Self-healing polymer generates army interest

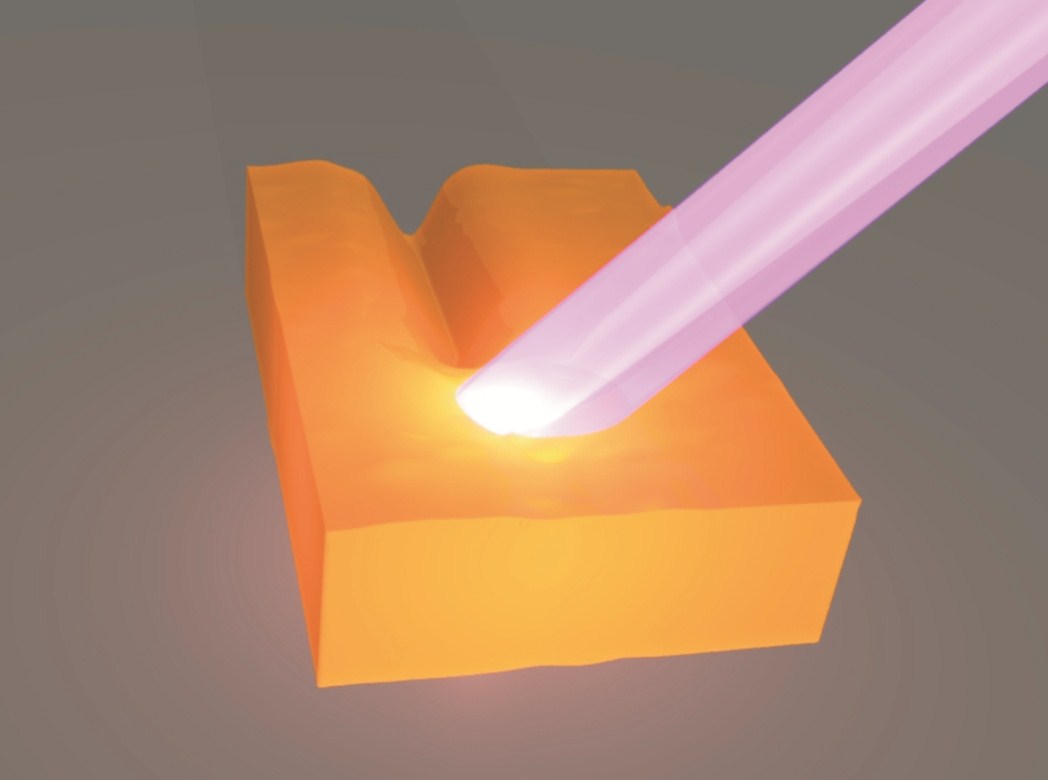

Imagine a scratched watch face or car door that can magically repair itself using ultraviolet light. This is not science fiction but the work of US-Swiss researchers.

Scientists from Fribourg University and two laboratories in the United States have developed a polymer-based coating, known as a “metallo-supramolecular” polymer, that can heal itself when placed under ultraviolet light for less than a minute.

“For the moment it’s still at the basic research level,” Christoph Weder, director of Fribourg University’s Adolphe Merkle Institute, told swissinfo.ch. “We are not looking to develop products for the market but concepts and tools that can then develop commercially viable materials. That’s the way our [nanoscience] institute functions.”

The findings by the teams from the Adolphe Merkle Institute, the Army Research Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, United States, and Case Western Reserve University in Ohio were published in a recent issue of Nature journal.

So what’s the US army’s interest in these new materials?

“I don’t want to speculate on their interest in supporting this particular project, but the people involved were really devoted to basic research,” said the Swiss professor of polymer chemistry and materials, who has worked for many years in the US.

The new material has potentially many different practical applications from tactile screens to other everyday consumer items like cars, floors and furniture that get easily scratched, as well as nail polish.

Plate of spaghetti

Plastics are traditionally made of polymers or molecules consisting of long chains of thousands of atoms, like a plate of spaghetti. When plastic is heated, it melts and can be moulded but this is a slow process due to the weight of the molecules and their entanglement.

A “metallo-supramolecular” polymer, on the other hand, is made of molecules that are about 25 times smaller and stuck together via metal ions. When the polymer is heated, they break up and as they are light the material flows much easier. When it cools the molecules stick back together at their metallic extremities and the material’s original properties are restored.

To do this there is no need to put your watch or mobile phone in the oven: a blast of intense ultraviolet light is sufficient.

“We used similar lamps to the ones found in dentists’ surgeries used to harden polymer fillings,” said Weder.

The amount of light needed is greater than normal sunlight so the new polymer remains stable outside and cannot melt on a sunny day.

Hot reaction

When a “metallo-supramolecular” polymer liquefies and fills the cracks and scratches, the material reaches temperatures of around 200 degrees Celsius. So even if the whole process takes less than a minute and the heat remains localised, there is a risk of getting burned.

The researchers are following up by analysing different metals that can serve as the glue between the molecules to see whether they have to reach the same temperatures to break the connections that hold the molecules together.

It still remains to be seen how thick the coating of the polymer needs to be to heal itself. For the moment, tests have been carried out on very thin layers.

“As we have been using ultra-violet light, the depth to which it can penetrate the material will always be a limiting factor. The light is not going to penetrate centimetres deep,” Weder said.

Nonetheless the researchers know that heat generated by ultraviolet light can travel deeper than normal light – but how far? This question still remains open.

Despite these constraints, the research has been well received in the science community.

“This is ingenious and transformative materials research,” said Andrew Lovinger, polymers program director at the US National Science Foundation’s Materials Research Division.

“It demonstrates the versatility and power of novel polymeric materials to address technological issues and serve society while creating broadly applicable scientific concepts.

Nanotech can be defined as research and technology developments at the atomic or molecular level, on a scale smaller than 100 nanometres – one ten-thousandth of a millimetre.

Particles and structures of this size differ from their counterparts in the microscopic world as relative surface area of these structures increases enormously and quantum effects occur. This can lead to changes in physical and chemical properties, often leading to improved characteristics e.g. water repellency.

Nanoscience and nanotechnology encompass a range of techniques rather than a single discipline and stretch across the scientific spectrum, touching on medicine, physics, engineering and chemistry.

While nanotechnology offers a glimpse of a whole array of new possibilities, there are also potential risks to consider.

In 2008 the federal government approved a plan of action on synthetic nanomaterials and a much-awaited follow-on report is due in November 2011. The overall aim is to set up a regulatory framework for nanotechnology.

The International Year of Chemistry 2011 (IYC 2011) is a worldwide celebration of the achievements of chemistry and its contributions to the well-being of humankind.

It has been organised by Unesco (the United Nations science agency) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Under the unifying theme “Chemistry – our life, our future”, IYC 2011 will offer a range of interactive, entertaining, and educational activities for all ages. The Year of Chemistry is intended to reach across the globe, with opportunities for public participation at the local, regional and national level.

(Source chemistry2011.org)

(Translated from French by Simon Bradley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=a45b19f3)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.