Can ‘Plan S’ revolutionise access to science?

An ambitious open-access publishing initiative backed by some of the world’s largest research funders came into effect in January. Plan S, as it’s known, has already started to transform the scientific world. But its success depends on continued pressure on big publishers and on getting more influential countries like Switzerland to sign up.

You may never have to pay for scientific research again – that is, if Plan S succeeds. The European-led initiative in effect since January 1, aims to disrupt the scientific research industry by making scholarly papers free online. Supported by over 20 major funders, the initiative launched three years ago, wants to completely change the way research is funded and retributed.

Almost two million scholarly articles are published every year in around 30,000 journals, but only a third of them are freely accessible to readExternal link. For years, public authorities have had to pay publishers to read articles by scientists whose research they funded, who themselves handed over their work free of charge to the same firms. In 2015, Swiss universities paid CHF70 million ($76 million) in subscription licences to access 2.5 million articles behind paywalls. Many of those articles were written by their own researchers.

The Wellcome Trust, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and national research funders like Norway, France and Italy are part of the international consortiumExternal link behind the initiative. They want to ensure that publications resulting from its funding are “immediately made openly available for the entire world to benefit from, free from any embargo periods or paywalls”, according to the initiative’s executive director, Johan Rooryck.

“Plan S has really shaken up the entire academic publishing industry,” says Kamila Markram, director of Frontiers, a Lausanne-based publisher of open-access scientific journals.

Pandemic publishing

Calls to change the lucrative research paper subscription model and for scientific findings to be shared freely and widely have been going on for years. They have recently grown louder though, in part due to pandemics.

In 2015, a group of senior health researchers published an open letterExternal link in the New York Times declaring that the Ebola pandemic could have been prevented if it weren’t for paywalls. They quoted an article published in a subscription-only journal in 1982 that had warned of the risk.

Over the past year, the Covid-19 pandemic has made “crystal clear” the importance of easy access to scientific publications, according to Markram. She notes that the White House made all coronavirus-related research prior to 2020 available online for any researcher. The 200,000 pandemic-related publications that came out last year were all open access.

But when it comes to other life-threatening issues like cancer, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and climate change, Markram points out that only about 20-30% of related research is open-access.

“It’s mind-boggling,” she says.

Resistance to change

The Plan S goal of transforming the academic publishing ecosystem has encountered numerous obstacles. Some big publishers and funders refused to sign up, and the project was delayed for a year to help smaller publishers transition. Last year the European Research Council decided to withdraw its support over Plan S rules that would stop researchers from publishing in journals not judged to be transitioning to an open-access model.

The big commercial publishers Elsevier, Springer-Kluwer and Wiley-Blackwell own more than 40% of all published articles and the majority of the most prestigious and widely-circulated journals. After initial opposition, they and other publishers, have been trying to adjust to the shock of Plan S and are shifting their pay-to-read subscription models towards more open-access content.

Plan S has forced the big publishing houses to come up with “transformative agreements” to help them transition. These are fixed-term contracts negotiated between large publishers and libraries or universities, in which the public institutions pay lump-sum fees for unlimited access to certain journals and their researchers can publish their work openly at no additional cost.

Researchers foot the bill

Yet some publishers’ attempts to recoup funds lost to open-access initiatives may end up hitting the wallets of researchers themselves. Recently, several companies introduced options for researchers to pay fees (APCs) to have their papers published open access in some of their more prestigious journals. Nature Springer, which says it is “committed to joining Plan S”, announced in November that it will charge authors up to €9,500 (CHF10,200) to make their research papers free to read in Nature and 32 other journals. The high price caused sharp reactions in scholarly circles.

The Ferrari version of open-access journals.

— Jochen Markard (@JochenMarkard) November 25, 2020External link

€2'190 non-refundable for submission and €9'500 for its flagship journal. Publisher says high fees are bc of inhouse editors and high numbers of submissions (details below)

https://t.co/ID3RTuEqSBExternal link

Springer Nature argues that its costs are higher than others because Nature-branded journals are highly selective and review many more papers than are published. They also employ many in-house editors and other staff. But critics warn that high APCs risk magnifying inequalities among disciplines, universities and regions.

Transparency on pricing may improve because of Plan S, but it is unclear whether the initiative will drive down publishing costs which can be high for some disciplines.

Beate Fricke, chair of pre-modern art history at the University of Bern, points out that four fees are involved when researchers in her field want to publish. They must buy the images, pay for the right to publish them and pay an article processing charge (APC). Then, libraries have to pay subscription fees for the journals.

“An article has 15-50 images, a book has 200 images and each image costs $300 – do the math,” Fricke says.

In any case, the higher prices charged by some journals are unlikely to deter many researchers who must live by the “publish-or-perish” culture from seeking publication in prestige titles.

“In economics there is a ranking of the best journals and a young researcher doesn’t have the choice between open access or not open access,” said Rafael Lalive, an economics professor at the University of Lausanne.

Swiss observer

Meanwhile, Switzerland has been observing the initiative on the side-lines. The Swiss have voiced support for Plan SExternal link, but did not sign up, partly due to timing. Switzerland has its own national open-access strategy, devised in 2016, which has similar objectives to the initiative. It aims for all scientific publications benefiting from Swiss public funding to be available free of charge by 2024.

Switzerland’s national open access strategy allows scientists to either publish their results in open- access journals or open-access books that are immediately freely accessible. This is the so-called “gold” route.

The other path is to allow researchers to publish their results in a journal with a paywall first, then place them in a public database after six months. Books are subject to an embargo period of 12 months. This is known as the “green” route.

The most popular for SNSF-funded researchers is the gold route (22% in 2018-2019), followed by “hybrid” or subscription journals (17%) and the green route (14%).

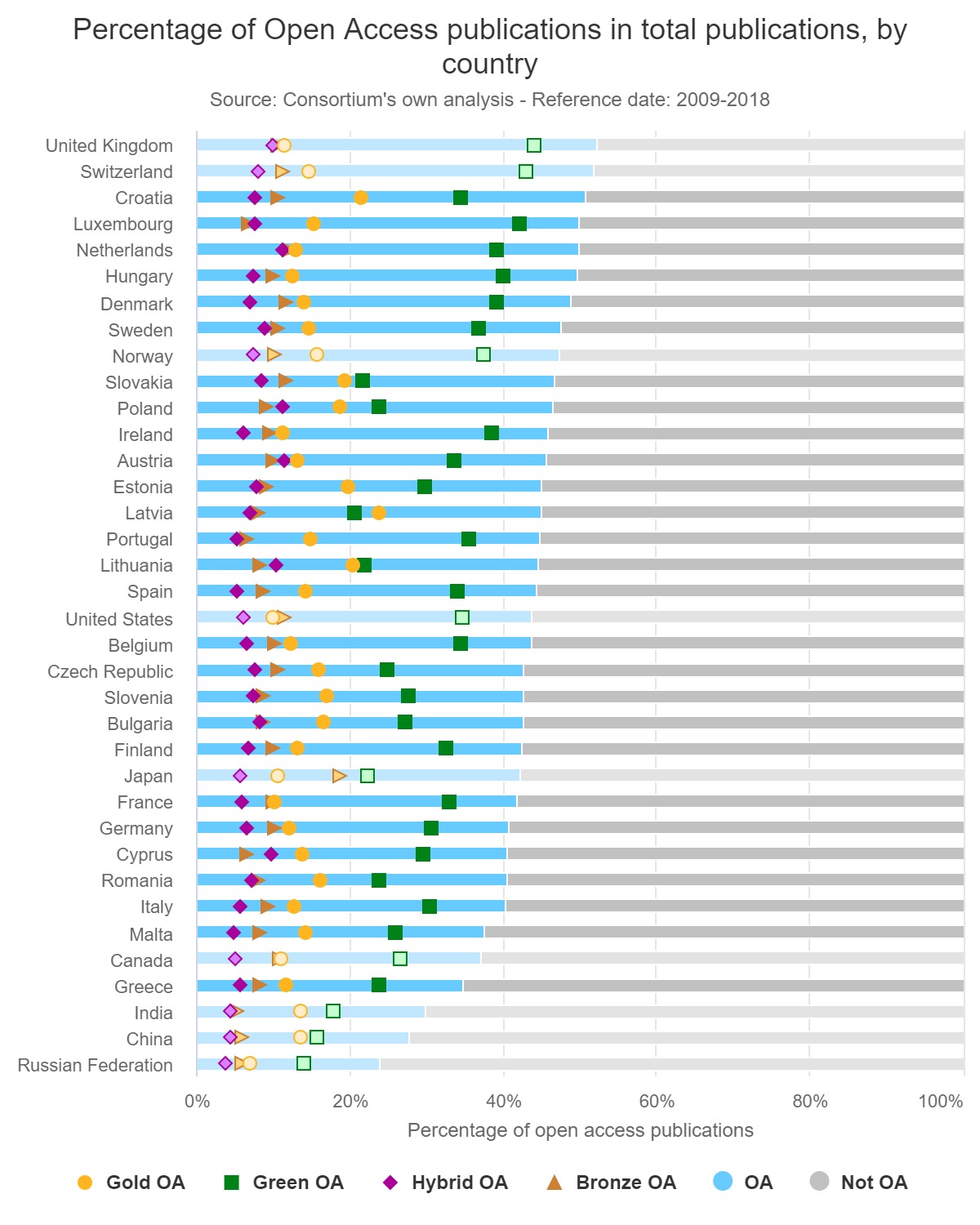

The European Commission ranked Switzerland in second place (51.8%), behind the UK (52.3%), for the percentage of its publications that were open access for the 2009-2018 period. And a separate monitor of publications in Germany, Switzerland and Austria showed that 65% of papers published in Switzerland were open accessExternal link over the past four years, slightly higher than in neighbouring Germany (57%). This makes Switzerland a European leader in the area of open-access publication, which is one reason why the organisers behind Plan S are eager for the Alpine nation to get on board.

[Gold Open Access: research outputs that are publications in an open access journal; Green Open Access: research outputs that are publications in a journal that are also available in an open access repository; Hybrid Open Access: research outputs that are publications in a subscription journal that are open access with a clear license; Bronze Open Access: research outputs that are published in a subscription journal that are open access without a license.]

“We will consider it,” said Tobias Philipp, a scientific officer at the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), noting that Switzerland’s possible Plan S membership will be “up for discussion sometime this year”.

One sticking point for Switzerland has been uncertainty over how Plan S would be implemented. That has become much clearer in the past few years, says Philipp. His organisation, which funds the majority of Swiss scientific research, is watching to see whether the European scientific funding scheme Horizon Europe includes Plan S principles in their requirements for how research is published. If that happens, Philipp says it would be one reason for Switzerland to “seriously reconsider” its position on Plan S.

In the meantime, the umbrella organisation for Swiss higher education institutions, swissuniversities, has signed transformative deals with two of the three largest publishers: Elsevier (CHF15 million) and Springer (CHF13 million). Talks are ongoing with Wiley. The three publishers account for 60% of the articles consulted in Switzerland.

Are such deals, and the emergence of Plan S, a sign that the world of scientific publishing is at a turning point? Markram, whose Frontiers journal was a pioneer in open-access content, says she “will believe it when she sees it”, having predicted a change seven years ago that hasn’t yet come.

“The publishing system is very resistant to change,” she says. “There’s a lot of talk and initiatives about change but the tipping point hasn’t come. It’s a hugely conservative system.”

Swiss research institutions provide around 1.7% (2016 figure) of the annual total number of scientific papers published worldwide, compared to 23% for the United States, 7% for the UK and 6% for Germany. Among Swiss universities, the federal technology institute ETH Zurich publishes the most (16%), followed by the University of Zurich (15%), the University of Geneva (10%) and the University of Bern (10%), together with their respective university hospitals.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!