Two Art Brut exhibitions 40 years apart expose the state of the arts in Cuba

The Art Brut museum in Lausanne recently revisited and revamped a 1983 show dedicated to Cuban artists outside the established art world. Much has changed since then, but the political isolation of the Caribbean island still affects the arts scene.

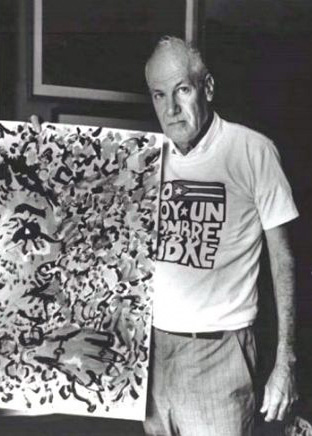

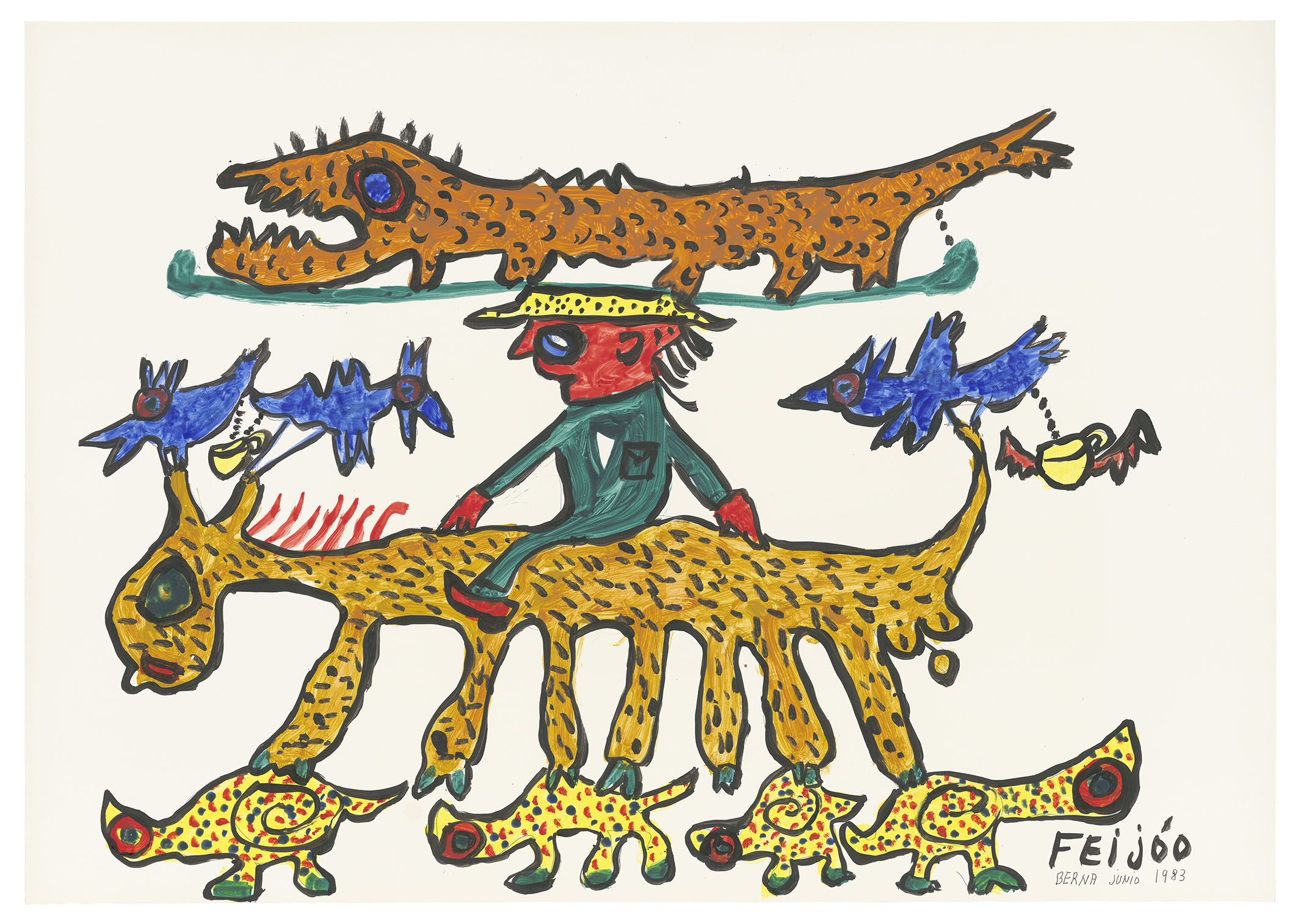

In 1983, the Collection de l’Art BrutExternal link, a small but significant museum in Lausanne, made a lasting contribution to the history of Cuban art. Titled Art Inventif à Cuba (Inventive Art in Cuba), the exhibition featured artworks by some 30 artists from Villa Clara, a provincial town 300km from Havana, collected by Samuel Feijóo (1914-1992), one of the most remarkable personalities in the Cuban arts scene of the 20th century, though almost forgotten today.

A writer, poet, publisher, ethnologist, painter, self-taught draughtsman, and in later years adviser to the culture ministry, Feijóo left Havana and the established artistic circuit even before the Cuban Revolution of 1958 to seek art and artists among the simple folk.

His quest was to find creativity that “should emanate in an original form, replete with wisdom, far removed from imitations and confining conventions”, as he wrote to the French artist Jean Dubuffet, the leading initiator of Art Brut.

In a friendship nurtured in a decades-long correspondence, Feijóo and Dubuffet shared a complicity that eventually led to the 1983 show. It also echoed loudly in the exhibition Art Brut Cuba, which ran from December 2024 to April 2025, drawing considerable critical acclaim and more than 12,500 visitors.

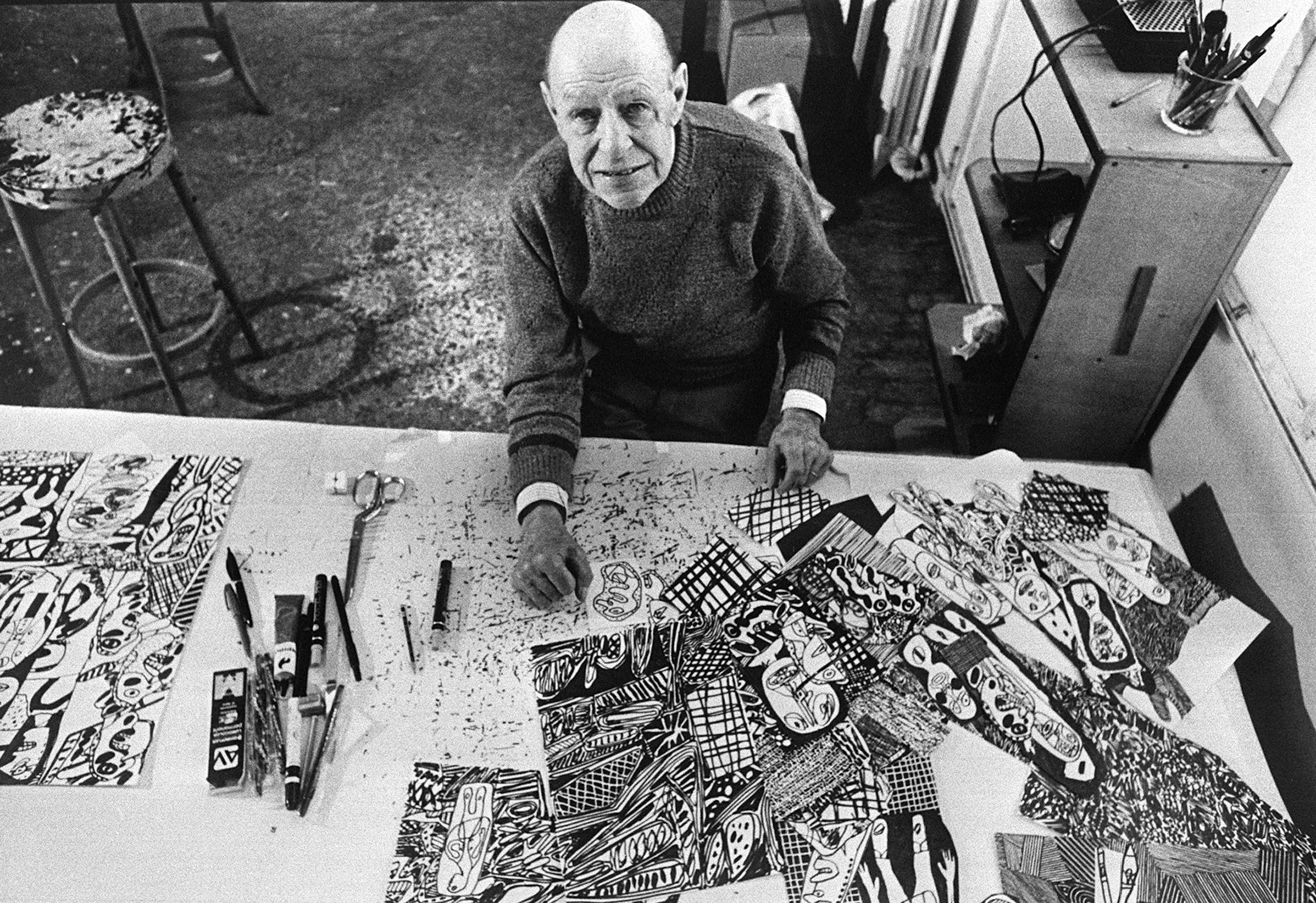

When the French painter Jean Dubuffet laid the foundations for what would be called Art Brut, or Outsider Art in English, his starting point was that simple people, psychiatry patients, prison inmates and anyone making art outside the world of galleries, museums and academies was capable of more poetry than established art circuits.

From the late 1940s until his death in 1985, Dubuffet collected artworks from marginal painters and sculptors around the world. Unable to find a proper place to store it in France, he donated the collection to the city of Lausanne in 1971, which in turn created a museum for it, the Collection de l’Art Brut.

Where every artist is an island

It’s not just living on an island that makes Cuban artists among the most isolated in the world. Since 1958, the country has endured the longest trade embargo in modern history, imposed by the United States and still in force.

The economic and social impacts of the embargo are evident in all aspects of ordinary life; for artists, daily grievances add to a rigidly state-controlled environment, which, according to Sarah Lombardi, the curator of Art Brut Cuba, “makes it more difficult in Cuba than elsewhere to depart from collective norms and establish artistic individuality”.

However, as Lombardi points out in her introduction to the show’s catalogue, all these factors “make this island a fertile environment for the production of creations unaffected by outside influences” – more in line with the basic principles of Art Brut.

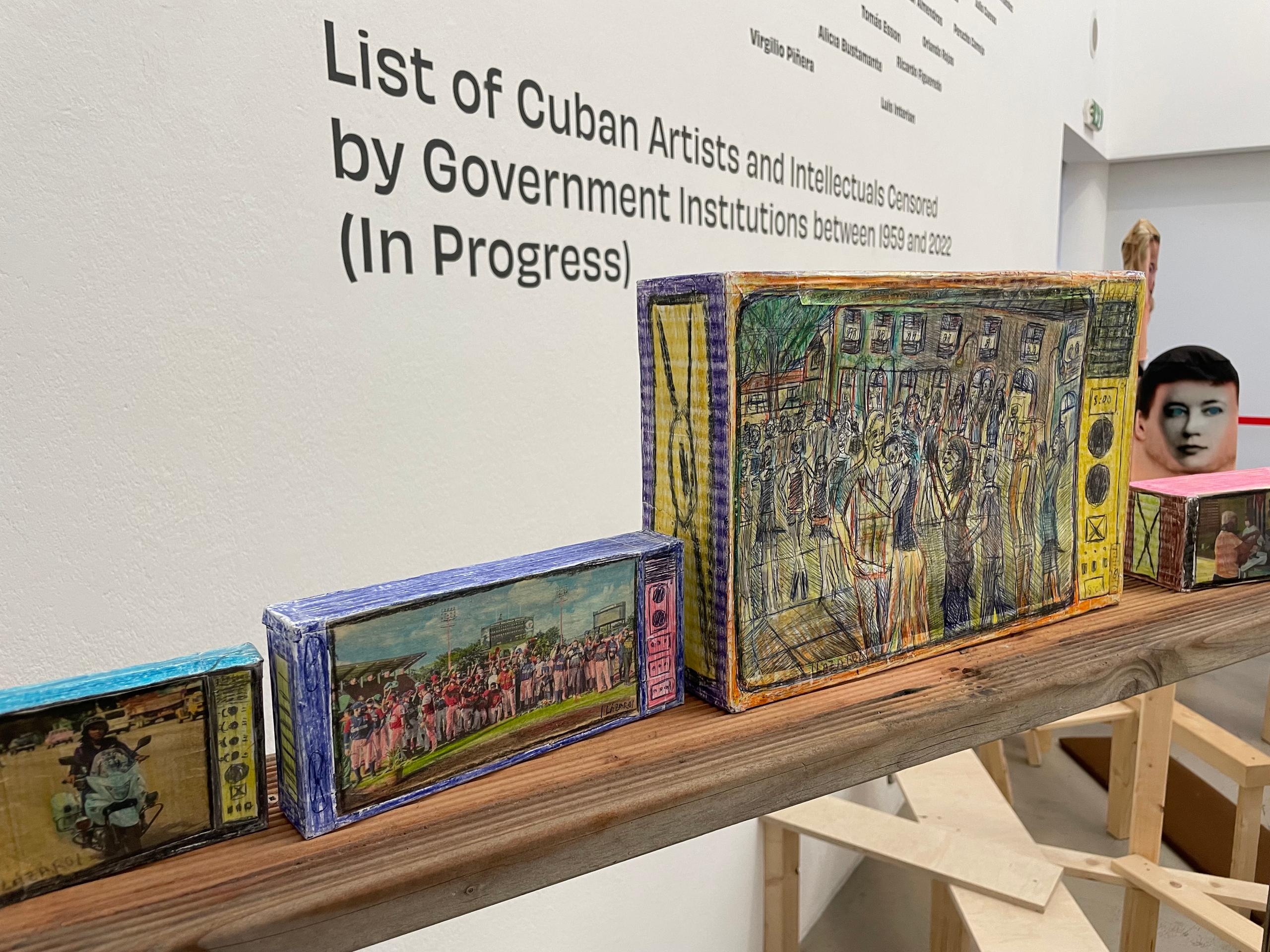

For the revamped exhibition, Lombardi brought to Lausanne works created in the 41-year gap by the artists of the 1983 show, together with a younger generation supported by Riera StudioExternal link, a rare independent art centre-cum-gallery in Havana, named after its founder, the artist and promoter Samuel Riera Méndez.

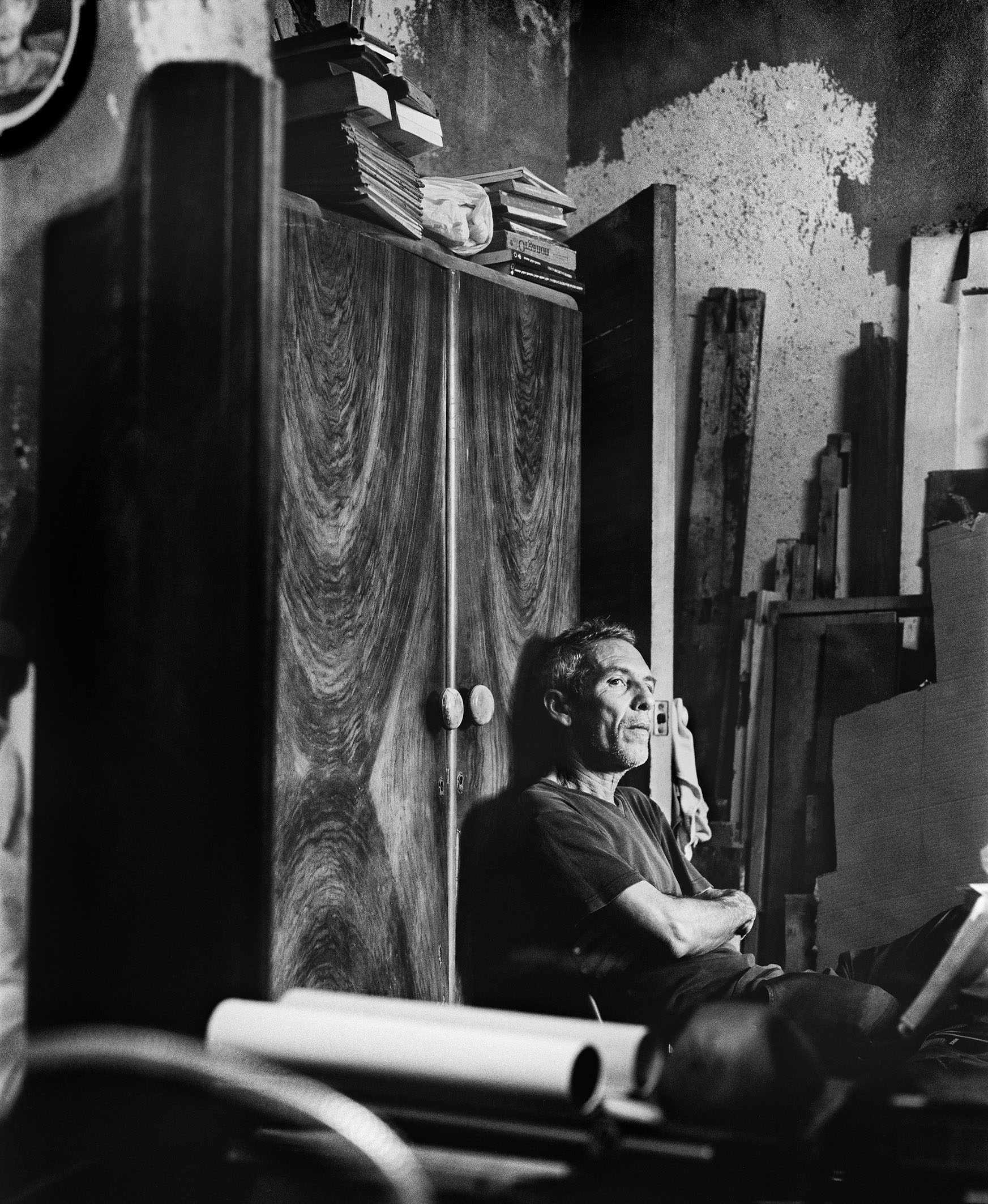

For Art Brut Cuba, Sarah Lombardi also commissioned two photographers and videomakers, Lorenzo Valmontone and Thomas Szczepanski, to document the lives and works of four Cuban artists: Miguel Ramón Morales Díaz, Josvedy Jove Junco, Federico García Cortízas, and Damián Valdés Dilla.

The pictures and accompanying video, titled “Vagabond Souls” (Les Âmes Vagabondes), constitute a parallel show that plunges the visitor into the ordinary reality of these artists and their surroundings.

In an interview with SWI swissinfo.ch, Lombardi stresses that “work and life are mixed for everyone, for every artist, but in Art Brut in particular, there is no separation between the place where people live and the place where they create. The notion of artist doesn’t exist for them. Their creations happen on a day-to-day basis”.

A tale of two Samuels

Comparing the two exhibitions, the differences are more striking than their similarities. The Riera Studio, in its principles, is a direct heir of Samuel Feijóo’s endeavours and is strongly influenced by Dubuffet’s credo, focusing on art made by vulnerable social groups or individuals outside established official art institutions or mainstream art platforms. But however close in theory, the material realities of Feijóo’s and Riera’s art are radically different.

Feijóo’s artists belonged to a relatively close, though marginal, group, united around his publication Islas, that ran from 1959 until 1968, when the group became known as Signos (1969-1985), with its own publication named Signos, too. According to Dubuffet’s “dogmas”, Art Brut is quintessentially individual, reflecting the artist’s particular vision in their social isolation – therefore art groups, movements or collectives are out of the question.

“These artists from the Signos group had a high profile within Cuba,” Lombardi says. “That’s not at all the case with the contemporary Art Brut artists I’m presenting now, who are attached to the Riera Studio and who have absolutely no visibility in Cuba.”

The 1983 show was supported by the Cuban state, while the recent one had no official support. This reflects the different stances of Feijóo and Riera in relation to the government.

Samuel Feijóo enjoyed the approval of the Cuban authorities, who did not control his publications. He worked at a state university in Villa Clara and developed close ties to the culture ministry. “Since he was financed by the state, he was able to present his artists in official venues, and even in galleries and exhibition projects abroad,” Lombardi says.

Riera Studio is, at best, tolerated by the government. It receives no official funding and finances its activities through modest sales to foreign collectors and tourists.

Following Dubuffet’s example, Feijóo donated his collection to the Cuban state in 1982. When the idea of making an exhibition in Switzerland arose, the works were already in the hands of the government, so the state had to be involved for the show to happen. The Cuban authorities demanded control over the choice of works, but that was no hurdle, thanks to Feijóo’s good contacts. The Cuban ambassador even went to the airport to help when the artworks arrived in Switzerland.

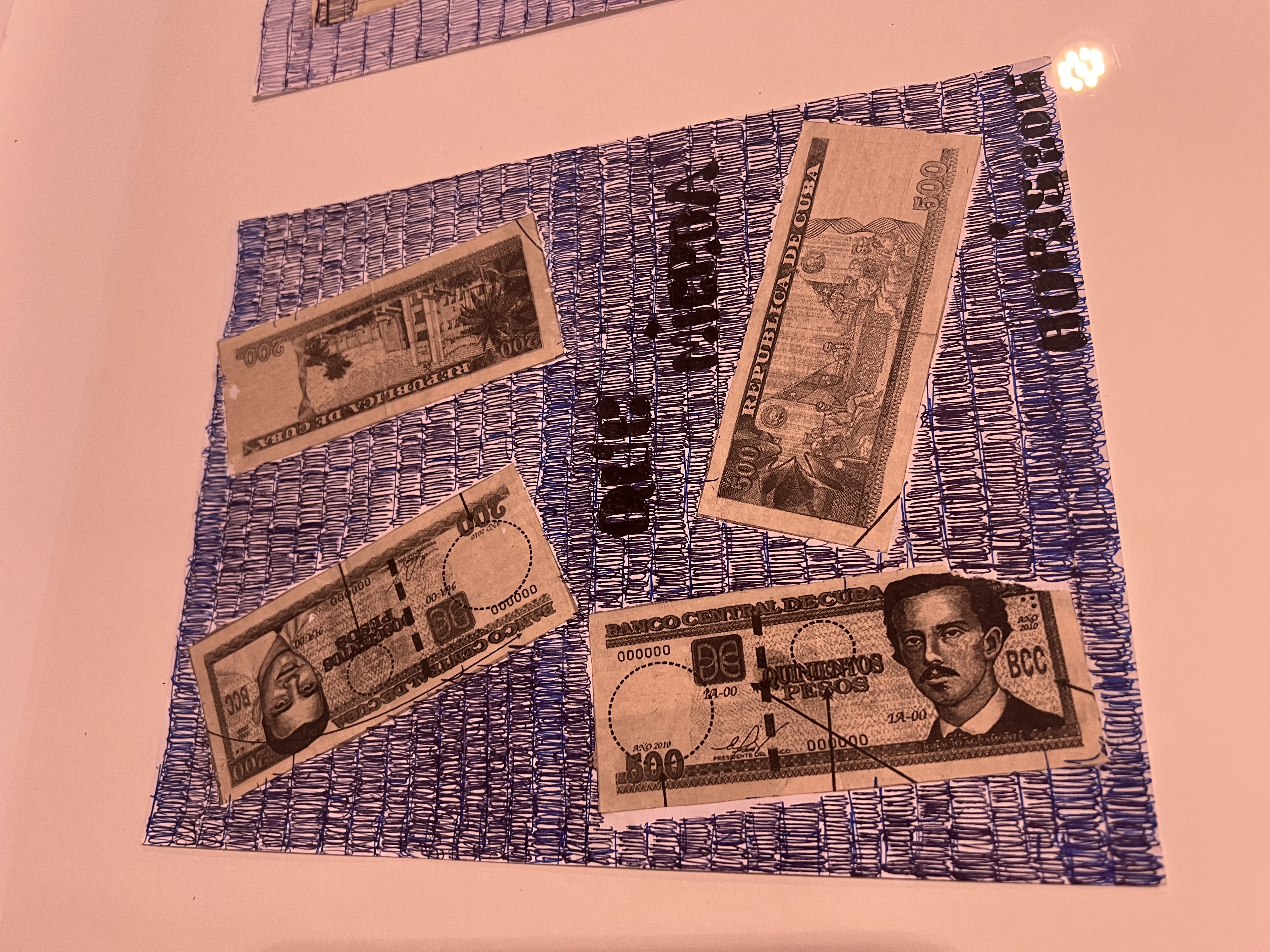

>> A long landscape by Damián Valdés Dilla, on display at Art Brut Cuba:

Marginal, not dissident

Lombardi notes that among the contemporary artists she presented, the only one who has a critical, political discourse is Boris Adolfo Martin Santamaría. “And yet we can’t call him a dissident artist,” she says. “Even though he’s critical of Cuban politics, of Fidel [Castro], of Raúl [Castro] and so on, he’s an outsider, he’s homeless; he started creating when he discovered he had AIDS.”

“Dissident artists possess a critical voice that goes beyond themselves,” Lombardi says. “There’s a risk that they will be heard by the public, and so they become a threat. And often they leave the country because they risk imprisonment or other threats. In Boris’s case, he’s a complete outsider, so nobody hears what he has to say.”

Still, some of these apolitical artists may find themselves entangled with dissident circles, as happened in the Cuban section of the latest documenta 15 grand exhibition in Kassel, Germany, in 2022. Presented as a collective organised by the exiled artist Tania Bruguera, in which the individual names of the artists were effaced, it brought to an international viewership a large display of works by, among a few other Riera Studio artists, Lázaro Antonio Martínez Durán, whose practice is a way to communicate with the outside world and to overcome his intellectual disability.

Market awes and woes

Durán is today a rare case of an Art Brut Cuban artist represented by an international gallery, which is an achievement considering the small space for Art Brut in the billion-dollar global art business.

Lombardi says the Art Brut market is constantly expanding, however slowly and modestly, with an increasing circuit of collectors. Some artists from the Dubuffet original collection have even become blue chips, such as the Swiss Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930), whose large-format works can fetch up to CHF300,000 ($365,000). But prices for artworks by the contemporary Cubans of the Riera Studio vary between CHF1,000 and CHF5,000, and seldom surpass that.

Meanwhile, Feijóo’s collection has simply vanished, Lombardi says. “It was poorly preserved, or stored in inadequate places, and not only the collection but also Feijóo’s archives disappeared.”

Just like Feijóo himself. “For the younger generation in Cuba, Samuel Feijóo, notwithstanding his past fame as a reference throughout Cuba and Latin America, is a name that has all but disappeared.”

Edited by Catherine Hickley/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.