Switzerland drops the Geneva Initiative. But what’s the alternative?

Twenty years on, Switzerland is turning its back on the Geneva Initiative, which deals with the conflict in the Middle East. It believes that the international political context has changed dramatically and that a “more innovative and effective” approach is needed.

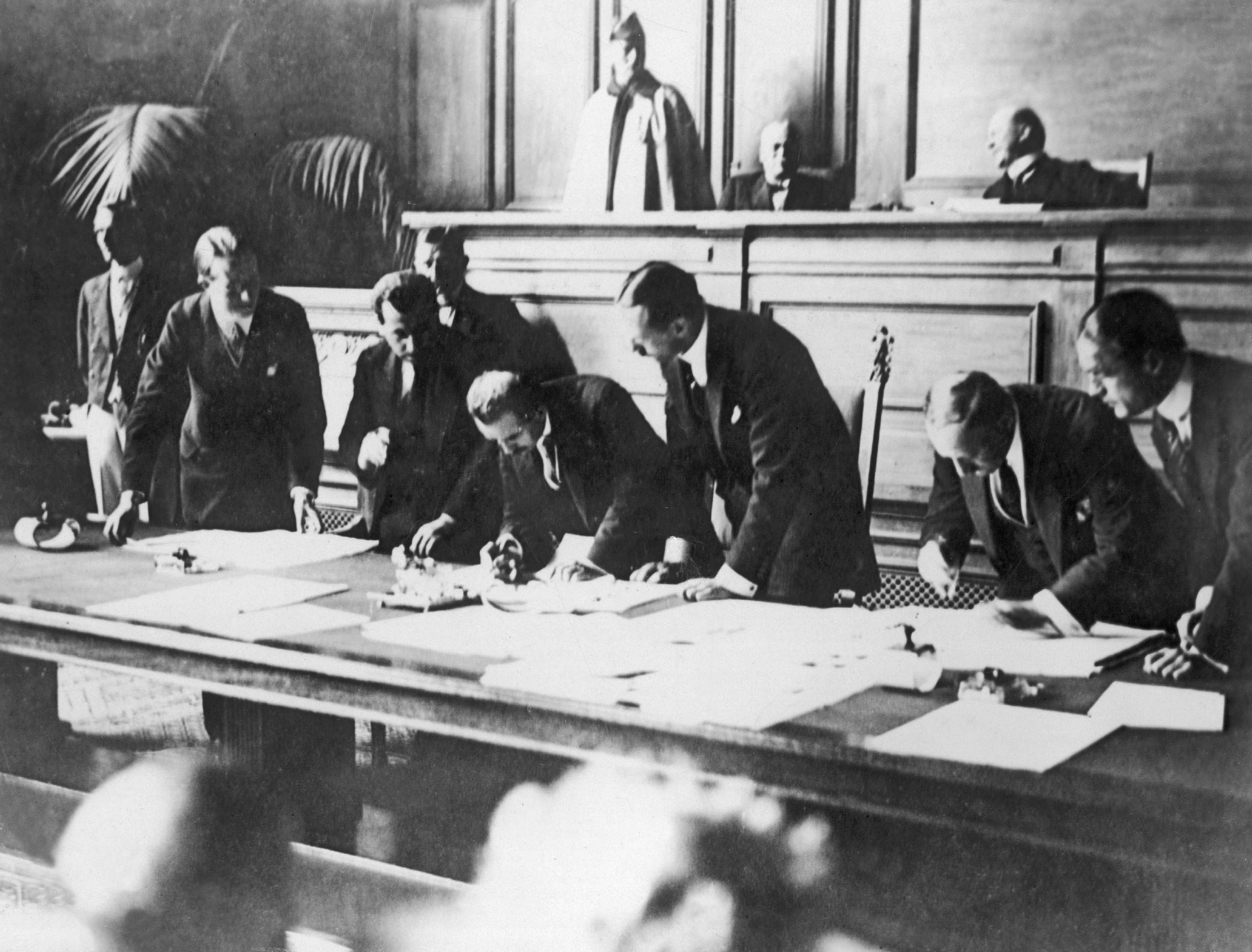

The Geneva Initiative was signed in October 2003 by two former ministers, one Israeli and one Palestinian, under the impetus of Swiss academic Alexis Keller. It sought to provide – if not a definitive solution to the Middle East conflict – then at least a first step towards a global resolution.

It was “the first initiative of its kind that proposed concrete steps to resolve the Middle East conflict”, recalls Mohamed Cherif, former Geneva correspondent for SWI swissinfo.ch, who covered the event at the time.

The Geneva Initiative was above all the brainchild of the Geneva academic Alexis Keller and his father, a former diplomat and banker. From January 2001, the pair became personally and financially involved in the negotiation process, which often took place at the family chalet in the Bernese Alps.

Over two years later, on October 12, 2003, their efforts culminated in a nearly 100-page text signed by Yossi Beilin, a former Israeli minister, and a Palestinian counterpart Yasser Abed Rabbo, in Jordan.

The Geneva Initiative provides for major concessions by both sides and addresses all the substantive issues of the conflict: the status of Jerusalem, the fate of the Palestinian refugees and delineation of the borders.

The text was drafted by members of both Israeli and Palestinian civil society and was distributed to households on both sides. It was supported by former UN secretary general Kofi Annan and former US president Jimmy Carter.

The Israeli government was strongly opposed to the text, and many people criticised what they saw as Switzerland’s “interference” in Israeli affairs.

2003 was the year when the United States invaded Iraq. It was also when the second Palestinian intifada was at its height. This uprising, in which Palestinians attacked Israeli soldiers by throwing stones at them and committed suicide attacks, broke out after the failure of the Camp David agreements in 2000. In retaliation, Israel bombed the Palestinian Authority in Gaza and the West Bank. In total, an estimated 1,000 Israelis and 3,000-5000 Palestinians have died during the violence.

Alexis Keller also remembers the optimism that greeted the initiative, the idea for which was born in Geneva in 2001 and concluded in Amman, Jordan, two-and-a-half years later. “There was an atmosphere of mutual respect and recognition between the two parties, leading to real joy and a feeling of having made history,” he told SWI swissinfo.ch.

However, 20 years after the agreement was signed, it must be acknowledged that it has had no impact on the ground: Israeli settlements are proliferating, and the two countries are locked in a simmering conflict with nearly daily casualties. Switzerland has announced that it will no longer fund the initiative after 2023.

Keller is surprised at this decision. He believes “the text still provides the most complete model for a two-state solution, especially given that the foreign ministry has not announced any concrete alternative”.

More

When the Middle East was reinvented in Switzerland

An atypical initiative

The Geneva Initiative was by no means the first attempt to establish peace between Israel and the Palestinian territories. There were the Oslo Accords I and II in 1993 and 1995, the Camp David Summit in July 2000, and a peace plan presented by then US president Bill Clinton in December 2000.

The Geneva Initiative stands out in that it sought to address in a single document the main differences separating the two protagonists, such as the status of Jerusalem, the evacuation of almost the entire West Bank of Jewish settlers, and compensation for Palestinian refugees.

It was intended as a first step towards bringing the then Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, and the head of the Palestinian Authority, Yasser Arafat, to the negotiating table. The approach followed was also innovative, as the text was drafted by members of both Israeli and Palestinian civil society and not negotiated by heads of state.

“It tackles the problems head-on and then integrates the results into a wider process,” Keller said at the time.

Destined to fail?

With hindsight, however, one may ask whether the agreement was not simply destined to fail. It never set off the wave of civil solidarity that the signatories had hoped for.

More

Switzerland condemns violence in West Bank and Israel

Keller mentions three possible reasons why the process failed. “Switzerland was not committed enough, unlike Norway with the Oslo Accords. There was also strong rejection from Israel and a lack of support from the Arab countries,” he said.

Within Switzerland itself, the initiative was divisive from the outset. It was promoted by Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey, but she was isolated within the government and never obtained a parliamentary majority in support of the process.

This lukewarm backing from Switzerland, which further dwindled over time – its contribution fell from CHF1 million ($1.15 million) in 2009 to CHF180,000 in 2021 – led to a lack of commitment to implementing the initiative on the ground.

The initiative also shows “Switzerland’s naivety and ignorance of the local dynamics that dominate the Middle East”, according to an expert who works on projects with the Swiss foreign ministry and prefers to remain anonymous. It was assumed that the text would be taken up by civil society and relayed by Israeli and Palestinian public opinion, but this never happened.

Switzerland pulls back

An evaluation of the initiative by Switzerland in 2020 concluded that it had become less effective because of a lack of political support on both the Israel and Palestinian sides. In January 2022, the Swiss foreign ministry decided to withdrawExternal link financially from the initiative by the end of 2023.

Instead, Switzerland announced a new strategy for promoting peace and development in the Middle East and North Africa from 2023. Plans are also underway to move the office of its development and cooperation agency from Jerusalem to Ramallah, as requested by Israel.

Switzerland is at pains to stress that the definitive end of the initiative does not signal its disengagement from the region.

Quite the opposite is true, says foreign ministry spokesman Andreas Heller. “The pursuit of a political solution to the conflict in the Middle East is a priority of the federal government’s 2021–2024 strategy for the Middle East and North Africa.” Switzerland spends CHF1.8 million a year on “promoting peace and human rights”, he adds.

With the appointment of a Swiss envoy for the Middle East, the government has also created a new position to “promote concrete solutions in the region”. This special envoy will not replace the regional ambassadors already on the ground.

This change of tack has been widely criticised by experts and NGOs, who accuse the country of zigzagging in its foreign policy in the region. According to Nago Humbert, founder of Doctors of the World Switzerland, the decision to transfer Switzerland’s cooperation office to Ramallah “could be interpreted as implicit recognition of the annexation of East Jerusalem by the State of Israel”.

A statement by Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis during a trip to the region in 2018 followed similar lines. “As long as the Arabs are not prepared to grant Israel the right to exist, Israel will feel threatened in its existence and will defend itself,” he said.

In Keller’s view, the current Swiss approach in the Middle East “masks the opaqueness of Swiss foreign policy, for if Switzerland focuses on humanitarian and development aid, it is in fact going back to what it was doing before the Geneva Accord: not doing politics in a region where everything is political”.

Edited by Virginie Mangin. Translated from French by Julia Bassam.

More

Switzerland’s delicate stances on Israel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.