When a US bomber crashed into Max Huber’s Zurich castle

On July 19, 1944, a stricken American bomber crashed into Wyden Castle near Ossingen, the home of Max Huber, professor of international law at Zurich University and president of the Red Cross.

On July 19, 1944, a warm summer day at Ossingen near Andelfingen in the canton of Zurich, five-year-old Ueli Huber was playing in the grounds of Wyden Castle. His brother Ruedi, just one year old, crawled beside him through the tall grass. The children’s idyll came to an abrupt end shortly before midday when an American bomber crashed into the tower and residential quarters of the castle, instantly setting them alight. The building belonged to Max Huber, a renowned professor of international law.

Swissinfo regularly publishes articles from the Swiss National Museum’s blog External linkdedicated to historical topics. The articles are always written in German, usually also in French and English.

The castle’s owner was away from home at the time, spending a few days in the mountains above Lake Geneva for the sake of his health. However, some members of his family stayed at the castle. Max Huber’s grandson Ueli still has vivid memories of this terrifying moment today. A wing of the plane, shorn from the fuselage, came to rest hanging in the very tree under which he was playing, its fuel tanks still burning.

“I was aware of the terrible noise and the commotion as the fire brigade and soldiers ran around all over the place. Understandably, I took fright and ran off. I was halfway to the village of Ossingen before some strangers stopped me and took me into their home.”

Miraculously, no one was killed when the plane crashed at Ossingen. One member of the household staff was slightly injured in the fire, but everyone else remain unharmed. Nevertheless, Ueli Huber was left traumatised by the event. Images of the burning aircraft would haunt him for years to come.

A weekly newspaper reported the calamitous episode in some detail: “On 19 July, around noon, an apparently pilotless American Liberator bomber roared over the Stammheim valley, jets of red hot flame shooting out from one of its engines. The mighty plane suddenly flipped over and began practically nosediving straight towards Wyden Castle. The burning aircraft smashed into the tower; the fuselage came to rest on the chapel roof, one of the wings flew into the overhanging trees, and the cockpit, together with the other wing and a section of the landing gear, was hurled with extreme force into the façade opposite. The entire castle, drenched in flowing oil and gasoline, immediately burst into bright flames.”

The aircraft that crashed into the castle was an American B-24 Liberator bomber nicknamed ‘Jackpine Joe’. It would normally have had a crew of ten on board. As well as carrying bombs, B-24 airplanes were fitted out with an array of defensive guns to be used in the event of aerial attacks by enemy fighter planes. Hence the need for a large crew.

A detailed history of the B-24 ‘Jackpine Joe’ bomber – and those who flew it – is available online hereExternal link.

The ‘Jackpine Joe’ had suffered engine damage during its bombing mission over Munich before then being hit by flak over Friedrichshafen. The pilot decided to steer the bomber towards Switzerland. However, the navigator bailed out of the plane before it reached the border and was taken prisoner by the Germans. The copilot was killed when his parachute failed to open. The other crew members were able to make their way to safety and spent the rest of the war interned in Switzerland.

The US government compensated the Huber family for the damage after the war. Unfortunately, the professor’s own private library had been destroyed when the castle caught fire, and many personal documents had been lost along with it. The firefighters who had rushed to the scene were able to save nothing more than a few valuable pictures.

The bomber that fell from the sky above Ossingen was not the only plane to meet this particular fate: during the war, some 250 aircraft ‒ both Allied and Axis, although the latter in much smaller numbers ‒ crashed in Switzerland or were forced to make emergency landings there. The crews were interned under international law and the planes impounded. The majority of confiscated aircraft were subsequently sent to the airfield at Dübendorf near Zurich, where they were held as part of a huge store.

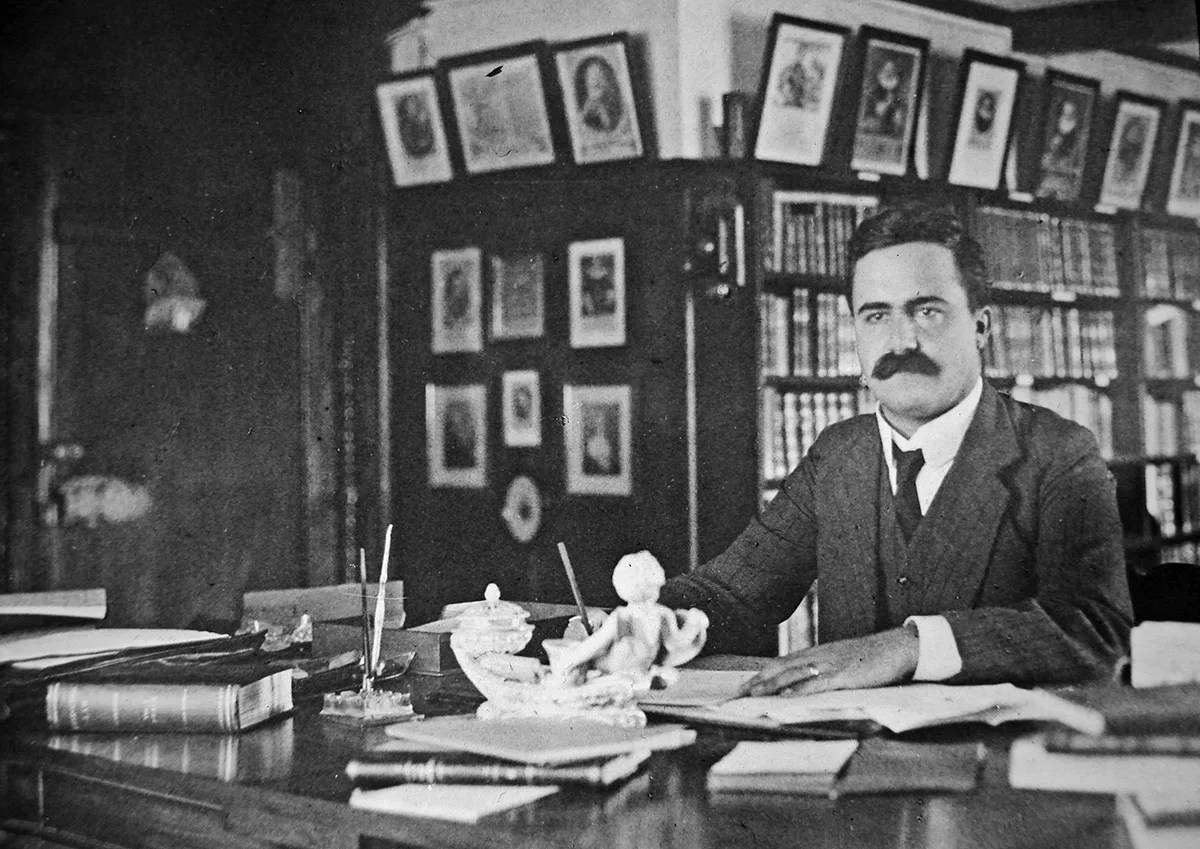

Max Huber (1874-1960) was one of the most renowned personages of his day. He served as the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) from 1928 to 1944, accepting the Nobel Peace Prize on the ICRCExternal link ’s behalf that year. He was also a member and president of the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague and a consultant to the Federal Political Department, as the Swiss department of foreign affairs was then known. Huber was awarded a total of 11 honorary doctorates, both in Switzerland and abroad, in recognition of his efforts as an idealist who had devoted his life to advocating for the victims of conflict.

It should therefore come as no surprise that Max Huber was unperturbed when news of the disaster at Ossingen reached him in western Switzerland. He was simply overjoyed that there had been no loss of life. The 69-year-old spent most of the Second World War living in Geneva, partly because his presence as ICRC President was frequently required there. But he also paid regular visits to the sanatorium on Mont Pèlerin above Vevey to restore his ailing health.

Max Huber shrugged off the loss of his entire library and manuscripts. He later said that it was not the fire at Wyden that caused him the most pain, but the destruction of the Abbey of Monte Cassino, situated between Rome and Naples, by the US Air Force in February 1944. That was where Benedict of Nursia, the founder of the Benedictine Order, had composed the Rule of Saint Benedict in 529 CE. It contains the famous phrase ora et labora (“pray and work”), expressing the link between spirituality and work that had been a leitmotif for Max Huber throughout his life.

Dominik Landwehr is a cultural and media scientist and lives in Winterthur.

The original article on the Swiss National Museum’s websiteExternal link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.