Tunnelling through a mountain

Constructing an underground tunnel like the Gotthard, which at 57 kilometres long will be the longest worldwide, is a feat of engineering.

The challenges of boring such a rail tunnel, which will witness its final breakthrough on October 15, have been many, and Mother Nature has sometimes made life difficult along the way.

The Gotthard Base Tunnel will be the most important element of the new flat rail link through the Alps. Rising no higher than 550m above sea level, the height of the capital Bern, it will reduce the route from Zurich to Milan by one and a half hours.

“For such a huge project you have to construct from different sites because if you start at one portal and then on the other end, you need 20 or more years for the construction of the entire system,” Heinz Ehrbar, chief construction officer with the contractor AlpTransit, told swissinfo.ch.

“So we have had in total five different main sites which are in the north, Erstfeld and Amsteg, then in the centre, Sedrun and then Faido and Bodio on the other end.”

These five sites have cut the tunnelling time by half. The tunnel is due to open, once it has been fully kitted out, in 2017.

Tunnel vision

The base tunnel is made up of single tubes which are joined every 312 metres with connecting galleries. Trains can change tunnels at the multifunction stations at Sedrun and Faido, which contain ventilation equipment as well as safety and signalling systems.

There are also emergency stop stations every 20km from where people can escape and be evacuated in the event of a fire or accident.

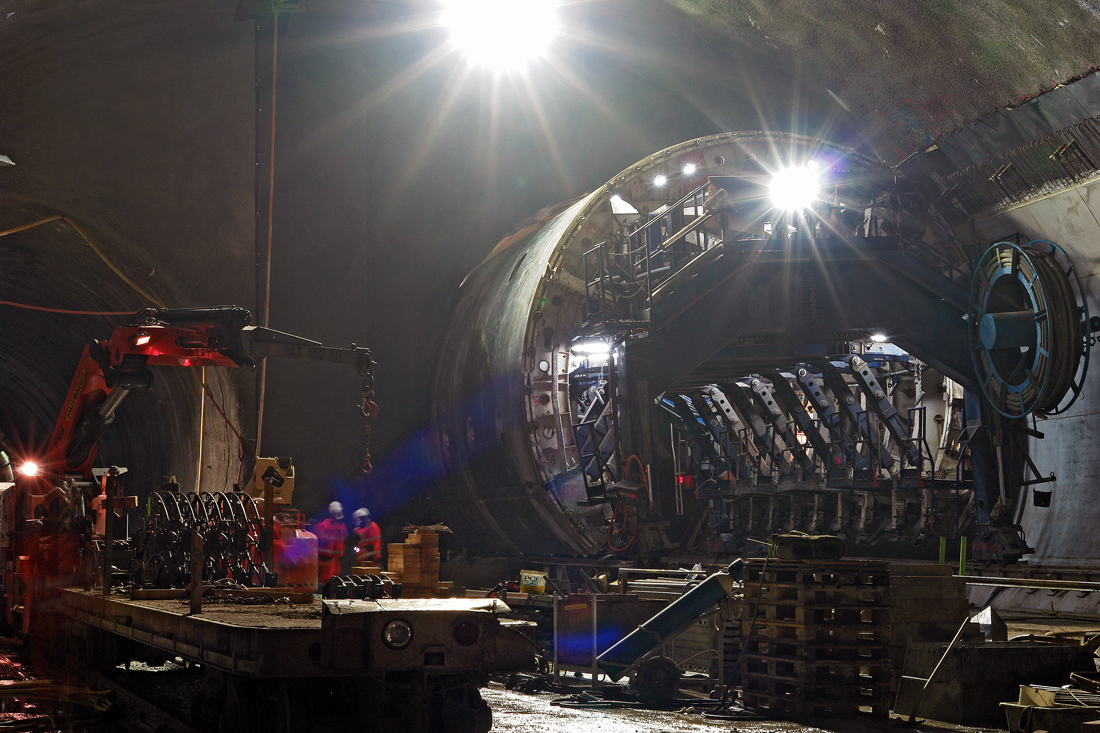

To make the tunnel, drill and blast methods and giant tunnel boring machines (TBMs) have been used, with TBMs doing around 60 per cent of the work.

An estimated 24 million tonnes of rock will have been excavated on completion of the SFr9.74 billion ($9.5 billion) tunnel.

Kalman Kovari, an emeritus professor of tunnelling at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich and consultant to the project, says that tunnelling is not quite as mystical as its reputation. It is simply an engineering activity using natural formations as its material.

No mystery

“Many people think we are exposed to the complete arbitrariness of nature, but this is not correct,” Kovari explained.

Geologists and rock mechanics experts make detailed surveys of the area. The best route is decided and the tunnel is then designed by a group of experts.

Making such a long, large and deep tunnel has presented special challenges. “Many problems arise from depth in particular such as stresses in the rock, possible high water pressure and high temperatures,” Kovari told swissinfo.ch.

The temperature problem was, for example, solved by cooling the 45 degree Celsius air to 28 degrees using a water system, making life more bearable for workers.

Project threat

The Alps’ varied geology – rocks can range from granite hard to butter soft – has also been an issue. “We knew that we would have some very difficult zones to cross with the excavation of the tunnel,” Ehrbar said.

Some people doubted whether the tunnellers would get through the Piora Fault Zone, where initial tests had suggested “running ground”, a granular dolomite mixed with water. Work was put on hold – and the whole project threatened – while engineers debated what to do.

Extra bore holes were ordered which found that the poor quality stratum did not, as feared, extend to the deeper tunnel level. Work was able to resume.

There was also a difficult area just north of Sedrun where the rock was crumbly and subject to severe pressure. This called for thinking outside the box.

Mine technology

Experts used mining technology – a first for an underground tunnel – to solve the problem, which included using steel arches to support the excavation.

But Ehrbar never doubted that the tunnel was feasible. Overall, construction has gone well.

“We are carrying out studies to see if we can open the tunnel a year earlier,” he said.

The final breakthrough, Ehrbar says, will be “very emotional” and a time during which people will remember both the highs and lows of this mammoth project.

For Kovari, the pioneering aspect of the Gotthard Base Tunnel has been its execution and in the openness when dealing with challenges, like at Sedrun.

Pioneering forebears

Kovari would not, however, say that the Swiss are a nation of tunnel construction experts – Britain is too – but the country’s topography has played a role.

“It’s a special ability born out of necessity and continuous activities over almost 150 years,” he said.

The first pioneering tunnels were the Gotthard road tunnel and the Simplon tunnel, where tunnellers faced much more challenging conditions and deaths were commonplace.

The Swiss have honed their skills over the years. But both Kovari and Ehrbar still feel a special admiration for their 19th century forebears.

“The old Gotthard railway tunnel or the existing Simplon tunnel were also the longest of the world of this time,” Ehrbar said. “I think we have to have a big respect for what our great-grandfathers did.”

The Gotthard Base Tunnel (ready 2016-17) and Ceneri Base Tunnel (ready 2019) create an ultramodern flat rail link whose highest point is at 550 metres above sea level. This is much lower than the highest point of the existing route through the mountains at 1,150 metres.

The route through Switzerland becomes flatter and 40km shorter, so faster for passengers. Freight trains travelling on the flat route can be longer and pull up to twice today‘s weight – 4,000 tonnes instead of 2,000 tonnes. They will be up to twice as fast.

These 2 tunnels, plus the Lötschberg base tunnel (opened 2007), are the key elements of the NRLA (New Rail Link through the Alps).

The NRLA is one of the world’s largest construction projects and includes the extension of two North-South railway lines through Switzerland. The total cost is expected to be around SFr18-20 billion (SFr9.74 billion for the Gotthard).

Once the tunnel is in operation, emergency stop stations provide places from where passengers can escape or be evacuated. They don’t have to cross tracks or use lifts. They can then get on an evacuation train.

Should an incident occur, smoke is sucked out of the affected tunnel and fresh air blown into the emergency stop station and through the side tunnels and connecting galleries. A slight overpressure stops smoke entering the escape route to the unaffected tunnel.

If a train stops before the emergency stop station, passengers can use the connecting galleries to escape to the other railway tunnel.

Experts say high-speed rail travel is statistically the safest means of transport. The two tunnels making up the Gotthard Base Tunnel mean no risk of train collision and there are highly sophisticated technical measures to assure safety.

Source: AlpTransit

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.