As Switzerland prepares to chair the OSCE, is this body still relevant?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is one of several challenges facing the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Hopes are high that Switzerland’s upcoming chairmanship can help reset dynamics with Moscow.

What is the OSCE?

The OSCE is a forum for dialogue and the largest regional security organisation in the world.

Its greatest strength, but also weakness, is the principle of consensus. A decision can only be adopted if everyone agrees, or at least refrains from placing a veto.

The 57 participating states span much of the Northern Hemisphere. They encompass not just Europe, but also North America and Central Asia.

How and why was the OSCE created?

The OSCE has existed for 30 years, since January 1, 1995, when it replaced its predecessor organisation, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE).

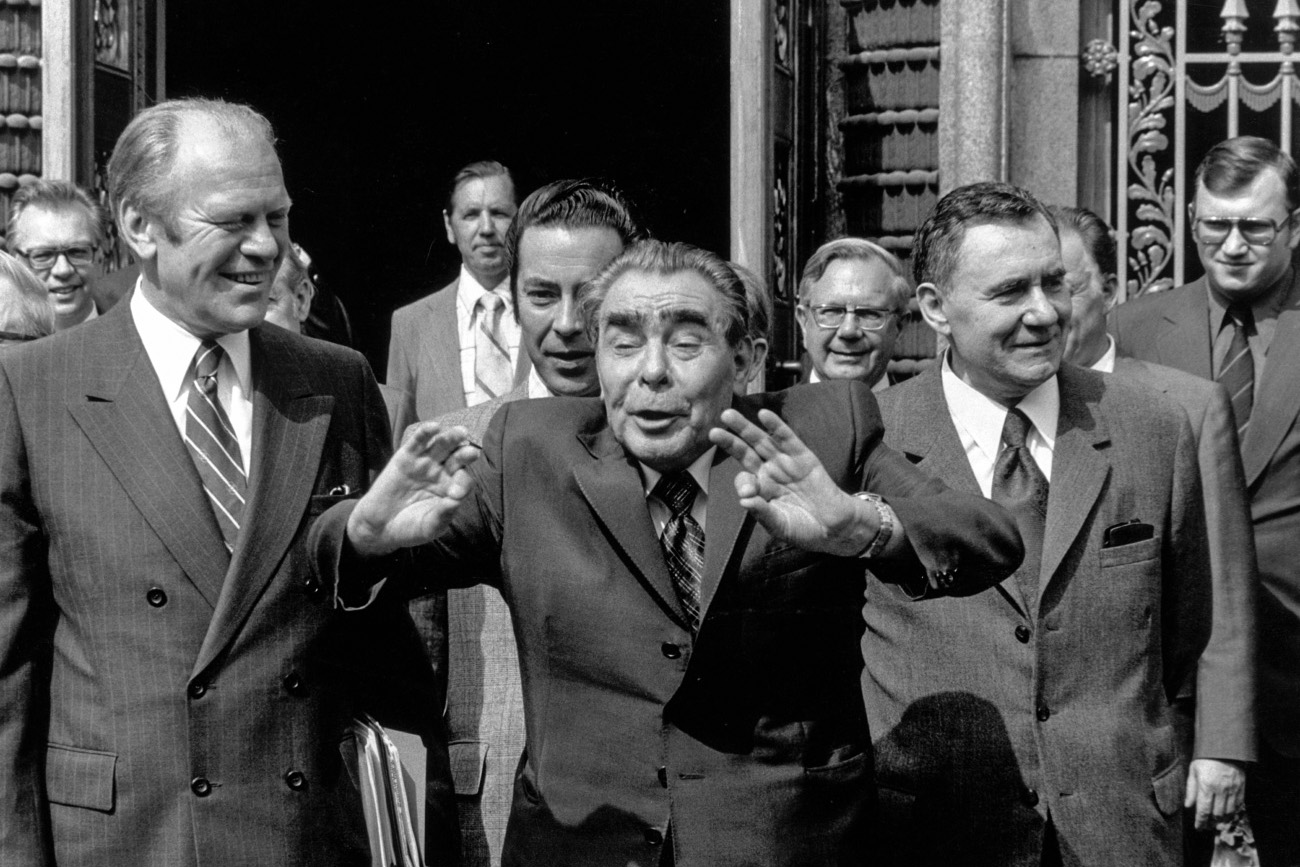

It all began during the Cold War. On August 1, 1975, in the Finnish capital of Helsinki, 33 European countries – along with the United States and Canada – agreed to respect state sovereignty, borders, and human rights. The agreement, later known as the Helsinki Final Act, was the result of two years of negotiations in Geneva over these fundamental principles.

The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, was a historic turning point. In 1990, the CSCE drafted the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, with the hope that the era of confrontation between East and West had ended.

One of the basic pledges in this charter was the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, which it termed the “first responsibility of governments”. The text also laid down that democracy was the only possible system of government for the participating states.

More about the origins of the OSCE and Switzerland’s role between the blocs:

More

50 years of the Helsinki Accords: Switzerland’s role between the blocs

What are the OSCE institutions?

On January 1, 1995, the participating states renamed the CSCE the OSCE. At the same time, they established a Secretariat, whose head is elected for a three-year term, and a Permanent Council with delegates in Vienna.

The OSCEExternal link also strengthened its institutional set-up. It established a Parliamentary Assembly made up of 323 parliamentarians with a secretariat in Copenhagen, Denmark, and an Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights based in Warsaw. Other key bodies include the Representative on Freedom of the Media in Vienna and the High Commissioner on National Minorities in The Hague.

Where does the OSCE work?

The bulk of the organisation’s staff and resources are deployed in field operations in southeastern Europe, eastern Europe, the Southern Caucasus and Central Asia. The mandates are agreed by the participating states on a consensual basis.

The OSCE is dedicated to resolving protracted conflicts in the region, for instance in Transnistria, the breakaway region of Moldova, and Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Together with the United Nations and the European Union, it co-chairs the Geneva International Discussions, launched after the brief but violent war between Russia and Georgia in August 2008.

From 2014 to 2022, the OSCE deployed a special monitoring mission in Ukraine. This came in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of conflict in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk between Ukrainian forces and Russian-backed separatists.

Is the OSCE in crisis?

Yes, the OSCE is undergoing an unprecedented crisis, according to many observers. Among them is security analyst Alexander Graef, who published a policy briefExternal link on the subject in March 2025.

In it Graef wrote: “Russia and Belarus have blatantly violated key norms of the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, severely undermining the OSCE’s role… While the OSCE cannot impose solutions, it remains a potentially vital platform for dialogue”.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is only one part of the story. Added to this is the obstructive behaviour of Russia and Belarus within the organisation.

Thus, key decisions such as the adoption of the budget, the extension of field missions and even the appointment of the chair country have been systematically undermined.

According to a studyExternal link published in Global Studies Quarterly, the OSCE is facing a legitimacy crisis that has brought it to the brink of irrelevance.

As causes for this, the study puts forward institutional weaknesses and diverging interests on the part of the participating states.

Former OSCE secretary general Thomas Greminger even concluded, in an opinion piece for Swissinfo, that “the OSCE plays no role in conflict management in Ukraine and has disappeared from the political radar of key Euro-Atlantic security players”.

More

What Switzerland can achieve with its 2026 OSCE chairship

How do the OSCE’s troubles fit into the wider global picture?

José Ángel López Jiménez, coordinator for international law and international relations at Comillas Pontifical University in Madrid, sees the challenges facing the OSCE in the broader context of “world structural disorder”.

The transition to a multipolar system has triggered a crisis of multilateralism and regionalism, which is impacting both the UN and regional players such as the OSCE. “This context has changed significantly since the OSCE came into being in 1995,” he says.

Although LópezExternal link has been critical of the OSCE in the past – for instance regarding Transnistria – he acknowledges that the organisation played a fundamental role in the conflict there, as well as in Nagorno-Karabakh and in South Ossetia, a separatist region of Georgia.

However, the organisation is increasingly reaching its limits. Similarly to the UN, whose main bodies, such as the Security Council, are often blocked, the OSCE is struggling to fulfil its mission in a consistent manner.

“This is not just a problem of the OSCE but a general failing of the international system, which can be traced back to the crisis of multilateralism and regionalism,” López laments.

More

Does the OSCE still have a purpose?

“Especially at a time like this, when new blocs are forming, it is vital that a forum of this kind continue to exist, and that it be used and made visible,” says Lucas RenaudExternal link, an expert on Swiss and Euro-Atlantic security at the Centre for Security Studies at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

López, meanwhile, highlights the OSCE’s work in the fields of border monitoring, the fight against human trafficking, counter-terrorism and the monitoring of ceasefire agreements. “There are very important aspects,” he says.

As for the security analyst Graef, he believes that determined political leadership and diplomacy are needed on multiple levels to break the deadlock. “The lessons learnt from the CSCE during the Cold War show that informal initiatives – especially by neutral states – can help to overcome blockages,” he says.

What can Switzerland do as OSCE chair in 2026?

Switzerland must make it clear that Russia has violated the principles of the Helsinki Final Act, Renaud says.

However, he advises against excluding Russia. Especially in times of crisis, war and polarisation, it is important to keep this negotiation channel open.

“What must not happen, though, is that Russia use the negotiations merely as a fig leaf for its stalling tactics, without having any real interest in results,” he adds.

And this even if “the differences are very great and the room for manoeuvre of an organisation like the OSCE is limited”.

Keeping “the difficult partner” in the OSCE is a wise tactic, López is convinced. He also points out that Russia only agreed to Switzerland assuming the chair in order “to break its own isolation from Western countries”.

López also mentions the United States, “the other partner”, which is aiming for the Nobel Peace Prize and wants to take credit for the results of all the OSCE’s work in Nagorno-Karabakh.

“For these reasons, it is crucial that the OSCE improve its communication and make its efforts more visible,” he adds. “Together with Switzerland, it should now use the stage of international Geneva to strengthen its capacity to act.”

The situation is dangerous, the specialist warns, and it reminds him of the interwar period. “Either we return to reason and to models of cooperation – or the Kantian ideal of an international society will be dashed.”

The Kantian ideal refers to the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s vision of a peaceful international order based on reason, law, and mutual respect; one where nations cooperate through shared principles rather than power or fear.

If that idea collapses, “then we all lose,” concludes López.

Edited by Marc Leutenegger/bvw. Adapted from German by Julia Bassam/ds

More

Our weekly newsletter on geopolitics

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.