Swiss researchers want to unravel the mystery of the Pamir glaciers

Some glaciers in Central Asia appear to be unaffected by global warming. Instead of shrinking, their surface area has remained stable or even increased. A Swiss project is investigating the reasons for this anomaly.

The retreat of glaciers is among the most visible effects of rising temperatures. Since 1850, Alpine glaciers have lost about 60% of their volume, profoundly transforming the mountain landscape. Melting is accelerating, and the world’s glaciers are already losing an average of up to 298 billion tons of ice per year.

But there are exceptions. In the Pamir massif in Tajikistan and adjacent mountain ranges in Pakistan, India and China, some glaciers are stable or even growing. This is a unique phenomenon known as the ‘Pamir-Karakoram anomaly’.

“When I saw it, I couldn’t believe it: it’s the only place in the world where you can walk from the ground to the surface of the glacier without passing over a lateral moraine,” Francesca Pellicciotti, a glaciologist at the Swiss Research Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape (WSLExternal link), tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

Ice in all its expressions

The causes and consequences of this glacial anomaly is now the focus of an extensive research project led by the WSL and the University of Fribourg. The interdisciplinary ‘Pamir’ project External linkwas selected by the Swiss Polar Institute (SPI) as one of two flagship initiativesExternal link for the next four years (the other project is in Greenland, see details in the box) and awarded CHF1.5 million.

The results of the project will matter beyond the Pamir glacier. The rivers flowing from glaciers are an important source of drinking water in Central Asia, a region severely affected by climate change and political instability, Pellicciotti explains.

“The Pamir region is incredible: ice is present in all its expressions,” says Pelliccioti.

In addition to the typical white glaciers, there are debris-covered glaciers, known as “black glaciers”, rock glaciers and permafrost, the layer of permanently frozen ground. “We do not know the reason for this multitude. Usually only one type of glacier is observed in a region,” says Pellicciotti, adding that the climate and elevation structures could likely play a role.

More

Why melting glaciers affect us all

The fact that the Pamir is a little known and little explored area fascinates the glaciologist even more. The high mountain regions and plateaus of Tajikistan, a former Soviet republic, were inaccessible for a long time.

Cryospheric science – which deals with all forms of ice except in clouds – changed dramatically at the beginning of the millennium, thanks to the availability of satellite images, before too expensive and inaccessible for scientists, Pellicciotti explains. “For the first time we had a global view of glaciers and an idea of the state of glaciers and snow on a regional scale,” she says. That is when scientists began to discuss the Karakoram anomaly.

The second flagship initiative supported by the Swiss Polar Institute (SPI) aims to study the effects of climate warming on the ecosystems of Greenland’s southwestern fjordsExternal link. The researchers will analyse how melting glaciers and soil erosion impact the nutrient cycle, marine resources, cloud formation and the livelihood of local populations. “We want to understand how the food web and fish stocks might change in the future,” says project coordinator Julia Schmale from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne.

Three hypotheses

There are three hypotheses that could explain why some glaciers in Central Asia remain stable or even grow. The first is a decrease in summer temperatures that cause less melt. This phenomenon has been attributed to a shift of monsoon. The second is an increase in winter and spring precipitations due to changes in the interactions of the monsoon with Western disturbanceExternal link, an extratropical storm originating in the Mediterranean region.

The third hypothesis is related to agricultural practices. Downstream of the Pamir-Karakorum region, in Pakistan, lies one of the largest irrigated areas in the world. It is assumed External linkthat due to high evapotranspiration – the sum of evaporation and plant transpiration – water returns to the atmosphere and is transported back to the high altitudes of the Pamir, where it precipitates as snowfall

For Pellicciotti, this is the most plausible hypothesis: “Simulations with atmospheric models have shown that moist air masses originating in Pakistan end up dumping snow on the Pamir mountains.”

Revitalising glacier research

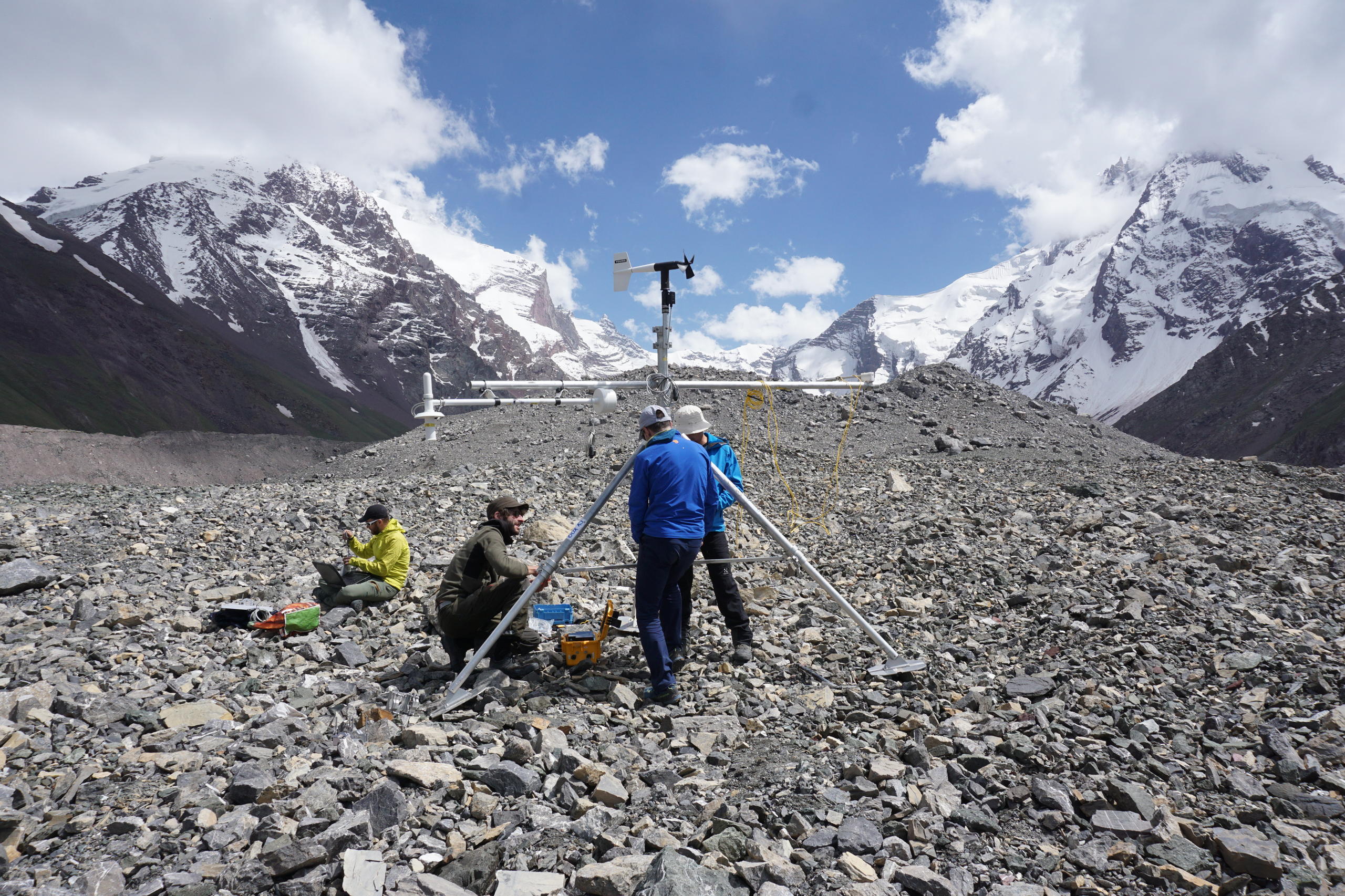

The Pamir project will involve some 60 researchers in Switzerland and Tajikistan. They will study the properties of ice, snow and permafrost and will measure snow accumulation and mass balance of dozens of glaciers with sensor mounted on an airplane. Drilling through the 1,000-metre-thick Fedchenko Glacier, the largest glacier outside the poles, will allow to collect data on the climate of the past.

Another team of the project will reconstruct the history of glacier Soviet research using archives. “Tajikistan has a long history of glacier research, but it stopped with the end of the Soviet Union,” says Abdulhamid Kayumov, director of the Centre for Glacier Research at the Tajik Academy of Sciences.

“Switzerland is known for its expertise in cryosphere research. With its help, we want to relaunch research in our country,” he says.

More

In pursuit of the crystal hunters

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.