Hooliganism in football: Swiss authorities gamble on tough approach

A new strategy by authorities aims to clamp down on violence in football, including via measures such as partial stadium closures. Will it work?

Given that soccer in Switzerland – like in many countries – is used to a certain amount of violence, an incident in Zurich last month didn’t seem initially remarkable. After a scoreless draw between FC Zurich and FC Basel (a game described as “boring” by the Keystone-SDA news agency), 100 Zurich fans faced off with police at a train station near the stadium; stones, fireworks, and flares were thrown.

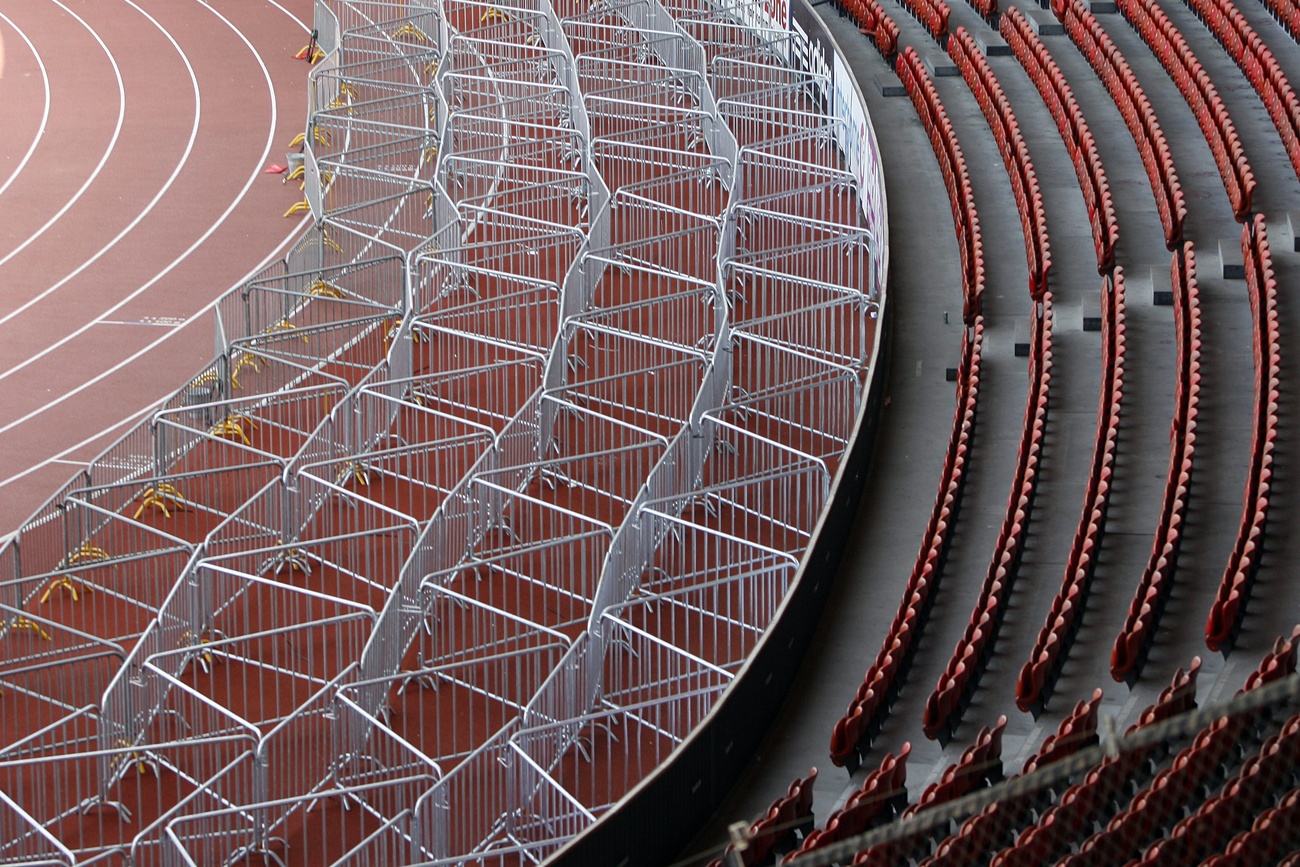

A few days later however, the official reaction showed a newfound intent to clamp down on the hooliganism. Classifying the incident as “serious”, the Conference of Cantonal Justice and Police Directors (an umbrella group for the country’s regional police forces) ruled that, for FC Zurich’s subsequent home match, an entire sector of the stadium would be shut in reprisal. “We don’t want to accept fan violence anymore, and we are taking corresponding measures,” said Conference co-president Karin Kayser-Frutschi.

And so, when FC Lausanne-Sport visited Zurich’s Letzigrund stadium ten days later, the southern stand – where die-hard fans are generally found – was empty.

More

To keep trust, police taught to ‘keep cool’

‘Collective punishment’

The decision, as well as similar ones in recent weeks in Bern, Lausanne, Lucerne and St Gallen, has prompted a volley of media reports and criticism.

Fans in particular are annoyed at the “collective punishment” approach. In the case of FC Zurich, around 4,000 people – including season ticket holders – were deprived of their usual places because of the 100 troublemakers. Giant banners protesting the measures have since been seen in various stadiums, while fans from different clubs – normally sworn enemies – planned a joint demonstration in Bern, before eventually dropping the idea.

Clubs themselves are also unhappy. FC Zurich President Ancillo Canepa argued that last month’s clashes happened a few kilometres from the stadium – beyond our “range of influence”, as he told Swiss public radio SRF. Along with some fans, Canepa has appealed the decision and called for courts to clarify the legality of such measures.

Even politicians have been getting involved: left-wing members of Zurich’s parliament demanded in vain a reversal of the “populist” decision, which they called a “signal of impotence”. Left-wing newspaper WOZ wrote that such hard-line rules were typical of career-conscious “conservative politicians”; one such politician presumably implied, Stephanie Eymann from Basel, said in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung: “why are people angry with the authorities – and not with the hooligans?”

Counterproductive?

Experts on fan violence have for their part reacted cautiously. The University of Bern’s Alain Brechbühl told SRF that such measures could end up being counter-productive, “boosting solidarity among fans, who band together to resist a punishment they deem illegitimate”.

Dirk Baier, a criminality expert from the Zurich University of Applied Sciences, is more circumspect about whether collective measures could make things worse, in the sense of more violent. What they could end up doing, however, is push some annoyed moderate fans away from football altogether – making the sport as such “less attractive”, he tells swissinfo.ch.

As for what works and what doesn’t in stemming fan violence, Baier says reliable data is scarce. But regarding violence prevention generally, he says, “harsh penalties are not a deterrent”. And in the case of football, where violence is a “complex” phenomenon involving a combination of group identity, impulsivity and alcohol/drugs, one-size-fits-all approaches are not the answer.

What would work? Beyond the traditional policework of chasing and prosecuting individual hooligans, Baier says it’s important to focus on the local context: “Zurich needs a different approach to Lucerne or Basel”, he says. “The various actors – police, clubs, fan workers etc. – must discuss the situation together and decide on measures. It takes a coordinated approach from everyone involved, as Germany has managed to do with its ‘stadium alliances’External link”.

Bad behaviour scale

Such stadium clampdowns at a nationwide scale could however be a taste of what’s to come. After years of mitigated efforts (including setting up a database of some 1,000 known hooligans, which was hacked last year), Swiss authorities are currently working on a five-point plan drawn up jointly by the Conference of Police Directors and the football league.

The plan outlinesExternal link various levels of disruption and the corresponding measures they would automatically trigger. For example, level one – dangerous use of fireworks and property damage – would spark a mandatory dialogue between clubs, fans and authorities; level five – repeated physical violence – would condemn a club to play in an empty stadium or to forfeit a game. The closing of stadium sectors is a level three response.

The plan, set to be finalised in March and to be introduced next season, has been met with a mixed response, SRF reported. While clubs largely welcome the clarity of knowing which actions lead to which response, the collective punishment element remains controversial – especially the prospect of forfeiting a game due to the behaviour of a handful of fans, an idea which Baier said could be perceived as “unfair” by supporters – and possibly alienate them further.

The situation elsewhere

Switzerland is not alone in facing hooliganism. The French league has seen problems over the past seasons, with incidents of fans storming pitches to confront players or opposing supporters. Last October, a Lyon-Marseille game was called off after Lyon’s team bus was attacked and coach Fabio Grosso ended up with facial injuries.

In England, disorder also increased after the pandemic, with football-related arrests increasingExternal link by 60% in the 2021-2022 season. According to a reportExternal link in the Guardian, there is “no one explanation” for the rise. However, experts and police interviewed by the newspaper listed pent-up energy and a desire for “carnivalesque” behaviour after the pandemic, as well as increasing cocaine use in and around stadiums, as possible factors. Hooligan incidents had previously been declining for a decade.

That said, with games in England seeing crowds of up to 76,000 in Manchester United’s Old Trafford, antisocial behaviour remains just a small element in the mass of “well-behaved” fans.

And in Switzerland too, while current debates seem to suggest the situation is getting worse, the statistics say otherwise, according to Baier. “In recent years the number of violent incidents has actually been declining,” he says.

So why the crackdown? The issue, Baier says, as with all types of violence, is that “single incidents end up having a very strong influence on perceptions of the problem. They receive wide attention – and a society whose goal it is to prevent all violence then comes under pressure to act to ensure that such outbursts of violence do not occur again.”

Edited by Balz Rigendinger

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.