Too hot to work? Extreme heat endangers billions of workers

From farms to factories, rising temperatures are cutting productivity and endangering lives, with the poorest paying the highest price.

Half the world is already struggling with the effects of extreme heat, according to a joint report from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) published on Friday. The collaborative guidance sets out recommendations for companies and governments as climate change – and heat stress in particular – upends the world of work.

“Extreme heat is a public health crisis,” said Rüdiger Krech, WHO director of environment, climate change and health, during a Thursday briefing. “It is already harming the health and livelihoods of billions of workers across the world.”

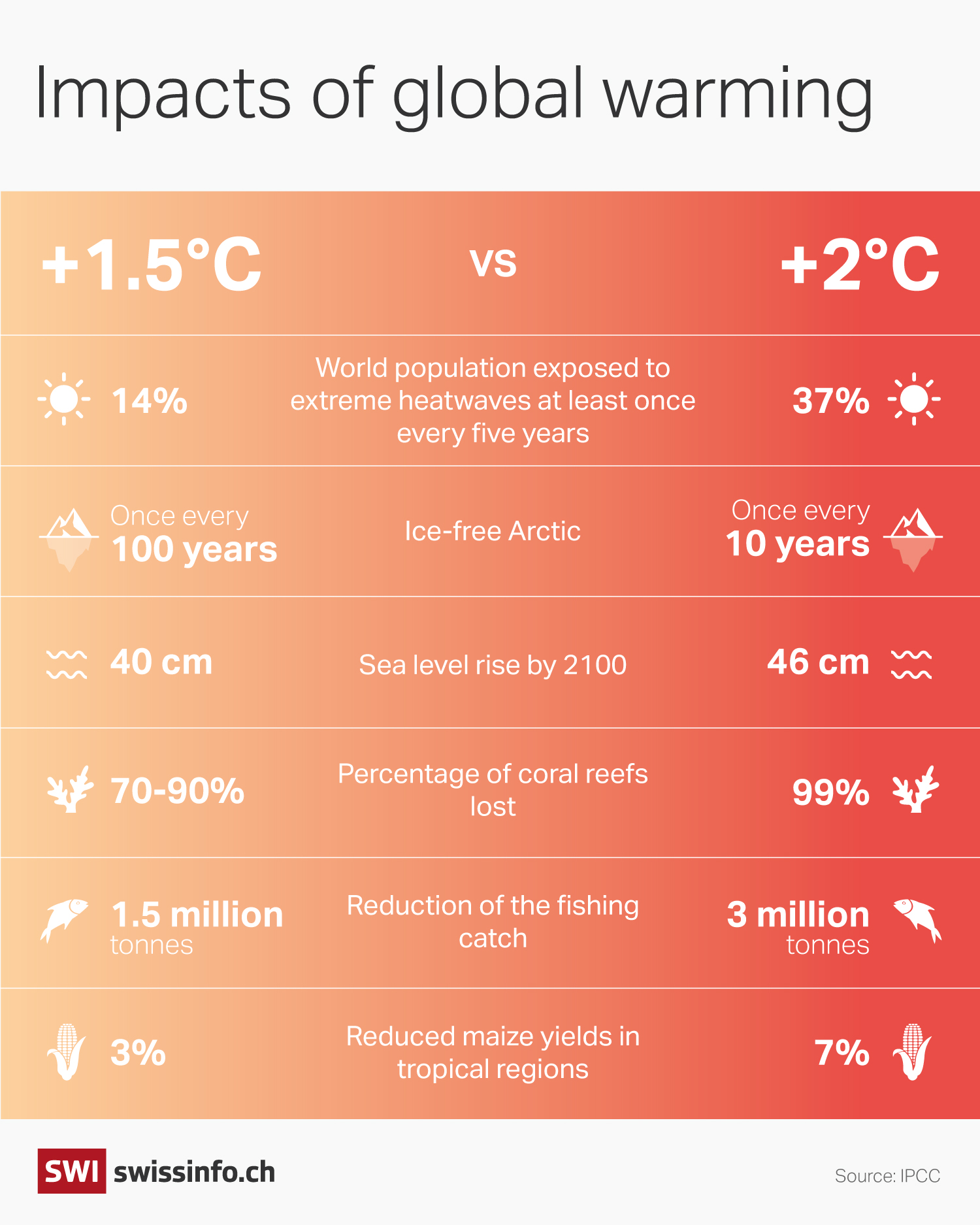

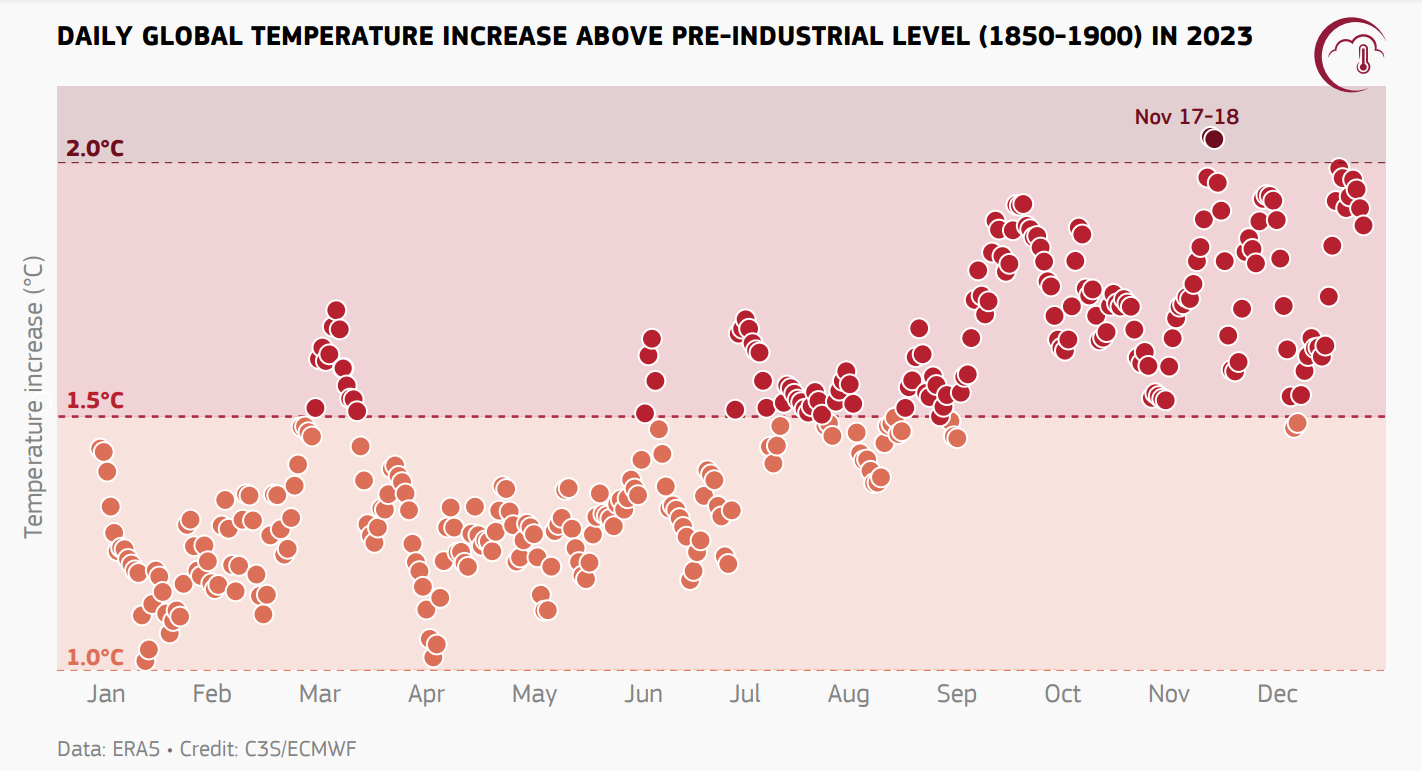

The warning comes as the WMO confirmed that 2024 was the warmest year on record, with global temperatures averaging 1.45°C above pre-industrial levels. The past decade has been the hottest in human history. The 2025 summer season saw temperatures regularly topping 50°C in the Middle East and 40°C across Europe, where southern countries once again battled devastating forest fires.

“Climate change implies that the health challenge associated with environmental heat stress will increase in intensity, and its direct as well as indirect negative effects will spread geographically,” the WMO-WHO guidance warned.

Workers on the front line

While heatwaves make headlines for spikes in hospitalisations and deaths, the more chronic threat plays out daily in the workplace. Millions of people in agriculture, construction and fishing must continue working in dangerous conditions, the report said.

The health consequences of heat stress are well documented: dehydration, kidney disease, neurological dysfunction and, in severe cases, death. Symptoms are frequently overlooked or misdiagnosed, delaying treatment. According to the report, those who frequently work in hot conditions suffer “additional physiological strain as well as an increased risk of ill health”.

Speaking at the same briefing, Joaquim Pintado Nunes, the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) head of occupational safety, underlined the scale of the problem. “Exposure to heat might be one of the most serious occupational hazards in today’s world of work,” he said, noting that more than 2.4 billion workers are exposed to excessive heat, which causes more than 22 million injuries and 19,000 fatalities per year.

Productivity losses measured in billions

The problem does not end with health. Productivity also drops as temperatures climb. The WHO-WMO guidance finds that “worker productivity decreases by 2-3% for every degree increase beyond 20°C in wet-bulb globe temperature”. This measure captures heat stress in direct sunlight, factoring in not just air temperature but also humidity, wind, sun angle and cloud cover.

The goal, Krech noted, is to keep workers’ core body temperature below 38°C. But experts speaking at the briefing declined to set a universal maximum safe temperature – a common request of labour unions, stressing that humidity, workload and local conditions create very different levels of risk.

The poor pay the highest price

The economic impact is another factor. In economies reliant on manual labour, the report warns that workplace heat stress “may affect not only individual livelihoods, but also family income and jeopardise the reduction of poverty”.

For wealthier populations, avoiding peak heat or moving work indoors may be possible. For low-income communities in developing countries, it is not. As the report notes, “avoiding heat exposure or reducing physical activity may lower health risks, but this is not compatible with the ability to live healthy and productive lives”.

+ Climate change puts Swiss tourism to the test

Workers are left facing a cruel trade-off: risk their health or risk their livelihood. That reality deepens inequality and threatens to reverse progress in poverty reduction. Short-term exposure to high diurnal temperatures increases the risk of premature death from cardiovascular causes, particularly among women and the elderly, the report said.

Not just shade and water

Governments in many countries now issue public heat-health warnings, but these are designed for the general population, not for those who must keep working regardless of conditions, according to the report.

“These approaches often have limited relevance for workers who must generally sustain some level of productivity to prevent the halt of economic activity,” the report noted.

The WHO and WMO instead call for tailored occupational heat action programmes, co-designed with employers, trade unions, workers and local authorities. Options include reorganising shifts, providing shaded rest breaks, offering protective clothing and deploying cooling technologies such as fans or wearable sensors.

In Africa, where much of the population works in the informal sector, experts say awareness raising is as important as national plans given the absence of formal protections.

Krech stressed that the challenge can no longer be dismissed as mere discomfort. “What is new is the severity,” he said. “Severity means not only more days of heat but also higher temperatures. When you see construction workers at 3pm in Madrid… that is something that needs to change.”

The report also highlights training gaps. “While the treatment for most of these conditions is well known, they are often misdiagnosed or go unrecognised, and this can have serious negative effects on patient health.”

A global development challenge

The guidance links heat stress directly to four UN Sustainable Development Goals: no poverty, good health, decent work and climate action. It argues that tackling the problem is not just about protecting workers on hot days, but about safeguarding entire economies and global supply chains.

Policies, it says, should be co-created with stakeholders and balance “practical feasibility, economic viability and environmental sustainability”. Without such action, both health and productivity costs will escalate as the planet continues to warm.

Nunes at the ILO was blunt, calling for bold, coordinated action: “Climate change is reshaping the world of work,” he said. “Action cannot wait.”

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.