New discovery excites Cern scientists

Scientists at Cern have reported potentially new and interesting effects using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world's most powerful particle accelerator.

Researchers at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (Cern) say the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) appears to have produced a small amount of the matter that existed in the first moments of the universe.

They said colliding particles seem to be creating “hot dense matter” that would have existed microseconds after the Big Bang and might hold the key for understanding how the liquids, gases and solids of our universe were created.

“We are all very excited and cautious,” Dave Barney, a scientist for the CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid) detector, told swissinfo.ch.

The CMS is one of six experiments around the 27-kilometre circular particle accelerator deep under the French-Swiss border near Geneva.

“It’s not one of the big scientific answers to things like the Higgs boson or super symmetry – but it’s new and not fully expected.”

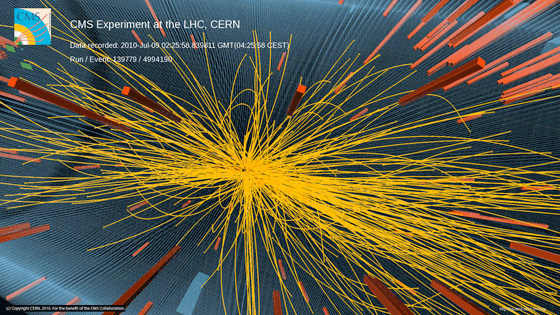

After almost six months of operation, the CMS is reported to have seen “potentially new and interesting effects” following a series of seven trillion electron volt (TeV) proton-proton collisions.

These tiny effects concern the paths taken by one hundred or more particles produced during collisions as they fly away from the point of impact.

Angular correlations emerged that showed that some of the particles are linked in a way not seen before in proton collisions, Cern reported. The phenomenon showed up as a “ridge-like structure” on computer graphs based on the data.

Talk to each other

“It’s significant as it could imply that an unknown mechanism exists in the collision dynamics,” CMS spokesman Guido Tonelli told swissinfo.ch.

He said that it was as if the particles talked to each other and decided which way to go.

There should be a dynamic mechanism somehow giving them a preferred direction, which is not down to the trivial explanation of momentum and energy conservation, Tonelli said, adding that this was something which was so far not fully understood.

A paper with their findings has been submitted to the wider scientific community for peer review, but Cern scientists underline the need for caution.

Tonelli said the CMS now needed more data to analyse fully what was going on.

“Starting to deliver”

The results are interesting as they mirror similar observations conducted at the United States Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, which have been interpreted as being possibly due to the creation of hot dense matter formed in the collisions.

“We are very excited,” said Raju Venugopalan, a senior Brookhaven scientist who wasn’t involved in Cern’s experiments. He told The Associated Press that the data showed “for the first time” that protons have quantum properties that can be enhanced in collisions.

Cern spokesman James Gillies said the experiments showed the LHC “is starting to deliver” after a patchy start that included costly repairs and upgrades.

“Up to now, we were remeasuring old physics,” he said. “Now we’re moving to new and better things.”

Even if the latest data fail to produce immediately useful knowledge, the tests show the collider’s unprecedented capacity for discovery, said Joe Incandela, a senior Cern scientist.

Atom smasher

In the LHC, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams are smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The experiments scour data from the collisions for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the so-called God particle, the yet-to-be-discovered Higgs boson.

Experts say the LHC is the largest scientific experiment in human history and could unlock many secrets of modern physics and answer questions about the universe and its origins.

In the LHC, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams are smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The beams usually move through two vacuum pipes, but at four points they collide in the hearts of the main experiments, known by their acronyms: ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb.

When operational, the detectors see up to 600 million collision events per second, with the experiments scouring the data for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the so-called God particle, the yet-to-be-discovered Higgs boson.

The $10 billion machine was launched with great fanfare on September 10, 2008, but broke down nine days later when a badly soldered electrical splice overheated, causing extensive damage to the massive magnets and other parts of the collider deep underground. It cost $40 million to repair and improve the machine so that it could be used again at the end of November.

Since then the collider has performed almost flawlessly, giving scientists valuable data and allowing it to quickly eclipse the next largest accelerator, the Tevatron at Fermilab near Chicago.

The plan is to replace simple protons with heavier lead nuclei for collisions in November. The LHC will be run continuously at 7 Tev for 18-24 months while steadily increasing the particle density in each beam until the end of 2011. It will then be shut down for a year of maintenance and upgrading to prepare it for years of experiments at full power – 14 TeV.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=a45b19f3)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.