Jain Haunted by Rainmaker Past as Deutsche Bank Fines Multiply

March 26 (Bloomberg) — Anshu Jain won the job of Deutsche Bank AG co-chief executive officer after leading its investment bank to record profit. Two years later that rainmaker role is coming back to haunt him.

At the heart of the challenge for the one-time derivatives salesman is declining market share in fixed-income and potential fines arising out of industrywide investigations into the alleged manipulation of interest rates, currencies and gold after the Frankfurt-based bank spent at least $6 billion on settlements and penalties since 2009.

The alleged improprieties, most of which date to when Jain led the investment bank from 2004 to 2012 and Josef Ackermann was CEO, have strained relations with regulators and prompted probes of business practices from Buenos Aires to Milan.

“Ghosts of the past are catching up with the company,” Michael Huenseler, who helps manage 11 billion euros ($15.2 billion) including Deutsche Bank shares and bonds at Assenagon Asset Management SA in Munich, said in a phone interview. “Many of the problems they face hail from the investment bank, which Jain ran. He’s under pressure to keep Deutsche Bank out of the headlines and focus on fulfilling its potential.”

While Jain and co-CEO Juergen Fitschen point to their success meeting targets on capital and costs, they will fail to meet a key pledge to shareholders — increasing return on equity to more than 12 percent next year from 1.2 percent in 2013, according to 16 analysts’ estimates compiled by Bloomberg.

Right Man

Deutsche Bank, Europe’s biggest investment bank by revenue, this month posted a 1.36 billion-euro fourth-quarter loss as debt-trading revenue slumped 31 percent and the company added to its legal costs, which totaled 3 billion euros in the full year. JPMorgan Chase & Co. is poised to usurp the firm as global leader in fixed-income as Jain and Fitschen focus on regulatory matters and withdraw from unprofitable businesses.

Jain, 51, who hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing, said at the company’s annual press conference in January that he considered himself accountable for excesses at the investment bank. Still, he said employees and clients believe he’s the right man to lead cultural change at the bank.

“We are now 18 months into a 40-month journey,” Jain said in a phone interview on March 14, referring to the strategy that he and Fitschen presented in September 2012. “We are stabilizing this bank, creating the equity buffers and dealing with the legacy issues.”

Fitschen, 65, declined through a spokesman to comment.

Least Capitalized

The co-CEOs inherited the least capitalized of the world’s nine biggest investment banks when they took over in 2012 from Ackermann, who had led Deutsche Bank for a decade.

Jain, who has a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, joined Deutsche Bank in 1995 from Merrill Lynch & Co., following his mentor, Edson Mitchell. After Mitchell died in a plane crash in December 2000, Jain took over as head of debt. Ackermann promoted him to lead the combined debt, equity sales and trading unit in 2004.

Jain thrived under Ackermann, who sought to create a global securities firm capable of competing with the likes of Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

The Swiss-born former CEO also relied on the investment bank to deliver an increasing share of profit. The division made up 53 percent of the company’s revenue in 2004, the year Ackermann promoted Jain, company filings show. Jain built Deutsche Bank into a bond-market powerhouse and in 2010, the year he became sole head of the investment bank, the unit supplied 61 percent of the firm’s income, the filings show.

Book Value

Concern among investors that litigation and lower debt- trading revenue will hurt the bank’s finances is reflected in the share price, which has risen 1.8 percent over the past 12 months compared with a gain of 19 percent for the Bloomberg Europe Banks & Financial Services Index.

Deutsche Bank trades at 0.6 times book value, a measure of what investors expect to receive should it liquidate its assets. That’s less than the 0.99 times average for the index and lower than all 43 of the companies it tracks except Raiffeisen Bank International AG, the Austrian lender with the biggest foreign presence in Ukraine, Unione di Banche Italiane ScpA, Italy’s fourth-largest bank, where nonperforming loans have jumped, and Edinburgh-based Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc.

Suicide Inquest

The gloom isn’t abating. Yesterday, Munich prosecutors raided the bank’s headquarters as part of a new probe of fraud allegations stemming from a 12-year-old dispute with the late Leo Kirch, a German media magnate. Separately, a psychologist’s report read at a coroner’s inquest in London into the suicide of William Broeksmit, showed that the retired Deutsche Bank risk executive was “very anxious about authorities investigating areas of the bank at which he worked.”

Broeksmit wasn’t under suspicion of any wrongdoing in any matter, Kathryn Hanes, a spokeswoman for Deutsche Bank, said in an e-mailed statement after the inquest yesterday.

Jain and Fitschen have said that Deutsche Bank is undervalued because it will settle most outstanding probes and lawsuits this year and is ahead of schedule in meeting next year’s goals for cost reduction and capital. Jain told investors on a conference call in January that the bank still plans to meet the goals he and Fitschen set in September for costs, capital and return on equity in 2015.

Twenty-one of 44 analysts surveyed by Bloomberg recommend investors buy Deutsche Bank shares, while seven say sell.

‘Unsolved Challenges’

“We feel the new management team under Anshu Jain has been left with a lot of unresolved challenges post the previous CEO’s departure,” Kian Abouhossein, a London-based analyst at JPMorgan, wrote in an e-mailed report on March 17. “We rate the current management team highly to resolve these issues.”

Abouhossein reiterated his “overweight” recommendation on the company. He wrote the report after JPMorgan hosted a meeting between Jain and investors. The co-CEO told investors that Deutsche Bank’s return in fixed-income, currencies and commodities was 15 percent in 2013 and that the business will continue to provide income surpassing its cost of equity, according to the report.

Scandals involving Deutsche Bank and other global lenders including Barclays Plc over alleged manipulation of interest rates and currency benchmarks have prompted regulators, the German media and politicians in Berlin to step up scrutiny.

‘Take Accountability’

Banking-industry supervisor Bafin, which reports to the German Finance Ministry, found that Deutsche Bank’s management didn’t adequately investigate and address the firm’s role in the alleged rigging of interest rates, Der Spiegel reported on Jan. 5, citing a leaked document. Two days later, Die Welt newspaper said Bafin criticized the bank in a separate letter for initially providing incorrect information about a derivatives contract with Italy’s Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA.

Deutsche Bank said it’s cooperating with regulators and that accounting of the Monte Paschi deal was confirmed by auditor KPMG. Sven Gebauer, a Bonn-based spokesman for Bafin, declined to comment on the press reports or the status of Deutsche Bank’s relationship with the German regulator.

“Yes there were excesses, yes I have to take accountability, and I do take accountability,” Jain told reporters at the January press conference. “If you want people to lead in investment banking, I doubt you’d find people with experience that wouldn’t have similar accountabilities.”

Jain, who used to sell products such as interest-rate swaps, hasn’t been accused by regulators or prosecutors of any involvement in the rigging of rates and currencies. An internal probe into the setting of the benchmark London interbank offered rate, or Libor, cleared top management of any wrongdoing.

Wooing Politicians

Deutsche Bank isn’t the only financial firm dealing with legal headaches. In November, JPMorgan, the biggest U.S. bank by assets, agreed to pay a record $13 billion to resolve U.S. Justice Department probes into the sale of mortgage bonds.

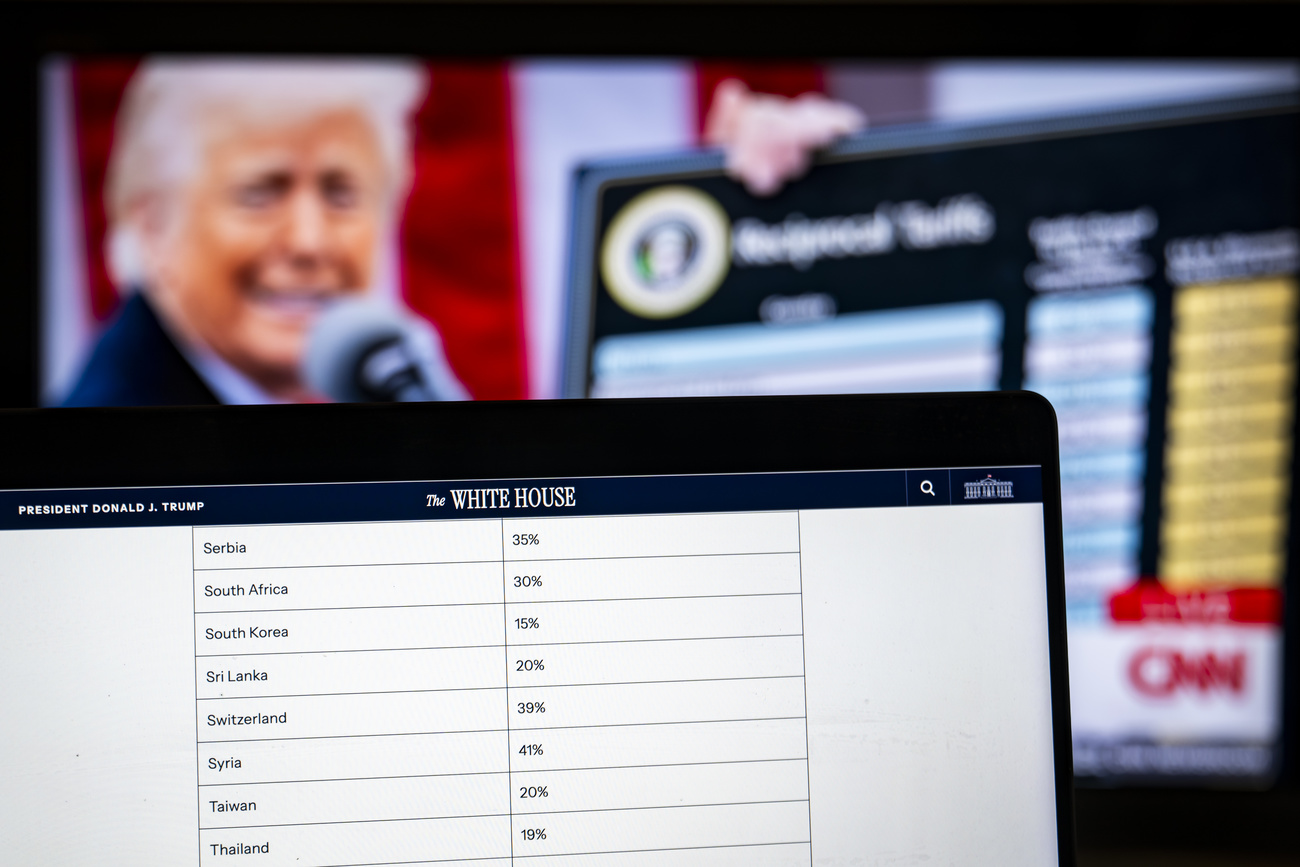

HSBC Holdings Plc, Europe’s largest bank by assets, agreed to pay $1.92 billion in December 2012 to settle a U.S. money- laundering investigation. The same month, Zurich-based UBS AG was fined about 1.4 billion Swiss francs ($1.6 billion) by U.S., U.K. and Swiss regulators for trying to rig interest rates.

The co-CEOs spent several days in Berlin last month wooing politicians at meetings in parliament and at events tied to the publication of books about the concentration of economic power and former Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder. The visit came amid differences with Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government over plans to tighten bank regulation.

Those proposals, which include ensuring firms don’t use client deposits for some investment-banking activities, led to a public spat between Fitschen and Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble in December, when Fitschen called Schaeuble “irresponsible” and “populist.”

Tough Sell

Deutsche Bank’s legal woes make it more difficult for Jain to convince shareholders that his strategy is the one the bank should follow, said Michael Seufert, an analyst at Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale in Hanover, Germany.

“The situation could get more difficult for management depending on the fallout from legal issues and whether the market comes back and supports their business,” said Seufert, who recommends investors hold the shares. “It’s hard to escape unharmed if you’re under fire from all sides.”

Huenseler at Assenagon said Jain faces an uphill struggle.

“It’s tough to show shareholders that Jain was responsible for the business but won’t take responsibility by quitting,” the fund manager said.

Bob Diamond stepped down as CEO of London-based Barclays in July 2012 after his firm was fined 290 million pounds ($479 million) for rigging Libor, even though he wasn’t accused of wrongdoing. John Hourican quit as investment-banking chief of RBS in the wake of the scandal, in which he wasn’t implicated.

‘Fall Guy’

Bill Fries, a managing director at Santa Fe, New Mexico- based Thornburg Investment Management Inc., which oversees $94 billion of stocks and bonds, said Jain’s departure would be unfair unless he was directly complicit in manipulating markets.

“I’m not so sure that someone who had nothing to do with the issue should have to be the fall guy just because in the short term it would be an expedient to get the issue behind us,” Fries said in a telephone interview.

Thornburg owned more than 10.4 million Deutsche Bank shares at the end of January, making it the company’s eighth-largest investor, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Jain, an Indian-born British citizen and the bank’s first non-European CEO, also faces the challenge of prejudice against foreigners in Germany, according to Seufert.

“Jain’s heritage is still an issue in public and political circles,” Seufert said. “It’s sad, but Germany isn’t far enough along in terms of mentality. The country can be a bit provincial when compared with Switzerland, where you have executives with very different backgrounds.”

Profit Target

European investment banks have given up trading desks and fired bankers as more stringent capital requirements and a drop in demand since 2007 make some businesses unprofitable.

“That consolidation has mostly benefited the U.S. firms, but also played into Deutsche Bank’s hands in Europe,” Andreas Meissner, who manages about 50 million euros of stocks and bonds at Andreas Meissner Vermoegensmanagement GmbH, said in a telephone interview from Hamburg. “They’re ultimately going to be handling more of the available business.”

Deutsche Bank will fail to meet a 2015 target of more than 12 percent return on equity, or profit as a percentage of shareholder equity, according to 16 analysts’ estimates compiled by Bloomberg that ranged from 6 percent to 9.9 percent.

Litigation Risk

Jain and Fitschen may decide to push back the profit target until 2016 or beyond, rather than risk missing it, following UBS and Barclays, said Andreas Plaesier, an analyst at M.M. Warburg in Hamburg who recommends investors hold the stock.

“Litigation is definitely one of the factors that could keep them from fulfilling their target,” Andrew Stimpson, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods said in a phone interview from London. “They also face a drastically changing investment- banking environment, especially in fixed-income.”

The co-CEOs have made better progress meeting goals for cutting costs and increasing capital.

They reduced expenditures for the 18-month period from mid-2012 to the end of 2013 by 2.1 billion euros, 500 million euros more than planned. They aim to have reduced annual costs by 4.5 billion euros by the end of next year.

Capital Adequacy

Deutsche Bank also increased its capital-adequacy ratio under Basel III rules, a key measure of financial strength, to 7.8 percent in 2012, exceeding a goal of 7.2 percent. The ratio of 9.7 percent at the end of last year, achieved partly by a share sale of 3 billion euros in April, compares with a target for the end of March 2015 of more than 10 percent.

UBS had a capital-adequacy ratio of 12.8 percent at the end of 2013, Credit Suisse 10.3 percent and Barclays 9.3 percent, data compiled by Bloomberg Industries show.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which sets global banking standards, suggests big banks hold equity equivalent to 7 percent of their risk-weighted assets by 2019. The most systemically important lenders, including Deutsche Bank, face additional capital buffers of as much as 2.5 percent.

Deutsche Bank’s $6 billion bill for fines and settlements in the past five years, the majority of which originated from the investment bank, compares with about $24.8 billion in pretax profit at the unit over the same period, calculations by Bloomberg based on company filings show.

Three Settlements

The three biggest settlements came in the past three months — a 725 million-euro fine in December for alleged manipulation of euro and yen interest-rate derivatives; 1.4 billion euros the same month for failing to adequately disclose U.S. mortgage- backed securities; and about 925 million euros in February over claims the bank contributed to the 2002 demise of Kirch’s German media group.

Deutsche Bank acknowledged infringements of the European Union’s competition law in the rate-rigging case. It neither admitted nor denied guilt in the other two matters.

The bank’s cash reserves of 1.8 billion euros for legal costs won’t be enough, said Stimpson at KBW, an investment bank owned by Stifel Financial Corp. Jain and Fitschen will probably spend an additional 1.2 billion euros on fines and settlements this year, 900 million euros in 2015 and 700 million euros in 2016, he said.

“Deutsche Bank still has all that litigation risk hanging over it,” said Meissner, the Hamburg-based fund manager. “They can’t shake this just yet.”

Meissner said he reduced the shares he holds in Deutsche Bank in January because of concern that the bank’s legal costs are too high.

Libor, Currency

Deutsche Bank still faces probes by U.S. and U.K. regulators into alleged attempts by its traders to manipulate Libor and currency rates. German banking regulator Bafin interviewed Deutsche Bank employees as part of an investigation into potential manipulation of gold and silver prices, a person with knowledge of the matter said in December.

The company says it’s cooperating with regulators.

Deutsche Bank fired or suspended at least four currency traders this year for inappropriate communication after reviewing their e-mails, according to people with knowledge of the matter. That follows the dismissal or disciplining of at least seven employees since the end of 2011 as part of an internal probe into alleged attempts to rig interest rates.

In December, the firm agreed to forfeit 221 million euros to end a derivatives contract with Monte Paschi that helped obscure losses at the Italian bank.

Police Raid

A year earlier, about 500 German police and tax investigators raided Deutsche Bank’s headquarters in an investigation of alleged tax evasion in carbon markets. The company still faces lawsuits claiming it didn’t provide adequate disclosure when selling mortgage-backed securities.

Deutsche Bank has said it is cooperating with German authorities probing carbon markets, that any errors in its tax declarations were corrected in a timely manner and that it is supplying information to regulators related to U.S. mortgages.

The legal investigations come as Deutsche Bank has lost ground in global institutional fixed-income trading. Its market share shrank to 10 percent last year from 10.7 percent in 2012, Greenwich Associates said in a January study. While the company remained the world’s biggest bond dealer, JPMorgan raised its share to 9.2 percent and Citigroup Inc. to 8.9 percent, the Stamford, Connecticut-based research company said.

Earnings ‘Handicapped’

Earnings “in the next quarter or two are going to be handicapped by the contraction that they’ve suffered in fixed- income,” said Fries at Thornburg. “That’s a cyclical business, and while there are some secular changes, we do think with attention to costs, they’ll right-size that business and when volumes do come back, there’ll probably be some leverage.”

Cost-cutting by Jain and Fitschen would help Deutsche Bank’s earnings. Pretax profit will probably jump to 4.7 billion euros this year and 7.3 billion euros in 2015 from 1.46 billion euros in 2013, according to the average of 19 analysts’ estimates compiled by Bloomberg.

Jain isn’t the first Deutsche Bank CEO to come under fire. Ackermann survived public scandals and criticism and failed to meet profit targets. He drew the ire of the government in 2005 by announcing 5,200 job cuts even as profits rose. Franz Muentefering, a former vice chancellor, criticized the former CEO for trying to bring “profit to the few at the expense of many,” calling his behavior “antisocial.”

“There’s a long tradition of hostility toward Deutsche Bank CEOs and they have to endure situations others couldn’t, but it’s reached an inappropriate level of demonization” with Jain, Falko Fecht, a professor of financial economics at the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, said in a phone interview. Lambasting bankers for rate-rigging is unfair given that regulators allowed such excesses to happen, he said.

‘Relatively Harmonious’

Deutsche Bank’s board wouldn’t have named Jain co-CEO if it was concerned that he would be implicated in wrongdoing and was aware legal costs would mount, Fecht said. Jain, Fitschen and Paul Achleitner, chairman of the supervisory board, also appear to be working well together, he said.

“They look relatively harmonious at the moment, and that’s because the bank’s leaders each have a clear area of focus,” Fecht said. “If Jain wants to stay on as CEO, possibly as sole CEO, he needs to boost his credentials as a commercial banker and not just be seen as an investment banker. The bank needs to work on its other businesses.”

Jain has said he’s relying on Deutsche Bank’s transaction banking and asset- and wealth-management businesses to boost profit and help reach next year’s return-on-equity goal.

Still, the investment bank, which accounted for 43 percent of Deutsche Bank’s revenue last year, remains a key part of the company’s strategy. Jain is shrinking assets there to raise capital levels and has said he is giving up businesses if they don’t meet his goal of cultural change.

Culture Change

“Cultural change is our very strong attempt at Deutsche Bank to make sure that in five years we’re less likely to be talking about issues created in 2014,” Jain said in the March 14 interview.

The challenge is ensuring Deutsche Bank doesn’t lose out to U.S. competitors in the long term, according to Seufert at Norddeutsche Landesbank, who recommends holding the stock.

“Deutsche Bank made a bet that it will emerge a winner from sticking it out,” said Seufert. “Until last year, I was convinced the strategy would work, but I’ve become more skeptical. It’s going to be tight.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Nicholas Comfort in Frankfurt at ncomfort1@bloomberg.net To contact the editors responsible for this story: Frank Connelly at fconnelly@bloomberg.net Mark Bentley, Robert Friedman