisingly, data shows that supervisory authorities don’t often take repressive measures against foundations.

Six interviewees SWI reached out to for this story argue the lack of reported abuse is a sign that foundations are clean. But for Laurent Crémieux, the probability of foundations abusing their privileges is challenging to evaluate. “That’s always the difficulty with risk assessment. If you don’t have a risk analysis, it’s hard to know if the risk is high or not.”

In the audit his team conducted, two problematic cases came to light: a foundation created by a pharmaceutical company with the goal of raising awareness about a disease led the auditors to suspect it was nothing but a cover for promoting and selling its own medicine. The audit pointed out another foundation that received donations of millions of pounds from a single donor without these donations being investigated. “These are real cases,” insists Crémieux.

However, for Swiss Foundations, an umbrella institution representing 220 foundations in Switzerland, the current extent of foundations’ supervision is “satisfactory.” Patricia Legler, legal and politics lead for the organisation, points out the danger of too many constraints imposed on foundations that represent no risk, “too much control means foundations will spend money and resources trying to respond to surveillance requests rather than on their philanthropic work.”

At the moment, the supervision balance seems tipped towards freedom rather than accountability for Swiss philanthropic foundations, but this may change in the future. When contacted, the Federal Supervisory Authority announced that they had initiated a reorganisation process both in terms of human resources and procedures, in line with the recommendations of the 2022 Federal Audit Office report.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.