How anti-Semitism fuelled early opposition to department stores

Roughly half of all department stores in Switzerland were founded by Jewish immigrants. In the 1930s anti-Semitic agitation against them escalated, with the federal government even forbidding the construction of further department stores.

On February 21, 1937, over 4,000 angry tradespeople in Lausanne met to oppose a discount department store called Epa. This store – Epa was an abbreviation for “all one price” in German – was ruining small businesses, they said, and the government needed to intervene. As they pointed out, it was ruined small-business proprietors who had brought Adolf Hitler to power in Germany.

In this era of Depression, Epa’s low prices were a hit with working families and the unemployed. Yet its discount policy simply fanned the flames of the already intense feelings of hostility that some struggling shopkeepers held toward the department store.

In Switzerland, anti-Semitic prejudices repeatedly rise to the surface. An example is the discussions 25 years ago about the dormant assets of Jewish Holocaust victims, Nazi gold in Swiss banks and Swiss refugee policy during the Second World War, which was characterised by a fear of “Judaisation”.

While the government of the day reluctantly agreed to pay compensation for the lost assets, almost half of the Swiss population wanted to reject all claims, according to a poll by the public broadcaster, SRF. Anti-Semitic stereotypes were regularly used as arguments in letters to newspapers. The Federal Commission on Racism noted a total lack of inhibition when it came to making anti-Semitic statements.

Where did these ideas come from? In a four-part series, SWI swissinfo.ch explores the role anti-Semitism played in Switzerland before, during and after the Second World War.

Among all its competitors, Epa was singled out for criticism. Neither the establishment of cooperative retail chains nor that of other department stores aroused such hostility as the appearance of Epa (which came to be known as Uniprix in French).

The disquieting aspect of this animosity was that the Swiss owners of Epa were the Jewish retail businessmen Julius Brann and Maus Frères SA. In 1930 they had opened the first three Epa stores in Zurich, Geneva and Lausanne.

Anti-Semitism as a reaction against modernity

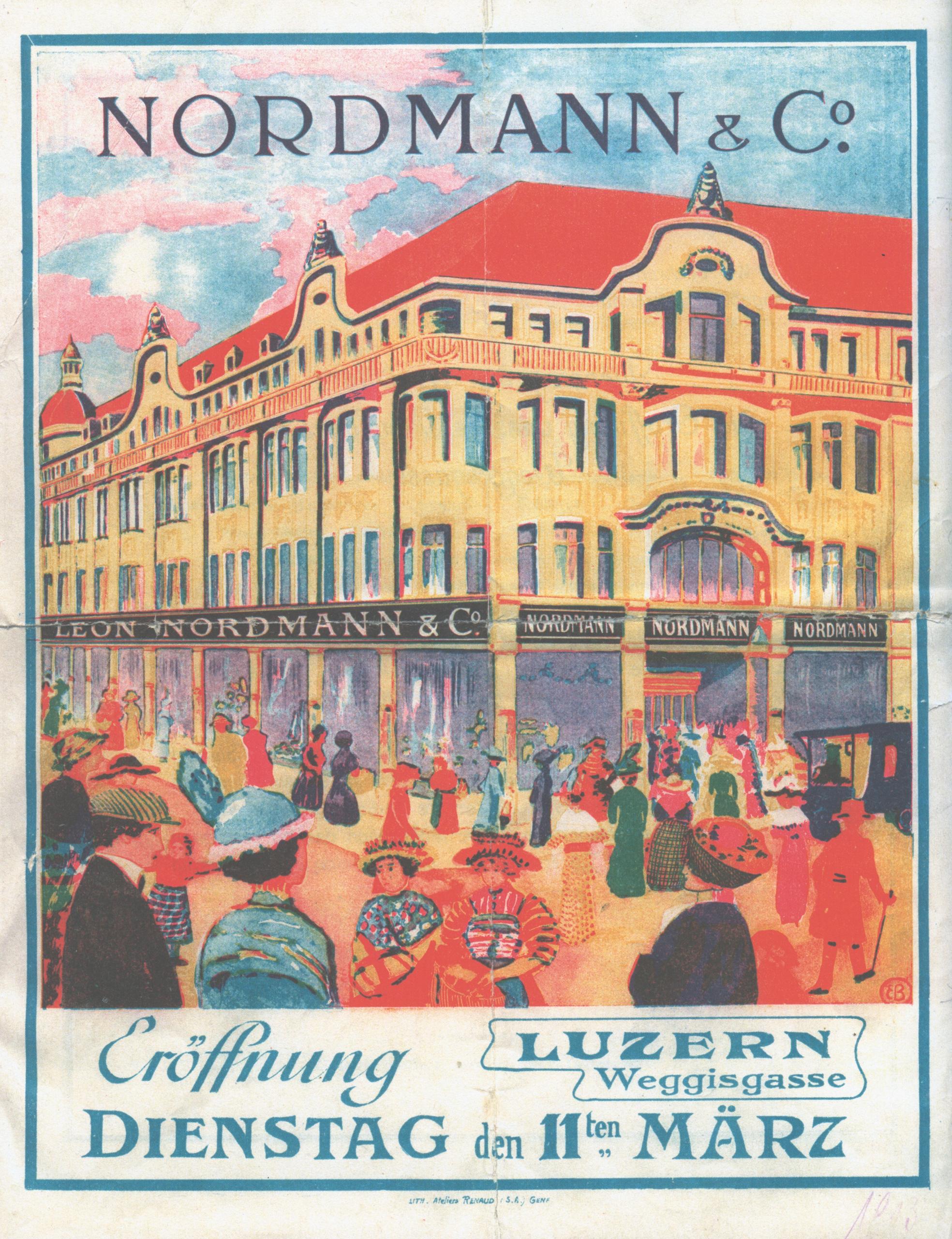

Brann hailed from the town of Rawicz (in what is now Poland). In 1896 he opened Switzerland’s very first department store, in Zurich. The Maus and Nordmann families originally came from Alsace. They settled first in Biel, before they opened their first jointly-owned department store in Lucerne in 1902, which was called Léon Nordmann.

Then David Loeb, a travelling market vendor who hailed from Freiburg im Breisgau, set up the Loeb department store in Bern, which exists to this day.

Most of the pioneers of the Swiss department store business at the beginning of the 20th century came from neighbouring countries. Many were Jews who had immigrated from what was then West or East Prussia, or else from Alsace.

Already at the turn of the century, small-time shopkeepers were fiercely resisting the rise of such large retailers in Switzerland. Department stores were condemned as “giant businesses” or “monster markets” and “a harm to the economy”.

The trend of mass consumption offended the system of moral values held by many people at the time. Department stores with all their products on offer were seen as a “great social hazard” that would cause “a great deal of mischief”, as listeners heard in a 1901 speech in Zurich.

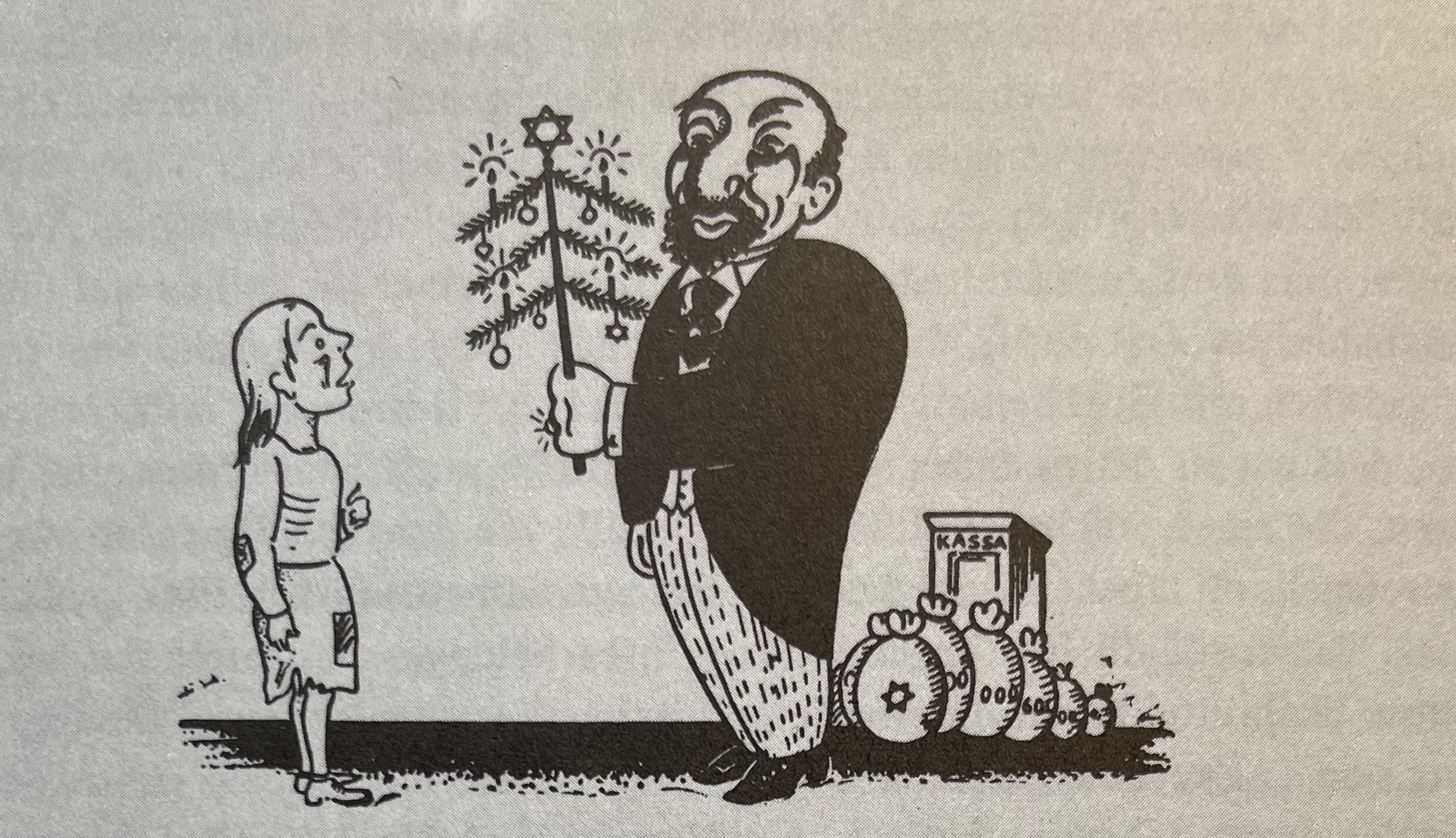

Modern business strategies like advertising were pilloried not only as “dishonest” and “unreal”, but also as specifically “Jewish” approaches to doing business. Anti-Semitism was never far away from the arguments of these critics.

In the city of Biel in canton Bern, there was already strong resistance by 1902 to the department stores of Knopf and Brann. Both these department stores were owned by Jews. The then secretary of the lobby group representing shopkeepers and tradesmen in Biel led a campaign with moralistic overtones against the two “Jewish” department stores. They represented “cultural degeneracy” and were a “product of mean-spirited money-grubbing”. In comparison with the Paris department stores, they were “just selling cheap junk”.

The anti-Semitism that was mixed in with the criticism of the department store was also a critique of capitalist modernity. The department store seemed to critics such as the German “spokesman for small business”, Paul Dehn, in 1899, to stand for “deception and swindling” and “greedy capitalist speculation”.

Jews were denounced as the main purveyors of this change. The critics reduced them to a class of traders distinguished by greed and a lack of scruple. They were undermining traditional ideas of commerce and traditional society in general.

Federal government ban

After an interval of relative quiet, the attacks on department stores flared up again in the 1930s. In April 1933, department stores in Baden were defaced with swastikas. In May there were incidents in Zurich in which the display windows of some department stores were defaced with swastikas and slogans like “Don’t buy from Jews!” and “Filthy Jewish swine!”.

The Swiss National Front movement took over the ideological programme of the Nazi party in Germany, which had already begun targeting department stores. Apart from industry pioneers Rudolph Karstadt and Theodor Althoff, the German department store operators were all Jews belonging to families that had settled in the borderlands of Prussia several generations before.

After Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, this whole business sector was systematically destroyed by means of dispossession, looting, and eventually the deportation and murder of the Jews.

In Switzerland, meanwhile, National Front slogans and ideology made sense to struggling small-time shopkeepers following the Depression. New Switzerland, a chauvinistic small-business group that was close to the National Front movement, demanded a ban on any further building or expansion of department stores, discount stores and chain stores until 1945 – and scored a victory. In October 1933 this proposal was urgently endorsed by the government and passed with a large majority in parliament.

‘Jewish mega-capitalists’

In spite of these restrictions, things just got worse. Venomous slogans and polemics stirred up the small-business owners more and more against Epa. This was a danger to social peace in Switzerland, said the Journal de Genève in 1937. The department store was a foreign idea with international capital and anti-social methods. Its rapid growth had driven native-born retailers into misery and anarchy. For small business, this was a matter of life and death.

Officially, the organisers of this campaign in French-speaking Switzerland denied all charges of anti-Semitism. The committee’s president stated in the Gazette de Lausanne dated February 22, 1937 that the call to close down Epa was not anti-Semitic, but “anti-parasitic”. At the same time, he said he would fight with all means in his power against these “foreign” or “recently naturalised” Jewish mega-capitalists, who ruled the discount store sector in Switzerland.

In that troubled year of 1937, the campaign went so far as to call upon Julius Brann and Maus Frères to wind up Epa and to emigrate. The Epa owners were referred to as “monsters” and “sharks”.

Sale and emigration

The events of the 1930s were not without their effects on the Jewish department store owners. The childless Julius Brann sold the companies he had built up, Brann AG and Epa, to his long-time chairman of the board, Oscar Weber, and emigrated to the United States.

The Jelmoli department store had been founded by the Italian businessman Giovanni Pietro Jelmoli, and it is still in business today. Yet in 1940 all Jewish board members and executive managers quit their positions and left for the US as well.

The owners of Maus Frères, on the other hand, managed to acquire the American department store Bergner’s in 1938, in an effort to diversify their business. This same strategy was followed by many business owners here, both Jewish and non-Jewish, such as the pharmaceutical conglomerate Roche, which opened an American head office in Nutley, New Jersey.

The Swiss government, which had been driven to its decision on department stores in 1933 by anti-Semitic pressure, actually emulated the threatened businessmen later on during the Cold War. It concluded treaties with Canada and Australia which, in time of war, would enable Swiss firms to transfer their operations to those countries while remaining under Swiss jurisdiction.

Angela Bhend is a historian and author of a book on the Jewish founders of Swiss department stores, Triumph der ModerneExternal link (in German), published in 2021.

- Lerner, Paul: Circulation and Representation: Jews, Department Stores and Cosmopolitan Consumption in Germany, ca. 1880s–1930s. In: Weiss-Sussex, Godela; Zitzlsperger, Ulrike (Hg.): The Berlin Department Store. History and Discourse, Frankfurt a. M. 2013, S. 93–115.

- Briesen, Detlef: Warenhaus, Massenkonsum und Sozialmoral. Zur Geschichte der Konsumkritik im 20. Jahrhundert. Frankfurt a. M. 2001

- Reich, David: Direkte Demokratie in der Krise. Die Funktion des Notrechts in der Schweiz während Weltwirtschaftskrise und Zweitem Weltkrieg dargestellt am Beispiel des Warenhausbeschlusses 1933–1945. Basel 2007

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.